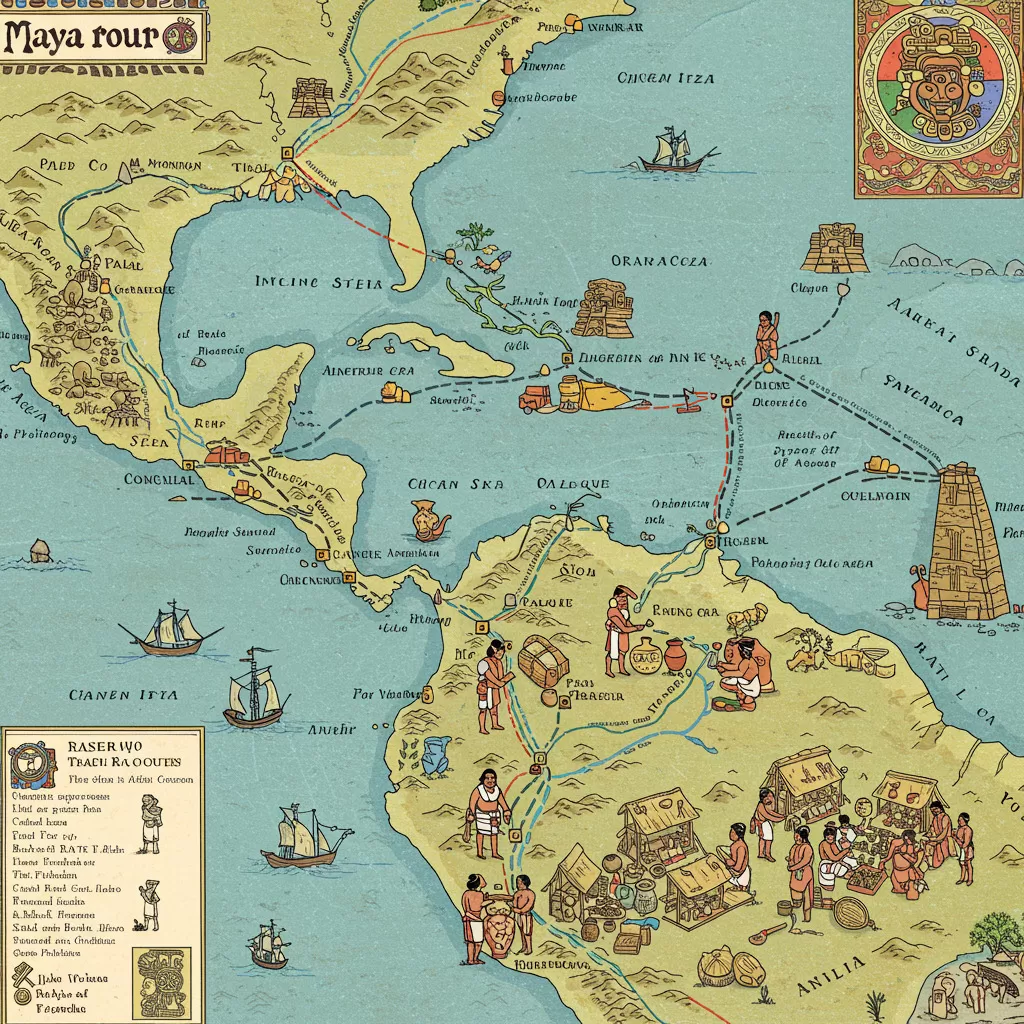

The Trade Routes of the Ancient Maya: Goods and Influence

The ancient Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in architecture, astronomy, and writing, was equally adept in the art of trade. Spanning the lush landscapes of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, the Maya established a complex network of trade routes that not only facilitated the exchange of goods but also fostered cultural interactions with neighboring societies. Understanding these trade routes provides valuable insights into the economic strategies and social dynamics that shaped the Maya world.

From the vibrant marketplaces of major cities to the bustling trade centers that dotted their territory, the Maya were skilled traders who exchanged a variety of goods, including precious materials such as jade and obsidian, agricultural products like cacao and maize, and beautifully crafted textiles. These exchanges were pivotal in building alliances and enhancing the socio-economic fabric of the civilization. As we delve deeper into the intricacies of the ancient Maya trade routes, we will uncover the profound impact these interactions had on their society, economy, and legacy.

Understanding the Ancient Maya Trade Routes

The ancient Maya civilization, which flourished in Mesoamerica from approximately 2000 BCE to the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, was a complex society characterized by its remarkable achievements in art, architecture, mathematics, and astronomy. However, one of the most significant aspects of the Maya civilization was its extensive trade networks that facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices across vast distances. Understanding the trade routes of the ancient Maya provides insight into their economy, social structure, and interactions with neighboring civilizations. This section delves into the geography of the Maya civilization and identifies key trade centers and cities that played a vital role in these networks.

Geography of the Maya Civilization

The Maya civilization occupied a diverse geographical area that included parts of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. This region is characterized by a variety of landscapes, including mountains, rainforests, and coastal plains, which influenced the development of trade routes. The geographic diversity provided access to a wide range of natural resources, which were crucial for trade. For instance, the highlands of Guatemala were rich in jade and obsidian, while the coastal regions offered access to marine resources.

The Maya region can be divided into three main geographical areas: the northern lowlands, the southern lowlands, and the highlands. The northern lowlands, primarily located in the Yucatán Peninsula, featured flat terrain and limestone bedrock. Major cities in this area, such as Chichén Itzá and Tulum, served as vital trade hubs due to their strategic locations along coastal trade routes. The southern lowlands, encompassing parts of Guatemala and Belize, were characterized by dense jungles and mountainous regions. This area was home to significant cities like Tikal and Calakmul, which were major centers of commerce and culture.

The highlands, particularly in the Guatemalan region, were known for their agricultural productivity, especially in the cultivation of maize, beans, and cacao. The varied geography not only influenced agricultural practices but also determined trade routes, which were often dictated by the natural landscape. Rivers, mountain passes, and coastal access points played essential roles in facilitating trade, as they allowed for the movement of goods and people across the region.

Key Trade Centers and Cities

The ancient Maya civilization had numerous trade centers and cities that emerged as focal points for commerce, culture, and political power. These cities were often strategically located at the crossroads of major trade routes, enabling them to control and benefit from the exchange of goods. Some of the most prominent trade centers include:

- Tikal: Located in the northern lowlands of Guatemala, Tikal was one of the most powerful and influential Maya city-states. It served as a central hub for trade and was known for its impressive architecture and large population. Tikal's strategic location allowed it to control trade routes connecting the highlands and lowlands, facilitating the exchange of goods such as jade, obsidian, and agricultural products.

- Calakmul: Another significant city-state located near the modern border of Mexico and Guatemala, Calakmul was a major rival of Tikal. Its location in the rainforest allowed it to access valuable resources and control trade routes. Calakmul was also known for its political power and cultural influence, contributing to the broader Maya trade network.

- Chichén Itzá: This northern lowland city became a prominent trade center during the Postclassic period. Chichén Itzá was strategically located near cenotes (natural sinkholes) that provided water, making it an ideal stop for traders. The city was known for its architectural marvels, including the iconic El Castillo pyramid, and served as a melting pot of various cultural influences.

- Palenque: Nestled in the Chiapas region, Palenque was a significant city known for its stunning architecture and inscriptions. It served as a vital trade center, connecting the lowlands with the highlands and facilitating the exchange of goods, particularly textiles and ceramics.

- Tulum: Located on the coast of the Caribbean Sea, Tulum was an important trading port that facilitated maritime trade. Its strategic position allowed for the exchange of goods with other coastal cultures, such as the Totonacs and the Aztecs, making it a key player in the broader trade networks of Mesoamerica.

The trade routes connecting these cities were not only vital for the exchange of goods but also served as conduits for cultural interaction and the dissemination of ideas. The Maya engaged in extensive trade with neighboring civilizations, such as the Olmecs, Teotihuacan, and later the Aztecs, creating a complex web of economic and social relationships.

The Maya trade routes were characterized by both overland and maritime pathways. Overland routes often followed established trails that traversed the diverse landscapes of the region, while maritime routes connected coastal cities with trade partners across the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. The use of canoes and smaller boats was prevalent for transporting goods along rivers and coastal waters, enabling the Maya to exploit the rich resources of their environment.

In addition to the exchange of material goods, these trade routes facilitated cultural and technological exchanges. The movement of people along these routes led to the sharing of knowledge, artistic styles, and religious practices, further enriching Maya society. For instance, the introduction of new agricultural practices and crops, such as cacao, had a lasting impact on Maya culture and economy.

The complexity of Maya trade routes is evident in the archaeological record, where remnants of trade goods, such as pottery, tools, and luxury items, have been found far from their origin points. This suggests that goods were often traded multiple times before reaching their final destination, highlighting the intricate nature of Maya commerce.

In summary, understanding the geography of the Maya civilization and its key trade centers provides valuable insight into the ancient Maya trade routes. The diverse landscapes, strategic city locations, and extensive trade networks were crucial for the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices that defined the Maya civilization. The legacy of these trade routes continues to be felt today, as modern scholars and archaeologists work to uncover the rich history of this remarkable culture.

Goods Traded by the Ancient Maya

The ancient Maya civilization, known for its impressive achievements in architecture, mathematics, and astronomy, was also a sophisticated society engaged in extensive trade. The exchange of goods was not only crucial for their economy but also served as a means to facilitate cultural interactions and the spread of ideas. This section delves into the myriad goods traded by the ancient Maya, with a focus on precious materials, agricultural products, and textiles and crafts. Each category highlights the significance of these goods in the daily lives of the Maya and their influence on neighboring cultures.

Precious Materials: Jade and Obsidian

Among the most coveted trade goods in the Maya civilization were precious materials, particularly jade and obsidian. These materials held not only intrinsic value but also cultural and spiritual significance.

Jade, often referred to as "the stone of heaven," was highly valued for its beauty and rarity. It was used to create a variety of items, including jewelry, ceremonial masks, and other decorative objects. The Maya believed jade possessed magical properties, associating it with life, fertility, and the underworld. The trade of jade was concentrated in specific regions, notably in the Motagua Valley of present-day Guatemala, where the highest quality jade was sourced. The demand for jade extended beyond the Maya region, with artifacts discovered in distant archaeological sites indicating that jade was traded as far as Mesoamerica, highlighting its importance in inter-regional trade networks.

Obsidian, a volcanic glass, was another crucial material in the Maya trade. It was primarily used to manufacture tools and weapons due to its sharp edges and durability. The Maya sourced obsidian from several volcanic regions, with the most notable being the highlands of Guatemala and the Tehuacán Valley in Mexico. The trade of obsidian played a vital role in the Maya economy, as it was not only an essential material for everyday life but also a valuable commodity in trade with neighboring cultures. Obsidian tools and artifacts have been found throughout Mesoamerica, indicating extensive trade routes and interactions among various civilizations.

Agricultural Products: Cacao and Maize

The agricultural products traded by the ancient Maya were fundamental to their sustenance and economy. Among these, cacao and maize stood out as essential staples that not only fed the population but also played vital roles in rituals and trade.

Cacao, native to the tropical regions of Central America, was highly prized by the ancient Maya, who cultivated it on a large scale. The Maya prepared a bitter beverage from cacao beans, often flavored with spices and consumed during religious ceremonies and social gatherings. Cacao was so valuable that it was used as a form of currency, facilitating trade between communities. The remarkable value of cacao is evidenced by its frequent depiction in Maya art and inscriptions, highlighting its importance in their society. The trade of cacao extended beyond the Maya, influencing other Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Aztecs, who also adopted its use as currency and in rituals.

Maize, or corn, was the cornerstone of the Maya diet and culture. It was not only a staple food source but also held deep spiritual significance. The Maya believed that humans were created from maize, which further underscored its importance. The cultivation of maize allowed for surplus production, enabling the Maya to engage in trade with neighboring communities. Maize was traded in various forms, including whole kernels, ground flour, and prepared dishes such as tortillas and tamales. The trade routes established for maize facilitated cultural exchange, as the Maya interacted with other civilizations through the sharing of agricultural practices and culinary traditions.

Textiles and Crafts

The Maya were skilled artisans, producing intricate textiles and crafts that were highly sought after in trade. Their textiles were made from cotton and other natural fibers, adorned with vibrant dyes and elaborate patterns. These textiles served multiple purposes, including clothing, ceremonial garments, and trade goods.

Textiles played a significant role in Maya society, as they were often used to signify social status and identity. Wealthy individuals wore finely woven garments, while lower-class citizens typically wore simpler clothing. The production of textiles was a labor-intensive process, involving spinning, dyeing, and weaving. Women primarily undertook this work, which was integral to their economic contributions within the household and community. The trade of textiles facilitated not only the exchange of goods but also cultural interactions, as designs and techniques were shared among different groups.

Additionally, the Maya produced a variety of crafts, including pottery, stone carvings, and wooden artifacts. These crafts were often imbued with cultural significance, reflecting the beliefs and values of the society. Pottery, for instance, was essential for storage, cooking, and serving food. The intricate designs and motifs found on Maya pottery often depicted scenes from mythology, daily life, and rituals, making them valuable both for their functionality and artistic merit. The trade of these crafts not only provided economic benefits but also contributed to the cultural exchange between the Maya and neighboring civilizations, as artisans shared techniques and styles.

Conclusion

The trade of goods by the ancient Maya played a pivotal role in shaping their civilization and its interactions with neighboring cultures. The exchange of precious materials such as jade and obsidian, alongside agricultural products like cacao and maize, and the craftsmanship of textiles and other artifacts, facilitated economic prosperity and cultural enrichment. The legacy of these trade practices continues to influence modern perceptions of the Maya, showcasing their ingenuity and the complexity of their societal structures.

As we explore the ancient trade routes of the Maya, it becomes evident that their economic practices were deeply intertwined with their cultural identity, establishing a rich tapestry of interactions that shaped the course of history in Mesoamerica.

Cultural and Economic Influence of Trade

The ancient Maya civilization was remarkable not only for its achievements in architecture and astronomy but also for its extensive trade networks that spanned Mesoamerica. These trade routes facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices, profoundly impacting the social and economic fabric of Maya society. Understanding the cultural and economic influence of trade involves examining interactions with neighboring civilizations, the impact on Maya society and economy, and the legacy of Maya trade in modern times.

Interactions with Neighboring Civilizations

The Maya civilization thrived in a region that was home to various other cultures, including the Olmecs, Teotihuacan, and later the Toltecs and Aztecs. The interactions through trade were not merely economic transactions; they were cultural exchanges that shaped the Maya worldview. Trade allowed the Maya to acquire goods that were not locally available, such as obsidian from the highlands of Guatemala and jade from the Motagua Valley. In return, they exported local products like cacao and textiles, influencing the economies and cultures of their trading partners.

Trade routes extended far beyond the immediate neighboring regions. For instance, the Maya traded with the Gulf Coast cultures, exchanging goods such as fish and salt for luxury items. The exchange of goods often included the movement of people, ideas, and religious practices. The spread of the Mesoamerican ballgame, which originated in the Olmec culture, can be attributed to trade connections and is a prime example of how cultural elements were disseminated through economic relationships.

Moreover, the Maya engaged in diplomatic relations through trade which often included marriages and alliances. Such interactions were vital for establishing peace and collaboration among different city-states. The presence of Maya artifacts in distant lands, such as the Olmec and Teotihuacan, suggests the extent of trade networks and the cultural exchanges that resulted from these interactions.

Impact on Maya Society and Economy

Trade played a pivotal role in shaping the Maya economy and social structure. The wealth generated from trade contributed to the development of powerful city-states, which were often governed by elite ruling classes. The accumulation of wealth allowed for the construction of monumental architecture, including temples and palaces, which served as symbols of power and religious significance.

In economic terms, the Maya's reliance on trade created a complex system of exchange that included barter and the use of cacao beans as a form of currency. This system facilitated not only local trade but also long-distance commerce, allowing the Maya to engage in extensive networks that connected them to other Mesoamerican cultures. The Maya traded goods such as textiles, ceramics, and tools, which were essential for daily life and served as valuable trade items.

Additionally, agriculture played a crucial role in the Maya economy. The production of staple crops like maize, beans, and squash supported trade, as surplus agricultural products were often exchanged for goods and services. The relationship between agriculture and trade was symbiotic; as trade increased, so did agricultural production, leading to population growth and the expansion of cities. This growth often resulted in social stratification, with a clear divide between the elite classes who controlled trade and resources and the common populace who relied on agricultural labor.

Furthermore, the impact of trade on Maya society can be seen in the social hierarchy that developed. The elite, who controlled trade routes and wealth, often dictated cultural practices, religious beliefs, and even political decisions. This centralization of power due to trade had long-lasting effects on the governance of Maya city-states, leading to conflicts over trade routes and resources.

Legacy of Maya Trade in Modern Times

The legacy of ancient Maya trade extends into modern times in various ways, influencing contemporary societies and cultures. The Maya's sophisticated trade networks and their ability to adapt to changing economic conditions serve as a model for understanding trade dynamics in today's world. Scholars and archaeologists continue to study ancient trade routes, revealing new insights into how the Maya interacted with their environment and with each other.

In modern Mesoamerica, the remnants of ancient trade routes can still be traced, influencing current socio-economic practices. Many communities still engage in barter systems reminiscent of ancient trade practices, highlighting the ongoing relevance of these historical trade networks. The cultural exchanges initiated by the ancient Maya continue to resonate in the culinary traditions, art, and even language of modern Mesoamerican societies.

Furthermore, the understanding of ancient trade networks has implications for modern economic development. By studying how the Maya navigated trade challenges, contemporary societies can glean lessons on resource management, sustainability, and the importance of cultural exchange in fostering economic growth. The values of cooperation and mutual benefit that characterized ancient Maya trade are still relevant today in efforts to promote fair trade and sustainable practices.

In summary, the cultural and economic influence of trade among the ancient Maya is a complex tapestry woven from interactions with neighboring civilizations, the profound impacts on Maya society and economy, and the enduring legacy that continues to shape modern Mesoamerican cultures. The ancient Maya's ability to navigate trade routes and establish connections across vast distances speaks to their ingenuity and adaptability, serving as an enduring testament to their civilization's richness and complexity.