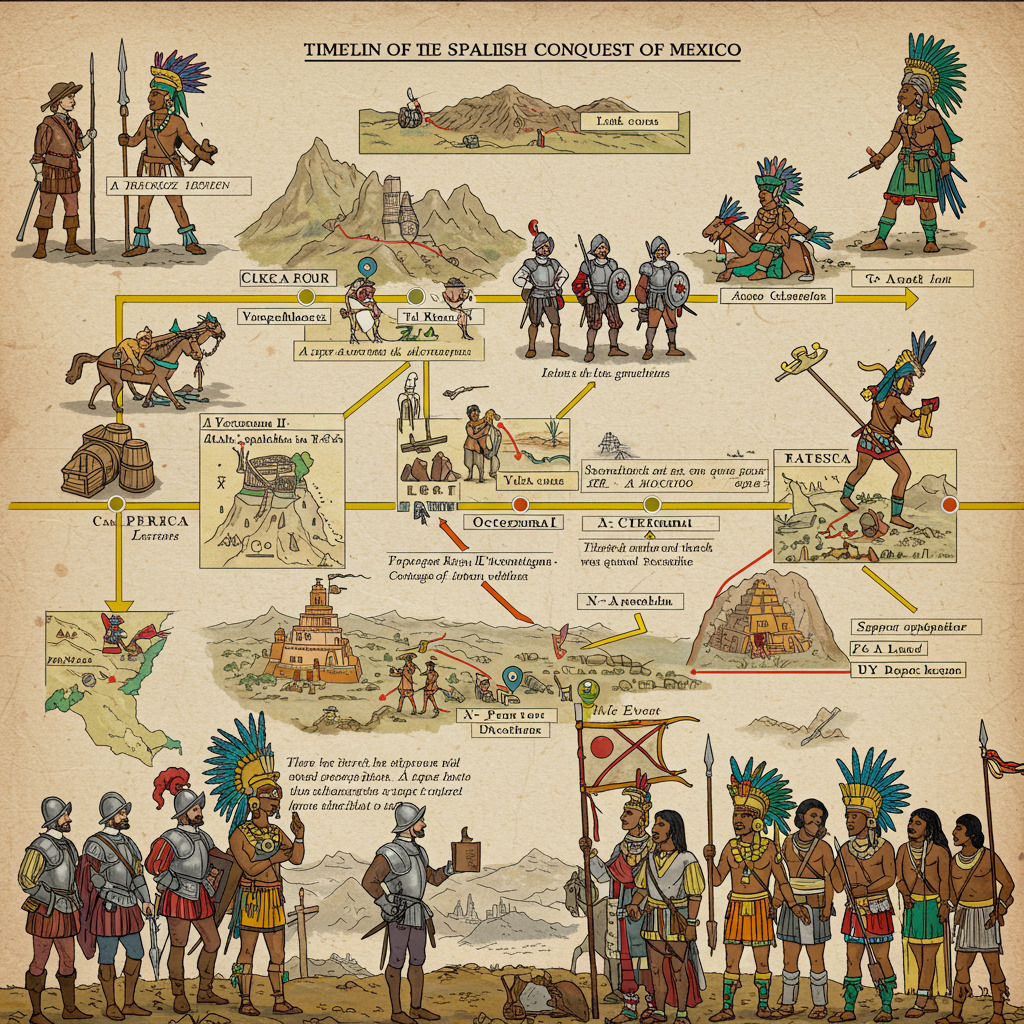

The Timeline of the Spanish Conquest of Mexico: Key Events

The history of Mexico is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of ancient civilizations, cultural exchanges, and pivotal moments that have shaped the nation. Among these moments, the Spanish Conquest stands out as a defining chapter that not only altered the course of Mexican history but also left an indelible mark on the identity of the region. This article delves into the timeline of the Spanish Conquest, highlighting key events that illustrate the dramatic encounters between Spanish explorers and the indigenous peoples of Mexico.

Beginning with the backdrop of Spanish exploration, we will explore how the arrival of Hernán Cortés and his forces set the stage for a series of events that would ultimately lead to the fall of one of the most powerful indigenous empires in the Americas. Through strategic alliances and intense conflicts, the Spanish conquest reshaped the social, political, and cultural landscapes of Mexico, paving the way for a new era characterized by complex interactions between the old and new worlds.

As we examine the consequences and legacy of this monumental event, we will uncover the profound implications for indigenous populations and the long-lasting effects on Mexico's development. Join us on this journey through time as we unravel the significant moments that defined the Spanish Conquest of Mexico and continue to resonate in its history today.

The Prelude to the Spanish Conquest of Mexico

The Spanish conquest of Mexico, a monumental event in world history, did not occur in isolation. It was preceded by a complex interplay of exploration, ambition, and the rise of powerful indigenous civilizations. Understanding the background of Spanish exploration and the indigenous societies that existed prior to the arrival of Hernán Cortés is crucial in grasping the factors that led to the eventual conquest. This section delves into the motivations behind Spanish exploration and the richness of indigenous cultures in Mexico before the onset of European colonization.

Background of Spanish Exploration

The narrative of Spanish exploration begins in the late 15th century, a time marked by significant changes in Europe. The Reconquista, the centuries-long campaign to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula from Islamic rule, culminated in 1492 with the fall of Granada. This victory imbued Spain with a sense of religious and nationalistic fervor, prompting its rulers, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, to seek new territories beyond Europe. The lure of wealth, resources, and the spread of Christianity became the driving forces behind exploration.

Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492, sponsored by the Spanish Crown, is often viewed as the catalyst for the Age of Discovery. Although Columbus did not reach the mainland of North America, his expeditions opened the floodgates for further exploration. Following Columbus, explorers such as Juan Ponce de León, Hernán Cortés, and Francisco Pizarro embarked on journeys that would lead to the conquest of vast territories in the Americas.

In the context of Mexico, Hernán Cortés emerged as a key figure. Born in 1485 in Medellín, Spain, Cortés was a man of ambition and determination. After studying law in Salamanca, he set sail for the New World in 1504. By the time he arrived in Mexico in 1519, he had already gained experience in the Caribbean and had developed a keen understanding of the dynamics of power and wealth in the regions he encountered.

The Spanish Crown was eager to capitalize on the potential riches of the New World, particularly in gold and silver. Reports from earlier expeditions had hinted at the existence of wealthy civilizations in Mexico, fueling the ambitions of explorers like Cortés. The Spanish were not only driven by economic interests but also by a desire to spread Christianity, reflecting the intertwining of commerce and faith in their imperial endeavors.

Indigenous Civilizations Before Conquest

Before the arrival of the Spanish, Mexico was home to a multitude of indigenous civilizations, each with its own rich history, culture, and social structure. Among the most prominent were the Aztecs, Maya, and various other tribes that populated the region. Understanding these civilizations provides insight into the complexities that the Spanish faced upon their arrival.

The Aztec Empire, which rose to prominence in the 14th century, was one of the most advanced and powerful indigenous civilizations in Mesoamerica. Centered in the Valley of Mexico, the Aztecs established their capital at Tenochtitlan, which is modern-day Mexico City. The city was renowned for its impressive architecture, including temples, canals, and marketplaces, showcasing a sophisticated urban planning system.

Economically, the Aztecs thrived on agriculture, trade, and tribute from subjugated tribes. They developed a complex social hierarchy, with the emperor at the top, followed by nobles, priests, warriors, merchants, and commoners. Religion played a central role in Aztec society, with a pantheon of gods and elaborate rituals, including human sacrifices that were believed to appease the deities and ensure the continuation of the world.

In addition to the Aztecs, the Maya civilization, located primarily in the Yucatán Peninsula, also flourished before Spanish arrival. Known for their advancements in mathematics, astronomy, and writing, the Maya developed a complex calendar system and monumental architecture, including the famous pyramids at Chichen Itza and Tikal. The Maya civilization was characterized by city-states that engaged in trade, warfare, and cultural exchanges, yet they never unified under a single empire like the Aztecs.

Other notable indigenous groups included the Mixtecs and Zapotecs, who inhabited regions in Oaxaca, and the Tarascans in Michoacán. Each of these civilizations contributed to the rich tapestry of Mesoamerican culture, with unique languages, traditions, and artistic expressions. The diversity among these groups created a dynamic and multifaceted pre-Columbian society, which would soon face the overwhelming force of Spanish colonization.

As the Spanish approached the shores of Mexico, they encountered not only a land rich in resources but also complex societies with established political structures, trade networks, and cultural practices. The indigenous peoples were not merely passive victims; they had their own histories, struggles, and alliances. This context is vital to understanding the eventual interactions between the Spanish and the indigenous populations during the conquest.

The arrival of Hernán Cortés marked a turning point in the history of Mexico, as he initiated a series of events that would irrevocably change the course of the region's history. The prelude to the conquest was characterized by a mix of ambition, exploration, and the confrontation of two vastly different worlds, each with its own aspirations and challenges.

In summary, the background of Spanish exploration and the indigenous civilizations present in Mexico before the conquest are crucial to comprehending the dynamics that unfolded during the Spanish conquest. The motivations of the Spanish and the richness of indigenous cultures set the stage for one of the most significant encounters in history, leading to profound transformations in Mexico's social, political, and cultural landscape.

Key Events of the Spanish Conquest

The Spanish Conquest of Mexico is one of the most significant and transformative events in world history. It marked the beginning of European colonial dominance in the Americas, leading to profound changes in indigenous cultures, economies, and societies. The conquest was a complex process involving numerous key events that unfolded between the early 16th century and the fall of the Aztec Empire. This section aims to explore these pivotal moments, focusing on Hernán Cortés's arrival in Mexico, the establishment of alliances with indigenous tribes, and the ultimate fall of Tenochtitlan.

Hernán Cortés's Arrival in Mexico

In 1519, Hernán Cortés, a Spanish conquistador, arrived on the shores of what is now Mexico. This marked the beginning of a significant expedition that would lead to the downfall of one of the most powerful indigenous empires in the Americas: the Aztec Empire. Cortés had initially been part of an expedition to Cuba, but he was driven by an insatiable thirst for wealth and glory. He set sail from Cuba with a small fleet of ships, approximately 600 men, and a handful of horses, aiming to explore the mainland and capitalize on the rumored riches of the Aztecs.

Cortés's arrival was not just a chance encounter; it was a calculated move inspired by the tales of extraordinary wealth and sophisticated civilizations that had spread among the Spanish explorers. Upon landing in Veracruz, Cortés quickly established himself as a formidable leader. He recognized the importance of alliances and diplomacy, which would later play a crucial role in his success. This initial foothold at Veracruz provided Cortés with the opportunity to gather information about the Aztecs and their empire from various indigenous groups he encountered.

As Cortés ventured inland, he captured the city of Cempoala and allied with the Totonac people, who were eager to overthrow Aztec rule. This alliance not only bolstered his forces but also provided him with vital intelligence about the Aztec Empire and its capital, Tenochtitlan. The strategic importance of establishing alliances with local tribes became apparent, as these alliances would form the backbone of Cortés’s military campaign against the Aztecs.

The Establishment of Alliances with Indigenous Tribes

Recognizing the strength of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés sought to build alliances with indigenous tribes that were subjugated under Aztec rule. This strategy proved to be a game-changer in the conquest of Mexico. Cortés’s ability to forge alliances was not merely opportunistic; it was a well-thought-out tactic based on the political dynamics of the region.

One of the most significant alliances was with the Tlaxcala people, who had been longstanding enemies of the Aztecs. The Tlaxcalans, motivated by their desire for independence and revenge against the Aztec overlords, provided Cortés with a substantial force of warriors. In a series of battles known as the "Siege of Tlaxcala," Cortés demonstrated military prowess that further solidified his reputation as a formidable leader. With the Tlaxcalans by his side, Cortés was able to march toward Tenochtitlan with an army that had grown to several thousand warriors.

Another critical alliance was formed with the Xochimilco, who also opposed Aztec rule. Through these alliances, Cortés was able to gather a diverse coalition of indigenous peoples, each with their own grievances against the Aztecs. The unity among these tribes, fueled by a common enemy, significantly enhanced Cortés's military capabilities. The psychological impact of this coalition was profound, as it demonstrated to the Aztecs that their dominance was being challenged from within.

The establishment of these alliances also had cultural implications. As Spanish and indigenous troops marched together, they began to share knowledge, technology, and even tactics. The indigenous allies contributed local knowledge about the terrain and the Aztec military strategies, which proved invaluable in the face of the well-trained Aztec warriors. However, this collaboration was not without tensions, as differing cultural practices and worldviews sometimes clashed. Nevertheless, the alliances were a testament to the dynamics of power in pre-colonial Mexico, where shifting loyalties could alter the fate of entire empires.

The Fall of Tenochtitlan

The culmination of Cortés's campaign against the Aztec Empire was the dramatic siege and fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521. The city, which was a marvel of engineering and a cultural center, was built on a series of islands in Lake Texcoco and was connected to the mainland by causeways. As Cortés approached Tenochtitlan, he faced a formidable challenge. The Aztecs, led by Emperor Moctezuma II, were not only prepared for battle but also believed that Cortés might be a returning god, Quetzalcoatl, fulfilling a prophecy.

Upon entering the city, Cortés initially received a warm welcome from Moctezuma and the Aztecs. However, tensions quickly escalated, leading to violence. In 1520, after a series of skirmishes and misunderstandings, Cortés's forces were forced to retreat during what is known as "La Noche Triste" or "The Sad Night." This retreat resulted in significant casualties and a temporary setback for the Spanish. However, this defeat was not the end of Cortés's ambitions. He regrouped, reinforced his ranks with additional indigenous allies, and devised a plan to besiege Tenochtitlan.

The siege began in 1521 and lasted several months, during which the Spanish and their allies cut off supplies and reinforcements to the city. The Aztec defenses were formidable, but they were ultimately overwhelmed by the combination of Spanish weaponry, tactics, and the sheer number of indigenous allies who turned against the Aztecs. The siege resulted in widespread devastation, as starvation and disease ravaged the population of Tenochtitlan. The Spanish employed a strategy of psychological warfare, using their horses and artillery to instill fear within the Aztec ranks.

On August 13, 1521, Tenochtitlan finally fell to Cortés. The city was left in ruins, its stunning temples and palaces destroyed. The fall of Tenochtitlan not only marked the end of the Aztec Empire but also signified the beginning of a new era in Mexico. The Spanish established Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan, which would become the center of colonial power in the Americas.

Key Takeaways

- Cortés's arrival in Mexico initiated a campaign fueled by ambition and strategic alliances.

- Alliances with indigenous tribes like the Tlaxcalans were crucial for the Spanish conquest.

- The fall of Tenochtitlan marked the end of the Aztec Empire and the establishment of Spanish dominance in the region.

- The conquest led to significant cultural exchange, conflict, and the reshaping of Mexican society.

The events that unfolded during the Spanish conquest were not isolated incidents; they were interconnected moments in a larger narrative of colonization, cultural transformation, and conflict. The rise and fall of Tenochtitlan serve as powerful reminders of the complexities of history, where the interplay of power, ambition, and resistance shaped the fate of entire civilizations. Understanding these key events allows for a deeper comprehension of the consequences of the Spanish conquest, which have left an indelible mark on the history of Mexico and the Americas.

Consequences and Legacy of the Conquest

The Spanish conquest of Mexico, led by Hernán Cortés and his men, marked a pivotal moment in history that reshaped the cultural, social, and political landscape of the Americas. The aftermath of this monumental event not only altered the fate of indigenous civilizations but also set the stage for a complex interplay of cultures that would define Mexico for centuries to come. In this section, we will explore the consequences of the conquest, particularly focusing on cultural exchange and syncretism, the impact on indigenous populations, and the long-term effects on Mexico's development.

Cultural Exchange and Syncretism

The Spanish conquest initiated a profound cultural exchange that brought together European and indigenous traditions, beliefs, and practices. This syncretism was reflected in various aspects of life, including religion, language, art, and cuisine.

One of the most significant areas of cultural exchange was religion. The Spanish aimed to convert the indigenous populations to Christianity, often building churches atop ancient temples. This led to a blending of Catholic and indigenous beliefs, resulting in unique religious practices. For instance, many indigenous people adopted Christian saints, integrating them with their traditional deities. The Virgin of Guadalupe emerged as a powerful symbol of this syncretism, representing a fusion of the Spanish Virgin Mary and the indigenous goddess Tonantzin. Today, she stands as a national symbol of Mexico, embodying both the colonial past and the indigenous heritage.

Language also underwent significant changes due to the conquest. While Spanish became the dominant language, many indigenous languages persisted, and some words from these languages made their way into Spanish. For example, words like "chocolate," "tomato," and "coyote" have indigenous roots and are now integral to the Spanish language and culture. This linguistic exchange reflects the blending of cultures and the adaptation of new ideas and practices.

Art and architecture also saw a significant transformation during this period. The Spanish introduced European artistic styles, which merged with indigenous techniques and themes. Churches and cathedrals built during the colonial period often feature a mix of Gothic and Mesoamerican designs, demonstrating this fusion. The use of vibrant colors and intricate patterns in textiles and pottery also reflects the blending of artistic traditions. This unique artistic expression continues to influence contemporary Mexican art, showcasing the enduring legacy of the conquest.

Impact on Indigenous Populations

The conquest had devastating effects on indigenous populations, leading to significant demographic, social, and economic changes. The introduction of new diseases, such as smallpox, measles, and influenza, had catastrophic consequences. Indigenous communities, lacking immunity to these foreign illnesses, faced dramatic population declines. It is estimated that within the first century of Spanish colonization, Mexico's indigenous population decreased by as much as 90%. This demographic collapse resulted in the loss of entire communities and cultures, altering the fabric of Mexican society.

In addition to disease, the Spanish imposed harsh labor systems on the indigenous people, such as the encomienda system. This system granted Spanish settlers the right to extract tribute and labor from indigenous communities in exchange for protection and religious instruction. However, in practice, it often resulted in exploitation and abuse, further decimating indigenous populations. The forced labor in mines and plantations led to severe working conditions and high mortality rates among the indigenous workers.

Social structures within indigenous communities were also disrupted. The conquest dismantled traditional governance systems and replaced them with Spanish colonial administration. Indigenous leaders often faced marginalization, and their authority was undermined, leading to a loss of autonomy. This disruption has had lasting effects, as many indigenous groups continue to struggle for recognition and rights within modern Mexico.

Despite these challenges, indigenous groups displayed resilience and adaptability. Many communities found ways to resist Spanish oppression and maintained aspects of their cultural identity. Revolts and uprisings, such as the Mixtón War and the Pueblo Revolt, exemplify the resistance against Spanish rule. Additionally, various indigenous languages, customs, and traditions have persisted, contributing to the rich cultural mosaic of contemporary Mexico.

Long-term Effects on Mexico's Development

The legacy of the Spanish conquest has had profound long-term effects on Mexico's development, shaping its political, economic, and social landscape. The establishment of a colonial system created a new social hierarchy, often privileging Spanish settlers and their descendants over indigenous populations. This hierarchy has persisted in various forms, contributing to ongoing social inequalities in modern Mexico.

The economic structures established during the colonial period laid the foundation for Mexico's future development. The Spanish focused on extracting resources, particularly silver, which became a vital part of the colonial economy. The mines in Zacatecas and Guanajuato became significant sources of wealth for Spain and catalyzed economic growth. However, this extraction often came at the expense of indigenous labor and resources, leading to a legacy of exploitation that continues to resonate in contemporary economic disparities.

Politically, the conquest resulted in the establishment of a centralized colonial government that would influence Mexico's governance for centuries. The Spanish crown exerted control over the territory, leading to the creation of viceroyalties and a bureaucratic system that prioritized Spanish interests. This legacy of centralized governance has impacted Mexico's political evolution, shaping its struggles for independence and the development of its national identity.

The fight for independence in the early 19th century was deeply influenced by the social and economic inequalities established during the colonial period. The desire for land reform, representation, and rights for indigenous populations and mestizos (people of mixed European and indigenous descent) became central issues. Leaders like Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos sought to address these grievances, leading to a protracted struggle for independence from Spanish rule, which was finally achieved in 1821.

In contemporary Mexico, the consequences of the Spanish conquest continue to be felt. Issues of inequality, land rights, and cultural recognition remain significant challenges. The legacy of colonialism has also led to ongoing debates about identity, as Mexican society grapples with its mestizo heritage and the need to honor indigenous cultures. The Zapatista movement in Chiapas, for example, has highlighted the struggles of indigenous communities for autonomy and rights within the modern state.

Moreover, the cultural syncretism initiated during the conquest has given rise to a vibrant and diverse national identity. Mexican culture today is a tapestry woven from indigenous, Spanish, and other influences, resulting in unique expressions in music, literature, cuisine, and art. Festivals such as Día de los Muertos, which blend indigenous and Catholic traditions, showcase the enduring impact of this cultural exchange.

| Aspect | Impact |

|---|---|

| Cultural Exchange | Fusion of Catholicism with indigenous beliefs, leading to unique religious practices. |

| Language | Incorporation of indigenous words into the Spanish language. |

| Art | Blending of European and indigenous artistic styles in architecture and crafts. |

| Demographics | Dramatic population decline due to diseases brought by Europeans. |

| Social Structure | Imposition of a new social hierarchy favoring Spanish settlers. |

| Economic Systems | Establishment of extractive economies that prioritized Spanish wealth. |

| Political Legacy | Influence on governance structures and struggles for independence. |

The timeline of the Spanish conquest and its aftermath is a testament to the resilience of cultures and the complexity of human interactions. The consequences and legacy of this period continue to shape the identity and trajectory of Mexico, highlighting the intertwined nature of history and culture. As Mexico moves forward, the lessons learned from its past remain vital in addressing contemporary challenges and fostering a society that honors its diverse heritage.