The Social Structure of Maya Society

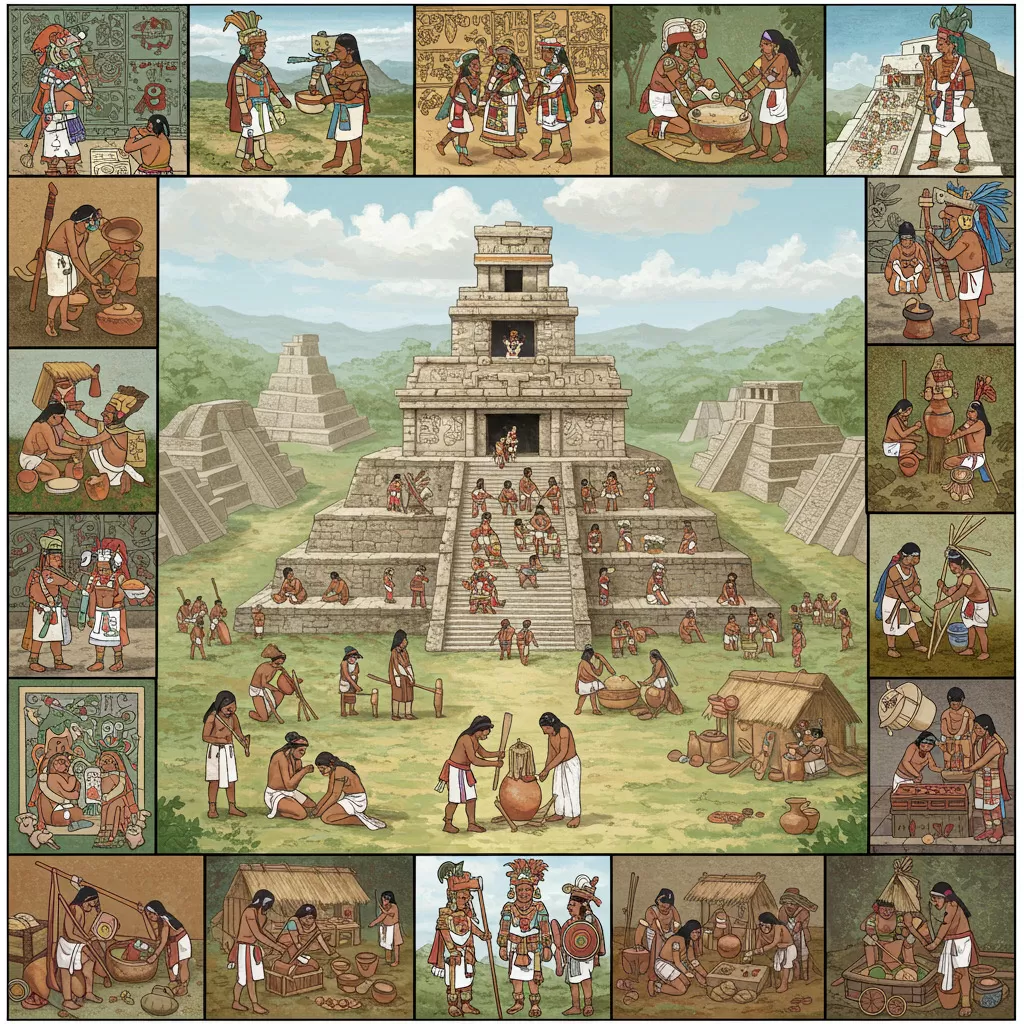

The ancient Maya civilization, renowned for its remarkable achievements in art, science, and architecture, thrived in Mesoamerica for over a thousand years. Understanding the intricate social structure of Maya society is essential to appreciating the complexity of their culture and the factors that contributed to their success. From the towering pyramids of Tikal to the bustling markets of Palenque, the social hierarchy played a pivotal role in shaping daily life and community interactions among the Maya people.

At the heart of this civilization was a well-defined social stratification that delineated roles, responsibilities, and power dynamics. The nobility, commoners, and enslaved individuals each contributed uniquely to the fabric of Maya society, influencing everything from governance to agriculture. Exploring the nuances of this social hierarchy reveals not only the organization of the civilization but also the cultural practices that bound them together, highlighting their religious beliefs, artistic expressions, and methods of knowledge transmission.

Overview of Maya Society Structure

The Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in various fields, had a complex social structure that played a crucial role in the functioning of its society. Understanding this structure requires delving into its historical context and geographic distribution. This overview will explore the intricate layers of Maya society, examining how they shaped not only the daily lives of the Maya people but also their cultural identity and legacy.

Historical Context of the Maya Civilization

The Maya civilization flourished in Mesoamerica, particularly in the regions that now comprise southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. This civilization is estimated to have started around 2000 BCE and reached its peak during the Classic Period (approximately 250 to 900 CE). The historical context of the Maya civilization is essential to understanding its social structure, as it was influenced by various factors, including environmental conditions, trade, warfare, and cultural exchanges with neighboring civilizations.

During the Preclassic period, the Maya began to form small villages, which gradually evolved into complex city-states. By the Classic period, these city-states, such as Tikal, Palenque, and Copán, had developed significant political and economic power. The emergence of a hierarchical society was closely tied to the increasing complexity of governance and the need for organization to manage resources, labor, and trade.

One of the defining features of Maya society was its intricate political systems, which often included a centralized authority led by a king or a noble class. These leaders were believed to have divine connections, which legitimized their power and authority. The role of religion in legitimizing social hierarchy cannot be overstated, as rulers were often seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people, reinforcing their elevated status in society.

Moreover, the Maya civilization was not static; it underwent significant changes due to internal and external pressures. The decline of many city-states during the Terminal Classic period (around 800 to 900 CE) was attributed to factors such as environmental degradation, drought, warfare, and social upheaval. These changes in the political landscape had a profound impact on the social structure of Maya society, leading to adaptations that reshaped their communities in the Postclassic period (900 CE onwards).

Geographic Distribution of Maya Societies

The geographic distribution of Maya societies was diverse, with various environmental conditions influencing their development. The Maya inhabited regions ranging from coastal areas to highland mountains, each presenting unique challenges and opportunities. This diversity resulted in a variety of social structures, cultural practices, and economic activities across different Maya regions.

The lowland areas, characterized by tropical rainforests, supported large populations and were often sites of significant urban centers. These areas thrived on agriculture, primarily the cultivation of maize, beans, and squash, which formed the backbone of the Maya diet. The abundance of resources allowed for the development of complex societies with intricate trade networks, facilitating cultural exchanges and the spread of ideas.

In contrast, the highland Maya faced different environmental challenges, including rugged terrain and varying climates. These regions were home to smaller, more dispersed communities that relied on terrace farming and were often engaged in local trade. The social structure in these areas tended to be less hierarchical, with a stronger emphasis on community cooperation and mutual support.

The geographic distribution of the Maya also influenced their interactions with neighboring cultures, including the Olmecs to the west and the Toltecs to the north. These interactions led to the exchange of goods, technologies, and cultural practices, contributing to the richness and diversity of Maya society. As a result, the social structure of the Maya was not monolithic; it varied significantly across regions, reflecting the environmental, economic, and political realities of each area.

The integration of these diverse communities into a broader Maya identity was facilitated through shared cultural practices, language, and religious beliefs. Despite the variations, there was a common understanding of social roles and hierarchies, which helped to unify the Maya civilization as a whole.

Through the examination of the historical context and geographic distribution of Maya societies, it becomes evident that the social structure of the Maya was deeply intertwined with their environment and history. The complexity of their society allowed for the emergence of a sophisticated cultural legacy that continues to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Social Hierarchy and Class Structure

The social structure of Maya society was intricate and multifaceted, characterized by a well-defined hierarchy that shaped the lives of its members. This hierarchy was not merely a reflection of wealth or occupation but was deeply intertwined with cultural norms, religious beliefs, and political affiliations. Understanding the various strata within Maya society is crucial to grasping the complexities of their civilization, which thrived in Mesoamerica for centuries. This section delves into the social hierarchy and class structure of the Maya, focusing on the roles of nobility, commoners, and the institution of slavery.

The Role of the Nobility

At the pinnacle of the Maya social hierarchy were the nobles, also known as the 'ajaw' or kings, who held significant power and influence over their respective city-states. The nobility was not only composed of the ruling class but also included priests and high-ranking officials who played vital roles in governance, religion, and military leadership. The nobility was tasked with maintaining the favor of the gods and ensuring the prosperity of their people through various religious and political activities.

The status of nobility was often hereditary, passed down from generation to generation, although there were instances where individuals could ascend to noble status through extraordinary achievements in war or by gaining favor with the ruling elite. The nobility enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle, with access to fine clothing, jewelry, and elaborate residences, often adorned with intricate carvings and murals that reflected their power and divine right to rule.

Religious leaders within the noble class held significant sway over the populace, as they were believed to act as intermediaries between the gods and the people. The priests performed intricate rituals and ceremonies to appease the deities and ensure agricultural fertility, which was critical for the sustenance of the Maya civilization. Notably, the political landscape of the Maya was often marred by warfare between rival city-states, and the nobility played a central role in orchestrating these conflicts, which were often justified through religious narratives that emphasized the divine right of rulers to engage in warfare.

Commoners and Their Contributions

Below the nobility was a substantial class of commoners, who made up the bulk of the Maya population. Commoners were primarily engaged in agriculture, which formed the backbone of the Maya economy. They cultivated staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, using sophisticated agricultural techniques like slash-and-burn farming and terracing. The contributions of commoners were vital for sustaining the nobility, as they produced the food that supported both the elite and the larger population.

Commoners were also skilled artisans, producing pottery, textiles, and tools essential for daily life. Their craftsmanship was not only functional but often carried cultural significance, as many of their creations were used in rituals or as offerings to the gods. In addition to agriculture and craftsmanship, commoners participated in construction projects, including the building of temples, pyramids, and other monumental structures that defined the landscape of Maya cities.

Despite their essential role in society, commoners had limited rights and were often subject to the whims of the nobility. They paid tribute in the form of goods and labor, which reinforced the economic and social power of the elite. However, commoners could occasionally rise in status through exceptional service to the elite, military achievements, or as a reward for loyalty, reflecting a degree of social mobility within the rigid hierarchy of Maya society.

The Role of Slavery in Maya Society

Slavery was a significant aspect of Maya society, although it differed from the chattel slavery seen in other parts of the world. The institution of slavery in the Maya civilization was often linked to warfare, as captives taken during conflicts were frequently enslaved. These slaves were typically forced to work on large agricultural estates or serve the nobility in various capacities, including domestic service.

Unlike many other societies, Maya slaves could sometimes earn their freedom, and their social status was not entirely fixed. Enslaved individuals could be adopted into the families of their masters, which occasionally allowed them to integrate into the broader society. However, the conditions of slavery were harsh, and the lives of enslaved people were dictated by the needs and desires of their owners.

While slavery played a role in supporting the economy, it also highlighted the inequalities inherent in Maya society. The existence of slavery underscored the power dynamics between the elite and the lower classes, and it was a reflection of the broader social stratification that defined the civilization. Additionally, the practice of slavery raised ethical questions that resonate with contemporary discussions about human rights and dignity.

Summary of Social Hierarchy

To encapsulate the complex social hierarchy of the Maya civilization, the following table outlines the key characteristics and roles associated with each social class:

| Social Class | Key Roles | Status and Rights |

|---|---|---|

| Nobility | Rulers, priests, military leaders | High status, hereditary privileges, political power |

| Commoners | Farmers, artisans, laborers | Lower status, limited rights, essential contributors |

| Slaves | Domestic servants, laborers | Low status, property of others, vulnerable conditions |

The social hierarchy of the Maya civilization was rooted in a complex interplay of economic, political, and religious factors. Nobility held power and privilege, while commoners formed the backbone of society through their labor and contributions. Slavery, while a means of economic support, underscored the inequalities present within this rich and diverse culture. Understanding these dynamics offers valuable insights into the functioning and sustainability of Maya civilization, revealing both the strengths and vulnerabilities that characterized this ancient society.

Cultural Practices and Community Life

The cultural practices and community life of the Maya civilization provide a fascinating insight into their social structure, beliefs, and everyday existence. The Maya were not just remarkable architects and astronomers; they were also a deeply religious people who placed great importance on community, education, and artistic expression. This section delves into the religious beliefs and practices of the Maya, the transmission of knowledge and education, as well as their rich artistic and architectural heritage, all of which contributed to their unique social identity.

Religious Beliefs and Practices

Religion played a central role in the lives of the Maya. They were polytheistic, worshipping a pantheon of gods and goddesses associated with natural elements and celestial bodies. Each city-state had its patron deities, and the Maya believed that these gods had a direct influence on their agricultural cycles, health, and overall well-being. The Maya also practiced ancestor worship, believing that the spirits of deceased ancestors could influence their lives. This belief system reinforced the social hierarchy, as the elite were often viewed as intermediaries between the gods and the common people.

The Maya calendar, composed of several interlocking cycles, was crucial for their religious practices. The Tzolk'in, a 260-day calendar, was used for ceremonial purposes, while the Haab', a 365-day solar calendar, regulated agricultural activities. These calendars dictated the timing of religious ceremonies and festivals, which were elaborate affairs involving music, dance, and offerings. Major ceremonies included the dedication of temples, rites of passage, and agricultural festivals, which strengthened community bonds and reinforced the social order.

Sacrifices were a significant aspect of Maya religion. Ranging from offerings of food and incense to more elaborate animal and, occasionally, human sacrifices, these acts were seen as necessary to appease the gods and ensure their favor. The infamous ball game, known as Pok-a-Tok, also held religious significance. It was believed to symbolize the struggle between the forces of life and death, and the outcomes were thought to reflect the will of the gods.

Education and Knowledge Transmission

The Maya placed a high value on education and the transmission of knowledge, which was primarily conducted through oral traditions. Knowledge was intertwined with religious practices, and it was often the priests and elite who were responsible for educating the younger generations. They taught not only religious rituals but also mathematics, astronomy, and writing, which were vital for the administration of the city-states and the understanding of their complex calendar systems.

Formal education occurred in schools known as "calpulli," which were organized by social class. The children of the elite received a more comprehensive education, including training in leadership and governance, while commoners focused on practical skills relevant to their daily lives. Women also played a significant role in the education of children, particularly in teaching cultural values and domestic skills.

The Maya developed a sophisticated writing system known as hieroglyphs, which they used to record historical events, religious texts, and astronomical observations. This writing system was crucial for maintaining their cultural identity and passing down knowledge across generations. The codices, which are books made from bark paper, served as repositories of knowledge, containing information on mythology, rituals, history, and the calendar.

Art, Architecture, and Social Identity

The artistic expression of the Maya is one of the most enduring legacies of their civilization. They excelled in various art forms, including sculpture, painting, and pottery, which were often intricately tied to their religious beliefs and social identity. The Maya created stunning murals that adorned their temples and public buildings, depicting scenes from mythology, history, and daily life. These murals not only served an aesthetic purpose but also communicated the values and beliefs of the society.

Architecture is another hallmark of Maya civilization, with monumental structures like pyramids, palaces, and observatories showcasing their advanced engineering skills. Cities such as Tikal, Palenque, and Copán were characterized by their impressive urban layouts and ceremonial centers, which reflected the social hierarchy. The elite lived in more elaborate structures, while commoners inhabited simpler dwellings. The spatial organization of these cities often reinforced the power dynamics within the society, with temples positioned to dominate the landscape and serve as focal points for religious activities.

The significance of art and architecture extended beyond aesthetics; they were also tools of political power and social cohesion. Rulers commissioned grand projects to demonstrate their divine right to govern and to unify the people under a shared cultural identity. The inscriptions found on monuments and stelae often celebrated the achievements of rulers and commemorated important events, thereby linking the political and religious dimensions of Maya life.

The Maya also practiced a variety of crafts, including weaving, pottery, and jewelry-making. These crafts were often produced within the household or community, fostering a sense of identity and belonging. The intricate designs and motifs used in these crafts often held symbolic meanings, reflecting the community's beliefs and values.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Religious Practices | Polytheistic beliefs, ancestor worship, ceremonial calendar, sacrifices. |

| Education | Oral traditions, calpulli schools, focus on religious and practical knowledge. |

| Art and Architecture | Murals, monumental structures, crafts, and their role in social identity. |

In conclusion, the cultural practices and community life of the Maya reveal a society rich in traditions and beliefs. Their religion, education, and artistic achievements were not only integral to their identity but also served to reinforce the social hierarchy and cohesion within their communities. The legacy of the Maya civilization continues to influence modern culture and is a testament to their extraordinary contributions to human history.