The Social Hierarchy of the Maya: Nobles, Commoners, and Slaves

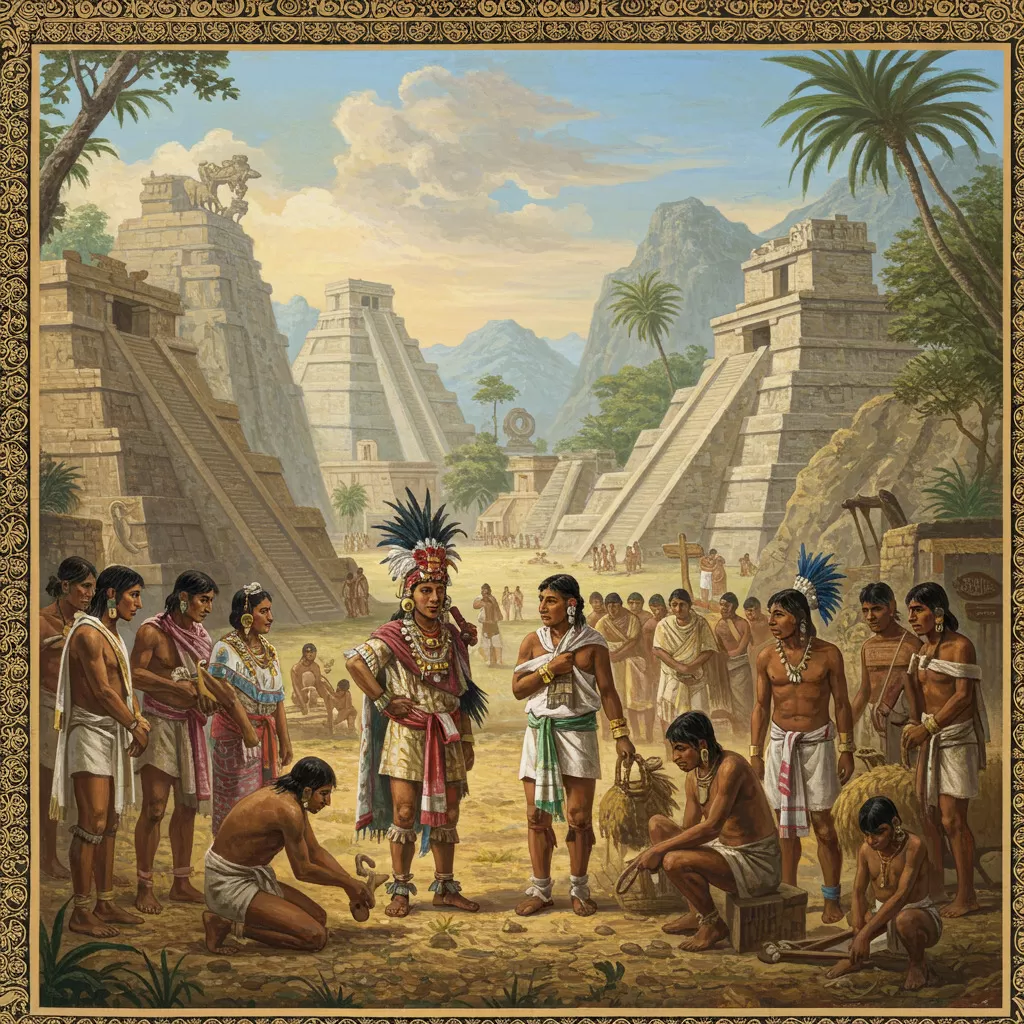

The intricate tapestry of Maya civilization reveals not only remarkable achievements in art, science, and architecture but also a complex social hierarchy that defined the lives of its people. From the towering pyramids to the bustling marketplaces, the structure of society played a pivotal role in shaping the interactions and relationships among the various classes. Understanding this social hierarchy offers valuable insights into the values, beliefs, and daily experiences of the Maya, as well as the forces that influenced their development over centuries.

At the pinnacle of this hierarchy were the nobles, a ruling elite whose power was intertwined with religious authority and political influence. Their roles and responsibilities extended beyond governance, as they were central figures in the spiritual life of the community. Beneath them, commoners formed the backbone of the society, contributing to its economy through agriculture and craftsmanship, while the presence of slaves reflected the darker aspects of social stratification. By exploring these distinct groups and their interactions, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of Maya civilization and its enduring legacy.

Understanding the Social Structure of the Maya Civilization

The Maya civilization, one of the most sophisticated ancient cultures in Mesoamerica, flourished in what is now Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. The social structure of the Maya was complex and hierarchical, encompassing various classes that played distinct roles within society. Understanding this social structure is crucial to grasping the political, economic, and cultural dynamics that defined the Maya civilization.

Historical Context of Maya Society

The Maya civilization emerged around 2000 BCE and reached its peak during the Classic Period (approximately 250-900 CE). This era was characterized by the construction of monumental architecture, the development of a sophisticated writing system, and advancements in mathematics and astronomy. The Maya were not a monolithic society; they comprised numerous city-states that often engaged in trade, warfare, and political alliances.

Each city-state had its own ruler and was often at the center of a network of smaller settlements and villages. The social structure was influenced by various factors, including geography, economy, and the interaction with neighboring cultures. The Maya relied heavily on agriculture, particularly maize cultivation, which supported a growing population and allowed for the development of a wealthy elite class.

As the civilization grew, so did the complexity of its social hierarchy. The rulers, often seen as divine or semi-divine figures, held significant power and were responsible for maintaining order and prosperity within their realms. This led to the establishment of a social order that was deeply intertwined with religious beliefs, as the Maya viewed their rulers as intermediaries between the gods and the people.

Importance of Social Hierarchy

The social hierarchy of the Maya played a critical role in the functioning of their society. It dictated not only the distribution of power and resources but also the social interactions and relationships among various groups. At the top of this hierarchy were the nobles, followed by commoners, and at the bottom, the slaves. Each group had defined roles and responsibilities that contributed to the overall stability and continuity of Maya civilization.

The importance of this social structure can be seen in various aspects of Maya life, including governance, religious practices, and economic activities. The ruling class was responsible for making laws, conducting rituals, and overseeing trade, while commoners formed the backbone of the economy through their labor and craftsmanship. Slaves, although at the lowest tier, were integral to the agricultural and construction efforts within the society.

This hierarchical organization allowed for a division of labor that enhanced productivity and facilitated the administration of complex city-states. It also created a sense of identity and belonging within each class, as individuals were often born into their roles and expected to fulfill them throughout their lives. Understanding this social hierarchy is essential for comprehending the broader cultural, political, and economic frameworks of the Maya civilization.

The Nobility: Rulers and Elite Class

The nobility of the Maya civilization consisted of rulers, priests, and high-ranking officials. This elite class held considerable power and influence over the political and religious life of the society. Nobles were often related to the ruling family and were tasked with various responsibilities that included governance, military leadership, and conducting religious ceremonies.

Roles and Responsibilities of Maya Nobles

Nobles played a critical role in maintaining the social order of Maya society. They were responsible for collecting tribute from commoners, overseeing trade, and managing agricultural production. Nobles also acted as military leaders during conflicts with neighboring city-states, and their successes in warfare often enhanced their status and power.

In addition to their political duties, nobles were also deeply involved in religious practices. They conducted rituals to appease the gods and ensure the prosperity of their city-state. The elite class had access to education and were often literate, enabling them to read and write in the Maya hieroglyphic script. This literacy allowed them to document history, create codices, and participate in the intellectual life of the civilization.

The Power Dynamics Among the Elite

Power dynamics among the nobility were often complex and fluid. While the ruling class wielded significant authority, rivalries and alliances frequently emerged among noble families. These power struggles could lead to conflicts and even civil wars as different factions vied for control of city-states.

Marriage alliances were a common strategy used by nobles to consolidate power and secure political alliances. By marrying into other noble families, rulers could strengthen their positions and create networks of loyalty that extended across city-states. These intricate relationships among the elite class were essential for maintaining stability and governance in the ever-changing political landscape of the Maya civilization.

Religious and Political Influence

The religious and political influence of the Maya nobility was profound. Rulers were often considered divine or semi-divine figures, believed to have a special connection to the gods. This belief granted them the authority to govern and conduct rituals essential for the well-being of their society. Nobles participated in elaborate ceremonies, including bloodletting and human sacrifices, to appease the gods and ensure agricultural fertility.

Religious leaders, often drawn from the noble class, played a crucial role in interpreting omens and guiding political decisions based on their understanding of the divine will. This intertwining of religion and politics created a system in which the elite maintained control and justified their authority through spiritual means.

Commoners and Their Daily Lives

Commoners formed the bulk of the Maya population and were essential for the functioning of society. While they held a lower social status than nobles, commoners played a critical role in agriculture, trade, and craftsmanship. Understanding their daily lives provides insight into the broader social dynamics of the Maya civilization.

Occupations and Economic Contributions

The majority of commoners were engaged in agriculture, working the land to produce staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash. They utilized advanced farming techniques, including slash-and-burn agriculture and terracing, to maximize their yields. In addition to farming, many commoners were skilled artisans who produced pottery, textiles, and tools, contributing to the local economy and trade networks.

Trade was a significant aspect of Maya life, with commoners participating in both local and long-distance commerce. They exchanged goods such as textiles, ceramics, and agricultural products at markets, facilitating economic interactions among different city-states. This economic contribution was vital for the sustenance of the elite class, who relied on commoners for their wealth and resources.

Social Status and Community Roles

Despite their lower social status, commoners held important roles within their communities. They were often organized into extended family units, which provided social support and cohesion. Local governance was typically managed by councils or assemblies composed of respected commoners, allowing them to have a voice in community decisions.

Social status among commoners could vary based on factors such as occupation, wealth, and contributions to the community. Skilled artisans or successful farmers could gain respect and influence, while those who struggled economically might face marginalization. Nevertheless, commoners shared a collective identity that was essential for the unity and stability of Maya society.

Education and Cultural Practices

While formal education was primarily reserved for the elite, commoners received practical education through apprenticeships and family traditions. Children learned the skills necessary for their future roles, whether in agriculture, crafts, or trade. Oral traditions played a significant role in passing down knowledge, stories, and cultural practices.

Cultural practices among commoners included various celebrations, festivals, and rituals that reinforced community bonds and cultural identity. These events often revolved around agricultural cycles, religious observances, and communal gatherings, allowing commoners to participate in the rich cultural tapestry of Maya civilization.

Slavery in Maya Society

Slavery was a recognized institution within the Maya civilization, though the nature and extent of slavery varied significantly across different regions and periods. Understanding the origins and types of slavery, as well as the experiences of slaves, sheds light on the darker aspects of Maya society.

Origins and Types of Slavery

Slavery in the Maya civilization had multiple origins, including warfare, debt, and social status. Captives taken during conflicts were often enslaved, serving as a source of labor for the elite. Additionally, individuals who fell into debt could become slaves to repay their obligations, a practice that reflected the economic vulnerabilities faced by some commoners.

There were different types of slaves in Maya society, including those who worked in agriculture, domestic service, and skilled labor. Some slaves were assigned to specific tasks, while others might be used in temple service or as human sacrifices during religious ceremonies. The treatment of slaves could vary significantly, ranging from harsh labor to relative autonomy depending on their roles and the specific circumstances of their enslavement.

Treatment and Daily Life of Slaves

The treatment of slaves in Maya society was complex and often harsh. Many slaves were subjected to arduous labor, working in fields or on construction projects. However, some slaves could earn their freedom through various means, such as successful service or the payment of debts. The daily life of slaves was characterized by a lack of autonomy, as they were considered property and had limited rights.

Despite their status, slaves could form social bonds and maintain family relationships. Some slaves were allowed to marry, and their children might not inherit their enslaved status, depending on the circumstances. This aspect of slavery created a nuanced social fabric, with slaves sometimes playing integral roles in the households they served.

Impact of Slavery on Maya Culture and Economy

The institution of slavery had significant implications for Maya culture and economy. Slavery provided a source of labor that supported the agricultural and construction efforts essential for the prosperity of the elite class. The reliance on slave labor allowed the nobility to amass wealth and resources, further entrenching social hierarchies.

Culturally, the presence of slavery influenced social dynamics and perceptions of power. The elite class often justified the practice through religious beliefs and ideological narratives that portrayed enslaved individuals as fulfilling a necessary role in the broader cosmological order. This cultural framing helped to maintain the societal structure and perpetuated the cycles of inequality.

In conclusion, the social structure of the Maya civilization was a complex and multi-faceted system that dictated the roles and relationships among different classes. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for grasping the political, economic, and cultural dynamics that characterized one of Mesoamerica's most remarkable civilizations. Through the examination of the nobility, commoners, and slaves, we can appreciate the intricate web of social interactions that shaped the lives of the Maya and their enduring legacy in history.

The Nobility: Rulers and Elite Class

The Maya civilization, which spanned from approximately 2000 BCE to the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century CE, was characterized by a complex social structure. At the apex of this hierarchy sat the nobility, a class of rulers and elites who wielded considerable power over the political, religious, and economic aspects of Maya life. Understanding the roles, responsibilities, and dynamics of this elite group is essential for grasping the intricacies of Maya society.

Roles and Responsibilities of Maya Nobles

The Maya nobility comprised kings, queens, and high-ranking officials who were often descendants of prominent families. These individuals were not only responsible for governance but also played crucial roles in the religious and cultural life of their communities. The responsibilities of the nobility included:

- Political Leadership: Nobles were the decision-makers in their respective city-states, overseeing the administration and execution of laws. They were often involved in diplomacy, negotiating alliances and managing conflicts with neighboring territories.

- Religious Duties: The Maya believed in a pantheon of gods, and the nobility served as intermediaries between the divine and the people. They conducted important rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices to appease the gods, ensuring cosmic balance and agricultural prosperity.

- Military Command: Noble warriors led military campaigns to expand territory or defend their city-states. Their valor in battle was essential for maintaining prestige and power.

- Economic Oversight: Nobles controlled land and resources, which were vital for the economy. They oversaw agricultural production and trade, ensuring that their city-states thrived.

These roles were not only significant for governance but also for the perpetuation of their elite status. The nobility's ability to maintain order and prosperity was crucial in legitimizing their power and influence among the populace.

The Power Dynamics Among the Elite

The power dynamics within the Maya nobility were complex and often marked by competition and rivalry. While kings and queens held the highest authority, their power was frequently challenged by other noble families. This intra-elite competition played a vital role in shaping political landscapes in Maya city-states.

Succession was one of the critical issues that could lead to conflict. The Maya practiced a form of dynastic rule, where leadership was often passed down through family lines. However, succession was not always straightforward. The selection of heirs could lead to disputes among brothers, cousins, or other relatives, each vying for influence and control. Such rivalries could result in civil wars, destabilizing city-states and shifting power balances.

The relationship between nobles and the common populace also influenced power dynamics. While nobles were at the top of the social hierarchy, they relied on the support of commoners for labor, tribute, and military service. This interdependence meant that the nobility had to maintain a delicate balance of power. If commoners felt oppressed or exploited, they could rebel, threatening the nobles' authority. This dynamic fostered a system where the nobility had to engage in a form of social contract, ensuring the welfare of the lower classes to maintain their legitimacy.

Religious and Political Influence

The interplay between religion and politics in Maya society was profound, with the nobility often serving dual roles as both political leaders and religious figures. This duality enabled them to wield significant influence over their subjects, as they were seen as divinely sanctioned rulers.

Maya rulers were often considered to be of divine descent or chosen by the gods. This belief was reinforced through elaborate ceremonies, where nobles would perform rituals to communicate with deities. The association with the divine not only legitimized their authority but also reinforced their social status. Nobles were often depicted in murals and inscriptions as powerful figures engaging with gods, emphasizing their important role in maintaining cosmic order.

Political decisions were deeply intertwined with religious beliefs. For example, the timing of agricultural activities, such as planting and harvesting, was often dictated by religious calendars. Nobles were responsible for conducting ceremonies to ensure favorable weather and bountiful crops, directly linking their political and religious responsibilities.

The construction of monumental architecture, such as temples and palaces, served both as a display of power and as a religious center. Nobles commissioned elaborate structures that not only represented their authority but also acted as venues for religious ceremonies, further solidifying their influence over both political and spiritual realms.

Moreover, the art and iconography of the Maya often depicted noble figures in connection with gods and supernatural beings, reinforcing their role as intermediaries between the divine and the earthly realms. This blend of political and religious authority was a hallmark of Maya civilization and contributed to the stability and longevity of their city-states.

Commoners and Their Daily Lives

The Maya civilization, renowned for its complex social structure, monumental architecture, and advanced knowledge in mathematics and astronomy, also had a vibrant and multifaceted life among its commoners. While the elite class, comprising nobles and rulers, often garners attention in historical narratives, the majority of the population comprised commoners who played a crucial role in the functioning and sustainability of Maya society. Understanding the daily lives of these individuals provides valuable insight into the culture, economy, and social dynamics of the Maya civilization.

Occupations and Economic Contributions

Commoners in Maya society were primarily engaged in agricultural activities, which formed the backbone of the civilization’s economy. The fertile lands of the Maya lowlands allowed for the cultivation of staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash. These crops were not only essential for sustenance but also played a significant role in religious rituals and social gatherings. The methods employed in agriculture included slash-and-burn techniques, which involved clearing land by cutting down vegetation and burning it to enrich the soil.

In addition to agriculture, commoners participated in various crafts and trades. Artisans skilled in pottery, weaving, and stone carving contributed to the economy by producing goods for local consumption and trade. The production of textiles, particularly cotton clothing, was a significant aspect of common life, with women often taking the lead in weaving. The crafting of tools and ceremonial objects also provided vital resources for both everyday life and religious practices.

Trade networks facilitated the exchange of goods not only within communities but also between different Maya city-states. Commoners would engage in barter, trading surplus agricultural products for items they could not produce themselves, such as obsidian tools, cacao, and luxury goods. This exchange system contributed to the economic interdependence of various regions and enhanced the social cohesion of Maya society.

Social Status and Community Roles

The social status of commoners in the Maya hierarchy was primarily defined by their occupation and wealth, although it remained distinct from that of the elite. While commoners did not possess the same privileges as the nobles, their roles were essential for the societal structure. They were responsible for labor-intensive tasks that supported both the economy and the religious life of the community.

Within their communities, commoners held various roles that contributed to social organization. For instance, community leaders or 'ahau' were often chosen from the common population to oversee local affairs, especially in the absence of nobles. This allowed for a degree of representation and participation in governance, albeit limited. Furthermore, commoners participated in communal projects, such as the construction of temples and public buildings, which fostered a sense of unity and belonging.

Religious practices were integral to daily life, and commoners actively participated in rituals and ceremonies. They engaged in agricultural festivals that honored deities associated with fertility and harvest, reinforcing their connection to the land and spirituality. Such practices were significant in maintaining social order and cohesion, as they provided opportunities for communal bonding and collective identity.

Education and Cultural Practices

Education for commoners in Maya society was not formalized in the same manner as it was for the elite, who often had access to specialized schools and tutors. However, knowledge was transmitted through oral traditions, familial teachings, and community involvement. Commoners learned essential skills such as farming techniques, artisanal craftsmanship, and the cultural significance of rituals from their elders and through participation in community events.

Cultural practices among commoners included storytelling, music, and dance, which were vital for the transmission of history and values. Festivals often featured performances that celebrated agricultural cycles, historical events, and religious beliefs. These cultural expressions not only served as entertainment but also reinforced social norms and collective memory, creating a shared identity among community members.

The role of women in the cultural and educational landscape of commoners was particularly significant. Women were typically responsible for managing household affairs, including food preparation and child-rearing. They also played a crucial role in the crafting of textiles and pottery, contributing to both the economy and cultural heritage. The skills and knowledge passed down from mother to daughter ensured the continuity of cultural practices and traditions within families and communities.

The Impact of Geography on Daily Life

The geographical diversity of the Maya region influenced the daily lives of commoners significantly. The lowland areas, characterized by tropical rainforests, provided rich agricultural opportunities but also posed challenges such as flooding and soil exhaustion. In contrast, highland regions offered different resources and farming techniques, impacting local economies and lifestyles.

Additionally, the availability of resources such as water, timber, and stone influenced settlement patterns and community organization. Commoners adapted their agricultural practices to fit the environmental context, utilizing terracing, irrigation, and crop rotation to maximize productivity. The geography of the Maya region not only shaped their agricultural practices but also played a role in social interactions and trade routes among different communities.

Festivals and Community Gatherings

Festivals were significant events in the lives of commoners, serving as opportunities for socialization, cultural expression, and spiritual connection. The Maya calendar, which was intricately tied to agricultural cycles, dictated a variety of festivals throughout the year. Commoners participated in ceremonies that honored agricultural deities, celebrated harvests, and marked important life stages such as birth and marriage.

These gatherings often involved communal feasting, music, and dance, fostering a sense of belonging and community cohesion. They also provided an avenue for the expression of cultural identity and the reinforcement of social bonds among commoners. The participation of commoners in these events highlighted their essential role in the social fabric of Maya civilization.

The Role of Religion in Daily Life

Religion permeated every aspect of daily life for commoners in Maya society. The belief in a pantheon of gods and the importance of ritual offerings were central to their existence. Commoners engaged in daily practices such as prayers and offerings to ensure favorable agricultural outcomes and protection from natural disasters.

Temples and altars were often focal points in communities, where commoners would gather for communal worship and rituals. The participation of commoners in religious practices not only reinforced their spiritual beliefs but also contributed to the social hierarchy, as religious leaders often held significant power and influence within communities.

Artistic Expression and Daily Life

The artistic expression of commoners was not limited to the elite’s extravagant depictions in hieroglyphs or monumental architecture. Instead, commoners expressed their creativity through pottery, textiles, and murals, often reflecting their daily lives, beliefs, and cultural values. The motifs and designs used in these artistic endeavors often depicted scenes of agricultural life, community gatherings, and spiritual symbols.

Art was not merely a form of decoration but served functional purposes as well. Pottery was used for both cooking and ceremonial purposes, while textiles often carried social significance, indicating status and identity. The artistic contributions of commoners enriched the cultural heritage of the Maya civilization, showcasing their creativity and resilience.

Challenges Faced by Commoners

Despite their vital role in society, commoners faced numerous challenges that affected their daily lives. Economic pressures, such as crop failures due to drought or pests, could lead to food scarcity and hardship. Additionally, commoners were often subject to the demands of the elite, who required labor for construction projects or military campaigns.

Social inequalities were also prevalent, as the wealth and power of the elite often overshadowed the contributions of commoners. While some could achieve higher social standings through exceptional skills or service, the vast majority remained in a subordinate position within the hierarchy. The increasing strain on resources, especially as populations grew, posed threats to the stability of commoner life and the broader Maya civilization.

Conclusion

The daily lives of commoners in the Maya civilization were rich and complex, characterized by their essential contributions to agriculture, crafts, and cultural practices. While often overshadowed by the narratives of the elite, the experiences of commoners reveal the resilience and resourcefulness of a population that formed the backbone of Maya society. Their roles in community, economy, and spirituality enriched the cultural tapestry of the Maya civilization and underscored the interconnectedness of all social strata in this ancient society.

Slavery in Maya Society

The institution of slavery in Maya society is a complex and multifaceted aspect of their civilization, deeply intertwined with their cultural, economic, and social structures. While the Maya are often celebrated for their advancements in mathematics, astronomy, and art, the reality of their social hierarchy included a system of slavery that served significant roles in their daily lives and economic activities. This section delves into the origins and types of slavery in Maya society, the treatment and daily life of slaves, and the broader impact of slavery on Maya culture and economy.

Origins and Types of Slavery

Slavery in Maya civilization can be traced back to the early periods of their history, with its roots in warfare, debt, and the socio-economic dynamics of the time. The Maya practiced a form of slavery that was not static; it evolved over centuries and varied significantly across different city-states and regions.

One of the primary origins of slavery was warfare. The conquest of rival groups often resulted in the capture of individuals who were then enslaved. These captives were typically used for labor, but they could also be sacrificed in religious rituals, highlighting the duality of their existence as both laborers and offerings to the gods. The warfare context established a precedent where the victor would not only claim territory but also subjugate the vanquished population.

In addition to war, debt played a crucial role in the enslavement process. Individuals who could not repay debts could find themselves and their families sold into slavery. This form of slavery, termed debt bondage, meant that a person’s economic situation directly influenced their social standing and freedom. Over time, the lines between voluntary servitude and involuntary slavery became blurred, as individuals entered agreements that ultimately led to lifelong servitude.

There were also social and economic factors involved in the types of slavery practiced by the Maya. Slaves could be divided into different categories, including:

- War Captives: Individuals taken during military campaigns.

- Debt Slaves: Those who sold themselves or family members to pay debts.

- Born Slaves: Children born to enslaved individuals automatically inherited their status.

- Domestic Slaves: Individuals who worked in households, often performing personal services.

Treatment and Daily Life of Slaves

The treatment of slaves in Maya society varied significantly depending on their roles, the region, and the individual slave owner. In some cases, slaves were integrated into households, while in others, they faced harsh living conditions and severe punishment.

Domestic slaves often lived in the households of their owners and could be treated with a degree of care, especially if they served as caregivers or nannies for children. These individuals might be given food, shelter, and even clothing, although their freedom was still severely restricted. They were expected to perform daily chores and could be subjected to the whims of their owners, leading to a complex relationship that sometimes included affection but often resulted in exploitation.

In contrast, slaves working in agriculture or construction faced much harsher realities. They were frequently subjected to grueling labor under the sun, with little regard for their well-being. Such slaves were often worked until they could no longer perform their tasks, at which point they could be discarded, sold, or replaced. The physical toll of this labor was significant, contributing to a high mortality rate among enslaved populations.

Despite the challenging conditions, slaves in Maya society could occasionally gain opportunities for advancement. Some were able to purchase their freedom or earn it through exemplary service, particularly if they demonstrated skill in a trade or craft. This potential for mobility, albeit limited, indicates that the social structure was not entirely rigid and allowed for some individual agency.

Impact of Slavery on Maya Culture and Economy

Slavery had profound implications for Maya culture and economy, shaping their social dynamics and influencing the development of their civilization. Economically, the reliance on slave labor facilitated the growth of agricultural production and the construction of monumental architecture, which were critical components of Maya society.

The agricultural sector heavily relied on slave labor to cultivate crops such as maize, beans, and cacao, which were staples in the Maya diet and essential for trade. This labor allowed for surplus production, which in turn supported the elite class and contributed to the wealth of city-states. The surplus also enabled trade relationships with neighboring cultures, enhancing the Maya's economic standing in the region.

Moreover, the construction of temples, pyramids, and other public works was often executed by slave labor. These monumental structures served both religious and political purposes, reinforcing the power of the elite and the role of religion in society. The visibility of these projects symbolized the strength and sophistication of Maya civilization, even as they rested on the backs of enslaved individuals.

On a cultural level, the existence of slavery influenced religious practices and social norms. The Maya often viewed the act of capturing and sacrificing individuals in warfare as a means of appeasing the gods. This practice reinforced the idea that slaves were not only laborers but also valuable offerings, intertwining their fates with the spiritual beliefs of the society.

Furthermore, the existence of a slave class contributed to the social stratification that characterized Maya civilization. The clear division between nobles, commoners, and slaves solidified the power dynamics within society, creating an environment where the elite maintained dominance through economic control and religious justification. This stratification was crucial in sustaining the political structures of the city-states, facilitating the emergence of a ruling class that relied on both labor and tribute from the lower classes.

In conclusion, the institution of slavery in Maya society was a critical component of their social hierarchy, contributing to economic production, cultural practices, and the maintenance of power structures. Understanding this aspect of Maya civilization provides insight into the complexities of their society and the multifaceted roles that individuals played within it. The legacy of slavery in the Maya world is a reminder of the human cost of civilization and the intricate web of relationships that defined their ancient culture.