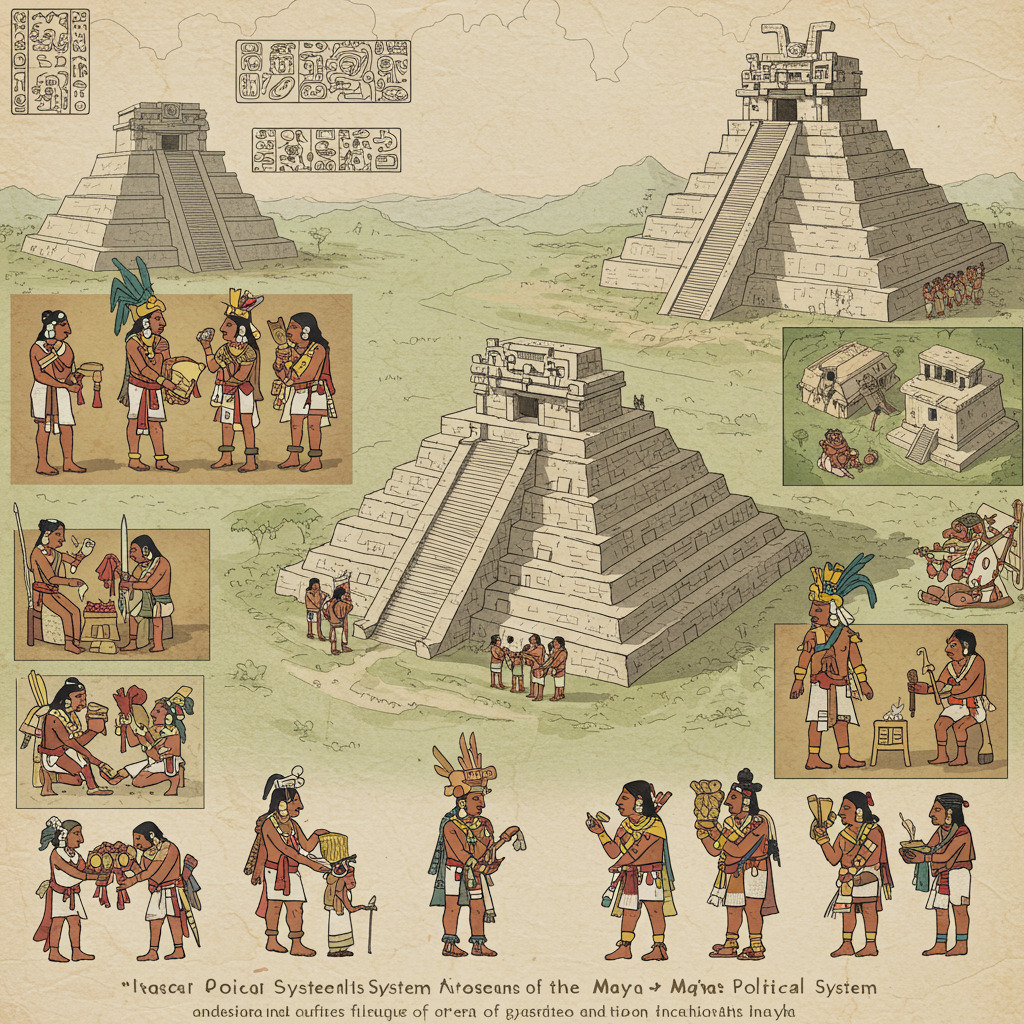

The Political Structure of the Maya: City-States and Dynasties

The ancient Maya civilization, renowned for its remarkable achievements in astronomy, architecture, and art, also possessed a complex and dynamic political structure that shaped its city-states across Mesoamerica. These city-states, characterized by their independent governance and rich cultural identities, were often ruled by dynasties that wielded significant power and influence. Understanding the intricacies of this political system provides valuable insights into how the Maya organized their societies and responded to both internal and external challenges.

The political landscape of the Maya was marked by a diverse array of city-states, each with unique geographical features and urban planning strategies. This diversity not only influenced their economic systems and trade practices but also dictated the social hierarchies that emerged within these communities. As we delve into the defining characteristics of these city-states, we uncover the interconnectedness of governance, economy, and social structures that made the Maya civilization one of the most fascinating in history.

Moreover, the interplay between religion and politics played a crucial role in the Maya's governance, as rituals and ceremonies often underscored the authority of rulers and their dynasties. The impact of warfare and alliances further complicated the political dynamics, shaping relationships among city-states and affecting their longevity. By exploring these themes, we can appreciate the enduring legacy of the Maya political structures and their relevance in understanding contemporary Central American societies.

Overview of Maya Political Structure

The Maya civilization, one of the most remarkable and complex societies of Mesoamerica, had a distinctive political structure that was integral to its development and sustainability. The political organization of the Maya was characterized by a decentralized system of governance, where city-states, known as "k'uhul ajaw" or sacred lords, ruled independently but often engaged in alliances, rivalries, and trade. Understanding the intricacies of this political framework is essential for appreciating the sophistication of Maya society.

Definition of City-States

Maya city-states were independent political entities that comprised a central urban area and its surrounding rural lands. Each city-state functioned autonomously with its own ruler, government, and social structure. The concept of city-states in the Maya context differs from the modern understanding of nation-states; rather, they were often centered around a major ceremonial center or urban hub, which served as the political, religious, and economic focal point.

City-states such as Tikal, Calakmul, Palenque, and Copán were not merely geographic locations but vibrant centers of culture and power. Each city-state was characterized by its unique architectural styles, political alliances, and economic activities. The rulers of these city-states wielded considerable power, often legitimized through divine ancestry and religious authority.

The Role of Dynasties

Dynasties played a pivotal role in the political landscape of the Maya civilization. These ruling families often claimed descent from gods or legendary figures, which enhanced their legitimacy and authority. Dynastic rule was not just about hereditary succession; it encompassed a complex web of alliances, marriages, and rivalries that influenced the stability and power of a city-state.

The continuity of dynasties was crucial for maintaining political order. Rulers would often engage in strategic marriages to strengthen alliances with other city-states or to secure trade routes. The political significance of these dynasties extended beyond their immediate territories; they influenced the broader regional dynamics through warfare, diplomacy, and cultural exchange.

Key Characteristics of Maya City-States

Understanding the key characteristics of Maya city-states provides insight into how these entities functioned and interacted with one another. From geography and urban planning to social hierarchy and economic systems, these elements were fundamental in shaping the dynamics of Maya civilization.

Geography and Urban Planning

The geography of the Maya region, which spans parts of modern-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador, significantly influenced urban planning and the development of city-states. The landscape varied from dense jungles to arid plains, leading to diverse settlement patterns. Major city-states were often located near rivers or other water sources, which facilitated agriculture and transportation.

Maya urban planning was highly sophisticated, characterized by a layout that reflected religious and political significance. The central plaza was typically surrounded by important structures such as temples, palaces, and ball courts. The orientation of buildings often had astronomical alignments, highlighting the interconnection between politics, religion, and the cosmos.

In addition to ceremonial architecture, the Maya developed extensive agricultural terraces and irrigation systems. These innovations allowed for the support of large populations and contributed to the economic viability of city-states. The organization of urban space within these city-states exemplified the Maya's understanding of their environment and their ability to adapt to it.

Social Hierarchy and Governance

The social hierarchy within Maya city-states was complex and stratified, with a clear distinction between the elite and commoners. At the top of the hierarchy was the ruling class, consisting of the king (ajaw) and his family, who held both political and religious authority. Below them were the nobles, priests, and scribes, who played crucial roles in governance, religious practices, and record-keeping.

Commoners, including farmers, artisans, and laborers, formed the majority of the population. While they had limited political power, their labor was essential for the economic sustainability of city-states. The governance structure often allowed for some degree of local participation, with councils or assemblies that included representatives from various social classes, albeit primarily from the elite.

Governance in Maya city-states was characterized by a blend of autocratic rule and communal decision-making. The ajaw had significant power, but his authority was often checked by the elite class and the need for consensus in major decisions. This system allowed for flexibility and adaptation, enabling city-states to respond to internal and external challenges effectively.

Economic Systems and Trade

The economic systems of Maya city-states were diverse and multifaceted, based primarily on agriculture, trade, and tribute. The Maya practiced a form of agriculture known as "swidden" or slash-and-burn farming, which involved clearing land for cultivation. Crops such as maize, beans, and squash were staple foods that supported the population.

Trade was a critical component of the Maya economy, with city-states engaging in extensive networks that facilitated the exchange of goods and resources. Items such as jade, cacao, textiles, and obsidian were highly valued and often used as currency. The Maya established trade routes that connected various city-states, promoting economic interdependence.

Tribute systems were also integral to the economic framework, where subordinate city-states were required to pay tribute to their overlords. This practice reinforced political hierarchies and created a system of mutual obligation that sustained relationships between city-states.

Influential Dynasties in Maya History

The history of the Maya civilization is marked by influential dynasties that shaped political, cultural, and economic landscapes. Each dynasty contributed to the development of city-states and left a lasting impact on Maya history.

The Kaan Dynasty

The Kaan Dynasty, also known as the Snake Dynasty, was one of the most powerful ruling families in the Maya region. Centered in the city-state of Calakmul, the Kaan Dynasty played a significant role in the political dynamics of the Classic Maya period. Their influence extended through strategic marriages, military conquests, and alliances with other city-states.

One of the most notable rulers of the Kaan Dynasty was Yuknoom Ch'een II, who expanded Calakmul's territory and engaged in conflicts with rival city-states, particularly Tikal. The rivalry between Calakmul and Tikal exemplified the competitive nature of Maya politics, with each seeking to assert dominance over the other.

The Tikal and Calakmul Rivalry

The rivalry between Tikal and Calakmul was a defining feature of Maya political history. These two city-states, located in close proximity to each other in modern-day Guatemala, engaged in a series of conflicts that shaped their political landscapes. Tikal, known for its monumental architecture and powerful rulers, was often seen as a cultural and political beacon of the Maya civilization.

Calakmul, on the other hand, strategically positioned itself as a powerful military force, often challenging Tikal's dominance. The struggle for power between these two city-states resulted in shifting alliances and a complex network of political maneuvering. The Tikal-Calakmul rivalry not only influenced military strategies but also affected trade routes and cultural exchanges.

The Role of Women in Power

Women in Maya society held significant roles that extended beyond traditional expectations. While male rulers were predominant, there are numerous instances of powerful women who influenced politics and governance. Queens, known as "ixim" or "lady," often acted as regents or co-rulers alongside their husbands, particularly when the king was absent or unable to rule.

One notable example is Lady Sak K'uk', the mother of the famous ruler K'inich Janaab' Pakal of Palenque. She played a crucial role in his ascension to the throne and in the governance of the city-state during his early reign. The presence of women in ruling roles highlights the complexity of gender dynamics within Maya political structures and challenges the notion of a strictly patriarchal society.

Religious and Ceremonial Aspects of Governance

The intertwined nature of religion and politics in Maya city-states was fundamental to their governance. Religious beliefs and practices were not isolated from political authority; rather, they were integral to the legitimacy and functioning of rulers.

The Connection Between Religion and Politics

The Maya believed that their rulers were divinely chosen, often tracing their lineage back to gods or mythical ancestors. This connection between the divine and the political was crucial in legitimizing the authority of the ajaw. Rulers conducted rituals and ceremonies to communicate with the gods and ensure their favor, which was believed essential for the prosperity of the city-state.

Religious leaders often played prominent roles in governance, advising rulers and interpreting the will of the gods. The centrality of religion in political life meant that the ajaw was not only a political leader but also a spiritual guide, responsible for maintaining the cosmic order. Religious festivals and ceremonies were closely linked to political events, reinforcing the legitimacy of rulers and the social cohesion of their communities.

Rituals and Their Political Significance

Rituals served as a means of solidifying political power and reinforcing social hierarchies within Maya society. Major ceremonies, such as the dedication of temples or the accession of a new ruler, were public spectacles that affirmed the ruler's authority and the city's religious significance.

These rituals often involved elaborate offerings, including sacrifices, which were believed to appease the gods and ensure fertility, health, and victory in warfare. The participation of various social classes in these ceremonies emphasized the interconnectedness of religion, politics, and society.

Through these rituals, rulers communicated their power and divine favor to their subjects, fostering loyalty and reinforcing their political authority. The political significance of rituals extended beyond their immediate context, influencing relationships between city-states and impacting broader regional dynamics.

Impact of Warfare on Political Dynamics

Warfare was an essential element of the political landscape in Maya civilization, shaping relationships between city-states and influencing their governance structures. The dynamics of conflict and alliances were critical to understanding the evolution of Maya political systems.

Military Strategies and Alliances

The Maya developed sophisticated military strategies that were crucial for the defense of their city-states and the expansion of their territories. Warfare was often driven by the need for resources, such as arable land, tribute, and access to trade routes. Military campaigns were usually led by the ruling elite, who sought to enhance their power and prestige through successful conquests.

Alliances were also a common tactic in Maya warfare, with city-states forming coalitions to strengthen their military capabilities against common enemies. These alliances were often fluid, shifting in response to changing political landscapes and rivalries. The ability to forge and maintain alliances was a key indicator of a city-state's political acumen and strategic foresight.

Consequences of Conflict on City-State Relations

The consequences of warfare were profound, affecting not only the immediate outcomes of battles but also the long-term political dynamics between city-states. Victorious city-states often imposed tribute on their defeated rivals, reinforcing political hierarchies and economic dependencies. Conversely, defeat could lead to significant political instability, with rival factions vying for power in the wake of a ruler's downfall.

Warfare also influenced cultural exchanges between city-states, as conquests often led to the assimilation of different practices, technologies, and artistic styles. The interplay of conflict and cooperation among city-states contributed to the rich tapestry of Maya culture and history, underscoring the complexity of their political interactions.

Legacy and Influence of Maya Political Structures

The political structures of the Maya civilization have left an enduring legacy that continues to influence the region today. The complexities of governance, social organization, and intercity relationships provide valuable insights into the development of political systems in Central America.

Modern Implications in Central America

The legacy of Maya political structures can be observed in contemporary Central American societies, where the historical influence of the Maya continues to shape cultural identities and political dynamics. The concept of city-states and decentralized governance has parallels in modern political arrangements, where local governance structures often reflect historical traditions.

Moreover, the social hierarchies established during the Maya period can still be seen today, with indigenous populations advocating for rights and representation in national politics. The historical context of the Maya civilization provides crucial insights into contemporary issues of governance, identity, and cultural heritage in the region.

The Study of Maya Governance in Contemporary Research

Contemporary research on Maya governance continues to evolve, incorporating interdisciplinary approaches that draw from archaeology, anthropology, history, and political science. Scholars are increasingly interested in understanding the complexities of Maya political systems, examining how they were shaped by various factors including environment, resource management, and social organization.

Research efforts have highlighted the importance of collaboration between disciplines to create a comprehensive understanding of Maya political structures. The study of ancient Maya governance not only enriches our knowledge of past societies but also informs discussions on governance, sustainability, and community organization in today's world.

Key Characteristics of Maya City-States

The Maya civilization, one of the most sophisticated and enduring cultures in pre-Columbian America, was distinguished by its complex political organization, represented in a network of city-states. These city-states, known as "polities," were characterized by unique features that governed their social, political, and economic interactions. Understanding these characteristics provides insight into the intricacies of Maya society and its enduring legacy.

Geography and Urban Planning

The geographical landscape of the Maya civilization played a crucial role in shaping the development and organization of its city-states. The civilization thrived in the dense jungles of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. This region, with its varied topography, including mountains, valleys, and coastal plains, influenced settlement patterns and urban planning.

- Urban Centers: Major city-states such as Tikal, Calakmul, Palenque, and Copán were strategically located near rivers and fertile land, facilitating agriculture and trade. Urban centers were often constructed with monumental architecture, including pyramids, palaces, and temples, which served both religious and political functions.

- City Layout: The layout of these cities was often centered around a large plaza, which served as a focal point for social and political activities. Surrounding the plaza were important structures such as the ball courts, administrative buildings, and elite residences, reflecting the hierarchical nature of Maya society.

- Environmental Adaptation: The Maya developed advanced agricultural techniques, including terracing and slash-and-burn farming, to adapt to their environment. These practices allowed them to sustain large populations and support the growth of their city-states.

The integration of natural resources, urban planning, and social organization contributed to the resilience and longevity of the Maya city-states. Their ability to adapt to and manipulate their environment was a testament to their ingenuity and resourcefulness.

Social Hierarchy and Governance

The social structure of the Maya civilization was hierarchical, with a clearly defined class system that influenced governance and political dynamics within city-states. At the top of the social hierarchy were the elite classes, including the ruling dynasties and noble families, followed by priests, artisans, and commoners.

- Ruling Class: The political power was concentrated in the hands of a small number of elite families, often linked by blood ties and marriage alliances. The king, known as the "Ajaw," was considered semi-divine and held both secular and religious authority.

- Council of Nobles: The Ajaw was supported by a council of nobles, who assisted in governance and decision-making processes. This council often included high-ranking officials, military leaders, and priests, reflecting the intertwining of political and religious authority.

- Commoners and Laborers: The majority of the population consisted of commoners, who engaged in agriculture, trade, and craft production. While they had limited political power, they played a crucial role in the economy and supported the elite through tribute and labor.

Governance in Maya city-states was characterized by a combination of hereditary rule and political alliances. The ruling class often relied on patronage and kinship ties to maintain control and legitimacy. Political decisions were frequently influenced by religious beliefs, with the Ajaw serving as an intermediary between the gods and the people.

Economic Systems and Trade

The economic foundation of Maya city-states was primarily agrarian, supported by a complex system of trade and tribute. The agricultural practices of the Maya were diverse and sophisticated, allowing them to cultivate a variety of crops, including maize, beans, squash, and cacao.

- Agricultural Innovation: The Maya employed advanced agricultural techniques, such as raised-field agriculture and irrigation systems. These innovations helped maximize crop yields and sustain large populations.

- Trade Networks: Trade was a vital component of the Maya economy, connecting city-states with each other and with distant regions. Goods such as textiles, ceramics, jade, and obsidian were exchanged, with cacao being a significant trade item used as currency in some areas.

- Tribute Systems: The city-states often extracted tribute from subordinate communities, which included agricultural products, labor, and material goods. This tribute system reinforced the power of the ruling elite and facilitated the maintenance of political control.

The economic systems of the Maya city-states were intricately connected to their political structures. Control over resources and trade routes was essential for maintaining power and influence, leading to both cooperation and conflict among city-states.

In summary, the key characteristics of Maya city-states reflect a complex interplay of geography, social hierarchy, and economic systems. The strategic placement of urban centers, the hierarchical organization of society, and the sophistication of their economic practices contributed to the development of a rich and enduring civilization that continues to intrigue scholars and historians today.

Influential Dynasties in Maya History

The Maya civilization, renowned for its rich cultural heritage, remarkable achievements in various fields, and intricate political structures, was governed by a series of influential dynasties. These dynasties played a crucial role in shaping the political landscape of the Maya world, influencing everything from warfare to social structures. This section will delve into the significant dynasties that defined the era, focusing on the Kaan Dynasty, the rivalry between Tikal and Calakmul, and the role of women in power.

The Kaan Dynasty

The Kaan Dynasty, also known as the Snake Dynasty, was one of the most powerful and influential ruling families in Maya history, prominent particularly during the Late Classic period. This dynasty was centered in the city of Calakmul, which became a significant political and military force in the southern Maya lowlands. The Kaan Dynasty is noted for its aggressive expansionist policies and complex political maneuvers that allowed it to dominate its rivals.

One of the most notable rulers of the Kaan Dynasty was Yaxnuun Ahiin I, who ascended to the throne in the 6th century. His reign marked a period of significant territorial expansion and consolidation of power. The dynasty's rulers often engaged in warfare against neighboring city-states, particularly Tikal, which was one of the Kaan Dynasty's most formidable opponents. The strategies employed by the Kaan Dynasty included forming alliances with other city-states and utilizing their military prowess to assert dominance.

The Kaan Dynasty's influence extended beyond mere territorial control; it also established a complex network of alliances and vassal states. This network allowed Calakmul to exert control over a significant portion of the Maya lowlands, facilitating trade and cultural exchange. The rulers of the Kaan Dynasty were known to engage in extensive trade networks, which included the exchange of goods such as jade, obsidian, and cacao, enhancing their wealth and power.

Interestingly, the Kaan Dynasty's legacy is preserved in the numerous stelae and monuments that commemorate their rulers and significant events. These artifacts provide valuable insights into the political and social dynamics of the time, including the importance of lineage and divine right in legitimizing their rule.

The Tikal and Calakmul Rivalry

The rivalry between Tikal and Calakmul is one of the most documented and significant conflicts in Maya history. Tikal, located in modern-day Guatemala, was one of the largest and most powerful city-states of the Maya civilization. Its wealth was derived from its strategic location along trade routes, and it was known for its monumental architecture and cultural achievements. In contrast, Calakmul, ruled by the Kaan Dynasty, was a formidable rival that sought to challenge Tikal's supremacy.

This rivalry was characterized by a series of military conflicts, political maneuvering, and shifting alliances. The most notable conflict occurred during the late 7th century, when Tikal faced a series of defeats at the hands of Calakmul, leading to a significant shift in power dynamics in the region. The two city-states were engaged in a constant struggle for dominance, with each seeking to outmaneuver the other through warfare and diplomacy.

The Tikal-Calakmul rivalry is also significant for its impact on the broader geopolitical landscape of the Maya civilization. The conflicts between these two city-states often drew in other city-states, leading to a complex web of alliances and enmities. This interconnectedness illustrates the importance of warfare in shaping political relations among the Maya, highlighting how conflicts could alter the balance of power across vast regions.

A notable event in this rivalry was the capture of Tikal's ruler, Chak Tok Ich'aak I, by the forces of Calakmul in 695 AD. This event marked a turning point in the conflict and allowed Calakmul to exert greater influence over the region. The aftermath of this conflict saw Tikal's power decline, while Calakmul reached the zenith of its influence.

The Role of Women in Power

While the political structures of the Maya civilization were predominantly patriarchal, women played a crucial role in governance and the preservation of dynastic power. Female members of the ruling elite often held significant influence, especially in times of political instability or succession crises. The presence of powerful queens and regents in Maya history illustrates the complexities of gender roles within the political sphere.

One of the most notable examples of a powerful Maya queen is Lady Six Sky of Dos Pilas, who ruled in the late Classic period. She was instrumental in maintaining the power of her dynasty and was known for her political acumen and military strategies. Her reign exemplifies how women could navigate the male-dominated political landscape, wielding power effectively and influencing the course of events in their city-states.

Women were often portrayed in art and inscriptions as key figures in the royal lineage, emphasizing their importance in the continuation of dynastic power. Royal women frequently acted as intermediaries in political alliances, facilitating marriages and negotiations that strengthened ties between city-states. Their roles extended beyond mere consorts; they were often depicted as active participants in rituals and governance, highlighting their integral position in the political hierarchy.

The presence of female rulers and influential women in the Maya political landscape challenges the perception of a strictly patriarchal society. It indicates a more nuanced understanding of power dynamics, where women could exert significant influence and actively participate in governance.

Religious and Ceremonial Aspects of Governance

The political structure of the ancient Maya civilization was deeply intertwined with religious and ceremonial practices. Rulers were not only political leaders but also religious figures who played a crucial role in maintaining the cosmic order through ritualistic observances and ceremonies. This symbiosis between religion and governance shaped the social fabric of Maya society and influenced the political dynamics of their city-states.

The Connection Between Religion and Politics

In the Maya worldview, the universe was a complex interplay of natural and supernatural forces. Rulers, often considered divine or semi-divine, were seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people. This belief bestowed upon them the authority to govern and the responsibility to ensure harmony within their city-states. The political legitimacy of a ruler was frequently linked to their perceived ability to communicate with the divine and perform the necessary rituals to appease the gods.

Religious practices in the Maya civilization encompassed a wide range of ceremonies, including offerings, bloodletting, and elaborate festivals. These rituals were crucial for agricultural fertility, health, and general prosperity. The connection between religion and politics was evident in the construction of temples and ceremonial centers, which served both as places of worship and as political hubs where rulers conducted important state affairs. The alignment of political power with religious authority allowed rulers to maintain control over their subjects, as the populace believed that their welfare was directly tied to the actions and decisions of their leaders.

For instance, the annual cycle of religious festivals and rituals was essential for the political calendar. These events not only reinforced the ruler's status but also provided a platform for displaying power and wealth. The Maya engaged in public ceremonies, which often included the participation of nobles and commoners alike, fostering a collective identity among the populace. Such gatherings were vital for social cohesion and served as a reminder of the rulers' divine right to govern.

Rituals and Their Political Significance

The rituals performed by the Maya were intricately tied to their political systems and held significant political implications. Bloodletting ceremonies, for example, were common among the Maya elite, including rulers and nobility. These acts of self-sacrifice were believed to invoke the favor of the gods and were often performed before important political decisions or military actions. The shedding of blood was seen as a means to nourish the gods and maintain the balance of the universe, thus ensuring the continued prosperity of the city-state.

Additionally, the Maya celebrated various key events through elaborate ceremonial activities, such as the end of a k’atun (a 20-year cycle in the Maya calendar) or the accession of a new ruler. These ceremonies were not only religious observances but also political spectacles that reinforced the legitimacy of the ruling dynasty. The display of wealth and power during these events served to solidify alliances, intimidate rivals, and rally support among the populace.

The political significance of rituals extended beyond mere symbolism; they often involved the redistribution of resources and wealth. Feasts and communal gatherings provided opportunities for elites to demonstrate their generosity, thus reinforcing their status and authority. Such practices were vital for maintaining social order and ensuring loyalty among subjects, as the populace would be more likely to support a ruler who visibly contributed to their well-being through these communal events.

Moreover, the construction of monumental architecture, such as pyramids and temples, played a critical role in the interrelation of religion and politics. These structures served as both places of worship and political centers, where rituals were performed and power was displayed. The alignment of these buildings with astronomical events further emphasized the Maya's sophisticated understanding of time and cosmology, which was integral to their political narrative. Rulers often commissioned grand constructions to commemorate their achievements and divine mandate, thereby reinforcing their position within the cosmic order.

In conclusion, the religious and ceremonial aspects of governance in the Maya civilization were fundamental to understanding their political dynamics. The intertwining of religious authority and political power created a unique system where rulers governed not only through military strength but also through spiritual legitimacy. This complex relationship shaped Maya society, influencing everything from daily life to the overarching political landscape of their city-states.

Impact of Warfare on Political Dynamics

The Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in architecture, mathematics, and astronomy, was equally defined by its complex political landscape, significantly influenced by warfare. The dynamics of conflict not only shaped the relationships between various city-states but also altered the internal structures of power and governance. This section delves into two key aspects of this theme: military strategies and alliances, alongside the consequences of conflict on city-state relations.

Military Strategies and Alliances

The Maya employed a variety of military strategies, which were essential for the expansion and defense of their city-states. Unlike the typical notions of standing armies found in other ancient civilizations, the Maya often relied on a more flexible and ad-hoc military structure. Warfare was frequently characterized by the mobilization of warriors drawn from the local populace, organized under the leadership of elite nobles or rulers. This decentralized approach allowed for rapid responses to threats and opportunities, as city-states could quickly gather forces for defense or conquest.

One significant strategy employed by the Maya was the use of surprise attacks and ambush tactics. The dense jungles of the Yucatán Peninsula provided ample cover for these operations. The Maya were adept at utilizing their knowledge of the terrain to conduct raids on neighboring city-states, exploiting weaknesses and targeting specific resources or political figures. For instance, the city-state of Tikal frequently engaged in warfare with its rivals, employing guerrilla tactics that capitalized on the element of surprise.

Alliances also played a crucial role in Maya warfare. City-states often formed strategic partnerships with one another to bolster their military might. These alliances could be temporary, forged in response to immediate threats, or more permanent agreements aimed at mutual benefit. A notable example would be the alliance between Tikal and its neighboring city-states against common enemies, like Calakmul. Such coalitions were often solidified through marriage alliances between ruling families, thus intertwining political power with familial ties.

The complexity of these alliances and rivalries is illustrated by the famous conflict between Tikal and Calakmul, which was not merely a military struggle but a protracted series of political maneuvers, betrayals, and shifting allegiances. The use of diplomacy, alongside open conflict, was a hallmark of Maya political strategy, as leaders sought to maintain a balance of power within the region.

Consequences of Conflict on City-State Relations

The impact of military conflict on the political landscape of the Maya was profound and far-reaching. The outcomes of warfare could lead to significant territorial expansion for victorious city-states, but they also had the potential to destabilize the political equilibrium of the region. For instance, the defeat of a prominent city-state often resulted in the subjugation of its elites, who could be replaced by rulers from the victorious city-state, thereby altering the political hierarchy.

Moreover, warfare often resulted in the redistribution of resources, which could enhance the power of some city-states while crippling others. The spoils of war, including captured slaves, tribute, and access to vital trade routes, were critical for maintaining the economic strength of a city-state. This economic advantage could further enable the victors to invest in infrastructure, such as temples and public works, solidifying their dominance and influence in the region.

However, the repercussions of warfare were not solely beneficial for the victors. Prolonged conflicts could weaken both the aggressor and the defender, leading to political fragmentation and instability. The constant state of warfare necessitated a heavy toll on the population, leading to social unrest and diminishing returns in agriculture and trade. The classic Maya collapse, often attributed to various factors, including environmental degradation and drought, was exacerbated by the strains of continuous warfare and political conflict among city-states.

Additionally, warfare fostered a culture of violence that permeated Maya society. The glorification of military achievements was evident in art and inscriptions, where victories were celebrated, and defeated enemies were displayed as trophies. This cultural endorsement of warfare influenced the political aspirations of rulers, as military success became a key aspect of legitimacy and authority within Maya governance.

In summary, the interplay between warfare and political dynamics in the Maya civilization was intricate, marked by evolving strategies, shifting alliances, and significant consequences for city-state relations. The lens of military conflict provides profound insights into the governance and societal structures of the Maya, highlighting how the pursuit of power and survival shaped their historical trajectory.

Legacy and Influence of Maya Political Structures

The political structures of the ancient Maya civilization have left a profound legacy that continues to influence Central America and the field of anthropology today. The complexities of their governance, social hierarchy, and urban planning are not merely relics of the past but are relevant to understanding the contemporary socio-political landscape in the region. This section delves into the modern implications of Maya political structures and the ongoing study of Maya governance in contemporary research.

Modern Implications in Central America

The political legacy of the Maya civilization manifests in various ways across Central America. Countries such as Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and Mexico continue to grapple with issues that can be traced back to the political organization of ancient city-states. The fragmentation of power that characterized Maya governance is echoed today in the decentralized political systems that often lead to regional disparities in wealth, education, and governance.

One significant aspect of the legacy is the preservation of indigenous identity among the Maya descendants. Despite centuries of colonization and cultural assimilation, many contemporary Maya communities maintain their unique cultural practices, languages, and governance structures. The traditional systems of governance, often rooted in communal decision-making and consensus, can be seen in the governance of modern indigenous communities, which advocate for their rights and seek autonomy within the national political framework.

Furthermore, the historical significance of city-states has influenced modern political boundaries and governance. The ancient competition and alliances among city-states set a precedent for territorial disputes and regional cooperation, which are still evident in Central America today. Issues such as land rights, resource management, and environmental conservation are often framed within this historical context, influencing how communities negotiate their relationships with national governments and multinational corporations.

The Maya's legacy is also visible in the political movements that advocate for indigenous rights and environmental sustainability. Organizations like the Indigenous Peoples' Council have arisen in response to the historical injustices faced by indigenous groups, drawing on the governance practices of their ancestors to argue for greater representation and respect for their traditions.

The Study of Maya Governance in Contemporary Research

The academic study of Maya political systems has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians have increasingly recognized the importance of understanding the political dynamics of the Maya as a means to comprehend broader themes of governance, power, and social organization in ancient societies. This research has been aided by advances in technology, such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), which has allowed for the discovery of previously hidden structures and urban layouts that provide insights into Maya political organization.

Contemporary research emphasizes the need to view Maya governance through a multi-disciplinary lens, incorporating perspectives from archaeology, ethnohistory, and anthropology. Scholars now focus on understanding the interactions between different city-states, their political alliances, and the socio-economic factors that influenced their rise and fall. This comprehensive approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of Maya society, challenging earlier simplistic narratives that portrayed them solely as warlike or hierarchically structured.

Furthermore, there is a growing interest in examining the role of women in Maya governance, which has historically been overlooked. Recent studies have highlighted the influence of royal women, their roles in dynastic politics, and how gender dynamics shaped governance in Maya society. This shift in focus not only enriches the historical narrative of the Maya but also reflects broader trends in contemporary scholarship that seeks to include diverse voices and experiences in the study of history.

In addition to traditional academic research, there is also a vibrant field of public archaeology that seeks to engage local communities in the interpretation of their heritage. This approach recognizes the importance of indigenous knowledge and perspectives, fostering a dialogue between scholars and Maya descendants. Such collaborations can lead to a deeper understanding of how ancient political systems can inform contemporary governance and community resilience.

Comparative Studies and Global Contexts

The legacy of the Maya political structure has implications that extend beyond Central America, allowing for comparative studies with other ancient civilizations. Scholars have begun to draw parallels between Maya governance and that of other civilizations, such as the city-states of Mesopotamia, the city-states of ancient Greece, and the urban centers of the Indus Valley. These comparisons help to situate the Maya within a broader context of human political development, highlighting both unique characteristics and common themes across different cultures.

One area of interest is the concept of city-states as a form of governance. The decentralized political organization of the Maya, with its numerous city-states each functioning independently yet interconnected through trade and diplomacy, invites comparisons to similar political structures in other ancient societies. This comparative approach can yield insights into how geographical, environmental, and social factors influenced political organization and state formation across different cultures.

Moreover, the ancient Maya's approach to governance also informs contemporary discussions about sustainability and ecological management. The Maya's intricate understanding of their environment, as evidenced by their agricultural practices and urban planning, can serve as valuable lessons for modern societies grappling with issues of climate change, resource depletion, and sustainable development. By studying the successes and failures of ancient political systems, contemporary leaders can draw on historical precedents to inform present-day governance and policy-making.

Statistical Insights into Maya Legacy

| Aspect | Modern Relevance | Statistical Data |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Population | Preservation of culture and identity | Approximately 6 million Maya descendants in Central America |

| Land Rights | Ongoing disputes and advocacy for autonomy | Over 50% of indigenous communities face land conflicts |

| Environmental Practices | Influence on sustainable agriculture | Increases in organic farming practices among indigenous communities |

| Academic Research | Interdisciplinary studies of governance | Increased publications on Maya political structures in the last decade |

In conclusion, the political structures of the ancient Maya civilization have left an indelible mark on the cultural and political landscape of Central America and beyond. Their legacy continues to shape the identity, governance, and social dynamics of contemporary Maya communities, while also providing valuable insights for academic research and global discussions on governance and sustainability.