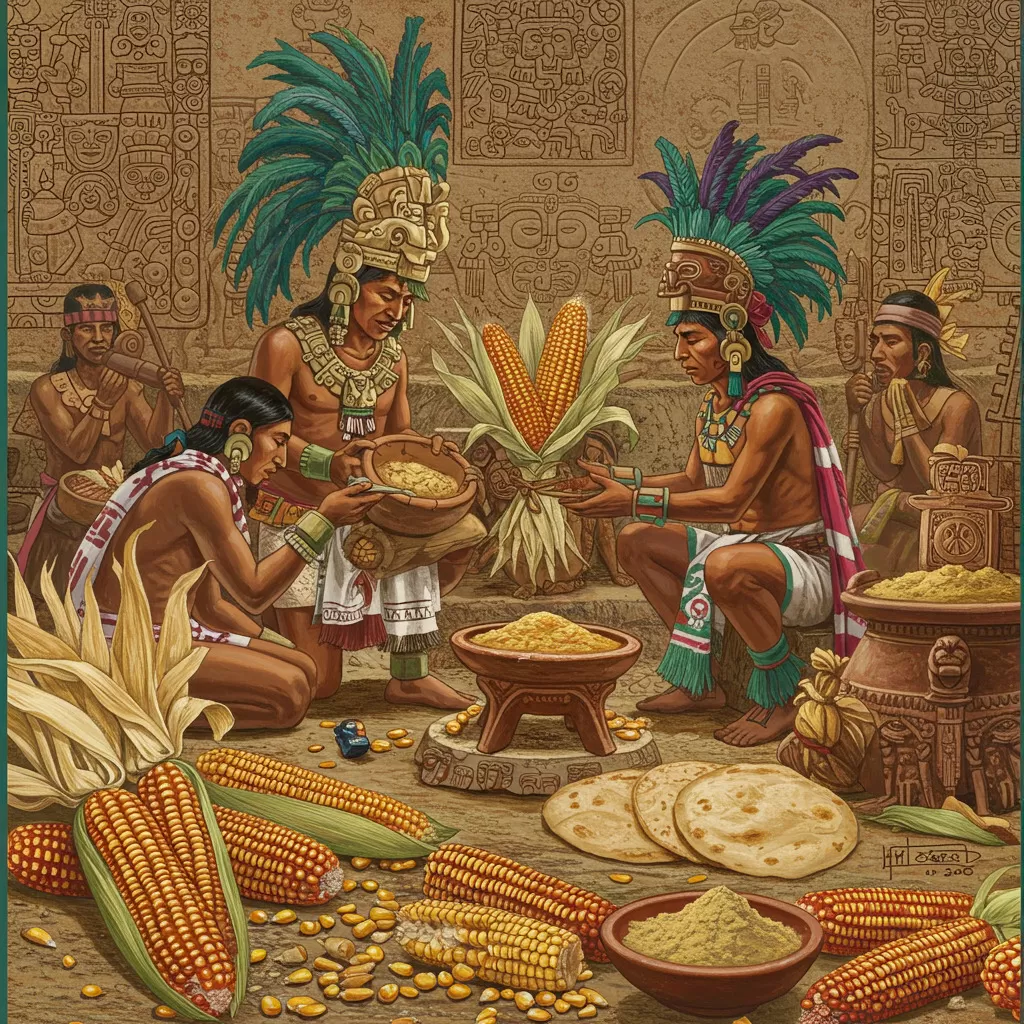

The Importance of Corn in Maya Culture

Corn, or maize, holds a place of unparalleled significance in the culture of the Maya civilization, serving as more than just a staple food. For the ancient Maya, corn was the very essence of life, intricately woven into their mythology, daily practices, and social structures. From the moment of its cultivation, corn has shaped their agricultural practices and culinary traditions, sustaining communities for centuries and influencing their identity.

The reverence for corn among the Maya is deeply rooted in their history and spirituality. Myths and legends abound, depicting corn as a gift from the gods, embodying both sustenance and sacredness. This article will explore the multifaceted role of corn in Maya culture, shedding light on its historical significance, culinary applications, and the profound religious and ceremonial practices that celebrate this vital crop.

Historical Significance of Corn in Maya Culture

Corn, or maize, holds a pivotal position in the historical narrative of the Maya civilization, symbolizing not just a staple food source but also a deep cultural and spiritual significance. The origins of corn cultivation can be traced back thousands of years, making it one of the earliest domesticated crops in the Americas. The profound relationship between the Maya people and corn is reflected in their agricultural practices, social structures, and religious beliefs.

Origins and Early Cultivation

The origins of corn can be traced back to a wild grass known as teosinte, which was domesticated by Mesoamerican societies around 9000 years ago. Archaeological evidence suggests that the domestication of corn occurred in southern Mexico, and by the time the Maya civilization emerged around 250 CE, corn had become a central component of their diet and economy. The process of domesticating teosinte into the corn we know today took thousands of years, involving selective breeding to enhance desirable traits such as size and yield.

The Maya developed sophisticated agricultural techniques to cultivate corn, including slash-and-burn methods and raised-field agriculture. These practices not only provided a reliable food source but also allowed for the cultivation of other crops such as beans and squash, creating a triad known as the "Mesoamerican triad," which formed the basis of the Maya diet. Corn was planted in the milpas, or shifting fields, and required careful management of soil fertility and water resources, demonstrating the Maya's advanced understanding of their environment.

Corn was not merely a food source; it was a symbol of life and sustenance, deeply ingrained in the social fabric of Maya society. The labor-intensive cultivation process fostered community cooperation, with families and neighbors coming together to plant and harvest crops. This collective effort reinforced social bonds and established a sense of identity centered around corn cultivation. The Maya believed that their agricultural success was tied to their relationship with the gods, further intertwining their spiritual beliefs with the act of farming.

Myths and Legends Surrounding Corn

The mythology of the Maya is rich with tales that emphasize the importance of corn. One of the most significant narratives is that of the Hero Twins, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, who exemplify the theme of resurrection and rebirth. According to the Popol Vuh, the Maya creation story, the gods decided to create humans who could worship them properly. After several failed attempts, they created humans from corn, giving them life and the ability to speak. This myth underscores the belief that corn is the essence of life itself, a divine gift that connects the Maya people to their gods.

In addition to the creation myths, corn figures prominently in various rituals and ceremonies. The Maya believed that corn had its own spirit, and they honored this spirit through offerings and ceremonies aimed at ensuring a bountiful harvest. During agricultural festivals, such as the “Festival of the New Corn,” the Maya would conduct elaborate rituals, including the preparation of special dishes made from fresh corn, to express gratitude to the gods and seek their blessings for the upcoming planting season.

The connection between corn and the divine is further illustrated in the depictions found in Maya art and hieroglyphics. Corn deities, such as the Maize God, are frequently represented in murals, pottery, and stelae, symbolizing fertility, sustenance, and the cycle of life and death. The prominence of corn in these artistic expressions reflects its central role in the Maya worldview, where the physical and spiritual realms were inextricably linked.

In summary, the historical significance of corn in Maya culture extends beyond its role as a staple food. It is a symbol of life, community, and spirituality, deeply woven into the fabric of their society. The Maya's advanced agricultural practices and rich mythology surrounding corn highlight their understanding of the natural world and their reverence for the divine forces that influenced their existence. Through the cultivation and celebration of corn, the Maya not only sustained their physical bodies but also nurtured their cultural identity and spiritual beliefs.

Culinary Uses of Corn in Maya Society

Corn, or maize, is not only a staple food in Maya culture but also a central element that shapes the culinary landscape of their society. The significance of corn extends far beyond mere sustenance; it embodies cultural identity, agricultural practices, and social traditions. The culinary uses of corn in Maya society are vast and varied, encompassing traditional dishes, preparation methods, and the essential role it plays in daily nutrition. This section will explore the incredible versatility of corn in Maya cuisine, highlighting its importance as a nourishing food source and its deep-rooted presence in everyday life.

Traditional Dishes and Preparation Methods

In Maya society, corn is the foundation of many traditional dishes, reflecting the agricultural heritage and culinary ingenuity of the Maya people. The versatility of corn allows it to be transformed into a wide array of foods, each with its unique preparation methods and cultural significance. Some of the most notable traditional dishes include tortillas, tamales, and atole.

Tortillas are perhaps the most iconic corn-based food in Maya cuisine. They are made from masa, a dough derived from nixtamalized corn, which involves soaking the kernels in an alkaline solution, typically limewater. This process not only enhances the nutritional value of the corn by increasing calcium levels but also improves its flavor and digestibility. Tortillas serve as a staple in daily meals and are used to accompany almost every dish, from stews to grilled meats. The process of making tortillas is often communal, with families gathering to prepare them together, reinforcing social bonds within the community.

Tamales are another beloved dish that exemplifies the culinary creativity of the Maya. Made from masa and filled with various ingredients such as meats, vegetables, or fruits, tamales are wrapped in corn husks and steamed to perfection. This dish showcases the adaptability of corn, as it can be combined with a variety of fillings, reflecting regional flavors and personal preferences. Tamales are often prepared for special occasions and celebrations, emphasizing their role in communal and family gatherings.

Atole, a warm and comforting beverage, is another traditional use of corn. Made from masa mixed with water or milk, atole is often flavored with spices or sweeteners such as cinnamon, chocolate, or sugar. This drink is particularly popular during festive seasons and is frequently served alongside tamales or other corn-based dishes. Atole not only nourishes the body but also serves as a reminder of the rich agricultural heritage of the Maya people, as it showcases the importance of corn in their daily lives.

The preparation methods for corn-based dishes are deeply rooted in tradition and often involve age-old techniques passed down through generations. The use of grinding stones, called metate and mano, to prepare masa is an art form that requires skill and patience. This traditional practice not only preserves the flavors of the corn but also connects the cooks to their ancestors, reinforcing cultural identity and continuity.

Importance of Corn in Daily Nutrition

In Maya society, corn plays a crucial role in daily nutrition, providing essential carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Corn is a primary source of energy, making it an integral part of the Maya diet. The consumption of corn-based foods ensures that families receive the necessary nutrients to sustain their daily activities, from agricultural labor to communal gatherings.

The nutritional profile of corn is enhanced through traditional preparation methods like nixtamalization. This process not only increases the bioavailability of niacin, a vital B vitamin, but also enriches the corn with calcium, an essential mineral for bone health. The incorporation of corn into various dishes ensures that the Maya people receive a balanced diet, with corn serving as a primary staple complemented by other food sources such as beans, squash, and fruits.

Beans, often referred to as the "meat of the poor," are commonly consumed alongside corn, creating a complete protein source. This combination, known as the "Maya triad," is fundamental to the Maya diet, offering a well-rounded nutritional profile. The interdependence of corn and beans not only reflects the agricultural practices of the Maya but also highlights their understanding of nutrition and health.

Moreover, corn is deeply integrated into social and cultural aspects of Maya life, further emphasizing its importance in daily nutrition. Families often gather to share meals centered around corn-based dishes, reinforcing communal ties and fostering a sense of belonging. Festivals and rituals often feature corn as a central element, showcasing its significance beyond mere sustenance and highlighting its role as a cultural symbol.

In addition to its nutritional value, corn is also a versatile ingredient that allows for a diverse range of culinary expressions. Different regions of the Maya world have developed unique corn-based dishes, reflecting local ingredients, flavors, and cooking techniques. This diversity in preparation methods not only enriches the culinary landscape but also underscores the adaptability of corn as a food source.

The importance of corn in Maya cuisine cannot be overstated. It is not only a source of nourishment but also a symbol of cultural identity, agricultural practices, and social connections. The culinary uses of corn in Maya society reflect a deep-rooted relationship with the land and a profound understanding of nutrition and health. Through traditional dishes and preparation methods, corn continues to play a vital role in the daily lives of the Maya people, preserving their heritage and shaping their culinary traditions.

In conclusion, the culinary uses of corn in Maya society are a testament to the creativity and resilience of the Maya people. From tortillas to tamales and atole, corn serves as a foundation for a rich and diverse culinary landscape. Its importance in daily nutrition further reinforces its status as a cultural symbol, showcasing the deep connections between food, identity, and community in Maya culture.

Corn in Maya Religious and Ceremonial Practices

Corn, or maize, is not merely a staple food in Maya culture; it is an integral part of their spiritual and ceremonial life. The significance of corn in Maya religious practices transcends its nutritional value, embodying the connection between the people, their environment, and their gods. For the ancient Maya, corn was a gift from the deities, and it played a pivotal role in various rituals and ceremonies that aimed to honor these divine beings and ensure agricultural prosperity.

Rituals Involving Corn

The rituals involving corn were diverse and often tied to the agricultural calendar. The Maya practiced a form of animism, wherein they believed that spirits inhabited all elements of nature, including crops. As such, the cultivation and harvesting of corn were surrounded by rituals designed to show respect and gratitude to these spirits and deities.

One of the most significant agricultural ceremonies was the “Ritual of the New Corn”, celebrated at the onset of the new harvest season. This ceremony involved the planting of the first seeds of corn, which were often accompanied by offerings of incense, flowers, and other food items to the gods. Such offerings were believed to ensure a bountiful harvest and to thank the deities for past blessings. The ceremony was not simply a mechanical act of planting; it was imbued with deep spiritual meaning and rituals that reinforced the community’s connection to the land and their gods.

Another important ritual was the “Harvest Ceremony”, which occurred when the corn was ripe for harvest. During this time, communities would gather to celebrate the fruits of their labor. In these ceremonies, corn was often used in various forms, from whole ears to ground corn in the form of tortillas or tamales. Community members would participate in prayers and dances, asking for the continued favor of the gods. Additionally, it was common to see the “Maya Ball Game” played during this time, where the game itself had deep symbolic ties to the cycles of life and death, much like the cycles of corn growth.

Even the act of consuming corn was ritualized. The first tortillas of the harvest were often offered to the gods before being consumed by the community. This act symbolized sharing the harvest with the divine, reinforcing the belief that their sustenance was tied intimately to spiritual forces.

Symbolism of Corn in Maya Beliefs

Corn was deeply symbolic in Maya cosmology, representing life, sustenance, and the cyclical nature of existence. The Maya believed that humans were created from maize, a myth reflected in various creation stories. According to the Pope of the Maya, the gods attempted to create humans from mud and then wood, but it was not until they used corn that they succeeded. This myth underscores the fundamental role of corn in not just agriculture, but in the very identity of the Maya people.

The significance of corn is further evidenced in the Maya calendar, which is closely aligned with agricultural cycles. The Tzolk’in calendar, consisting of 260 days, is believed to reflect the gestation period of maize. Each day in this calendar has its own significance, and many are associated with specific deities that governed aspects of corn cultivation. For instance, the god Ek’ Chua, who was associated with commerce and cacao, was also associated with maize, emphasizing the intertwining of agricultural and economic practices.

Corn also played a role in funerary practices. It was common for the Maya to include corn in burial offerings, reflecting the belief in its ability to sustain life beyond death. This practice highlights the duality of corn as both a life-giving force and a symbol of mortality, demonstrating the Maya’s understanding of the cycle of life.

The use of corn in rituals and as a symbol of life is further illustrated in the iconography found in Maya art and architecture. Numerous depictions of corn can be seen in carvings and murals throughout ancient Maya cities, often associated with deities such as Itzamná and Chac, who were believed to control rain and agriculture. Such representations served to reinforce the cultural belief that corn was a divine gift to humanity, further solidifying its place in their religious practices.

Corn in Creation Myths and Legends

The myths surrounding the origins of corn are rich and varied. One of the most prominent stories is that of the Popol Vuh, the sacred text of the K'iche' Maya. In this text, the gods, after multiple failed attempts to create humans from other materials, finally succeeded by using corn. This narrative emphasizes not only the importance of corn in the physical creation of humans but also its status as a divine and sacred element in Maya culture.

Legends about corn often highlight its transformative power. For instance, it is said that corn has the ability to bring forth life, prosperity, and abundance. The Maya believed that the health of their corn was directly linked to their own well-being. Thus, any blight or failure in the corn crop was seen as a sign of displeasure from the gods, leading to rituals aimed at appeasing the deities.

Moreover, the cyclical nature of corn growth aligns with the Maya’s understanding of time and existence. The planting and harvesting of corn mirror the cycles of life, death, and rebirth, reinforcing the spiritual significance of this crop. This belief is reflected in the various festivals and rituals that celebrate the agricultural calendar, marking the transitions between planting, growth, and harvest.

Community and Corn

In Maya society, corn was not only a source of sustenance but also a crucial element of social cohesion. The rituals surrounding corn often involved the entire community, fostering a sense of belonging and shared purpose. Festivals celebrating corn harvests were occasions for communal gathering, reinforcing social ties and cultural identity.

The act of preparing corn-based foods was also communal. Families would come together to grind corn, make tortillas, and prepare festive meals. These shared activities not only provided nourishment but also strengthened familial and community bonds. The social aspect of corn preparation and consumption emphasizes its role in Maya culture as a unifying force.

Furthermore, corn was integral to Maya trade and economy. The surplus of corn allowed for bartering and commerce, creating networks of exchange that connected various communities. This economic aspect further intertwined corn with the social fabric of Maya society, as it became a currency of value and a foundation for social interactions.

The Legacy of Corn in Maya Culture

The legacy of corn in Maya culture continues to resonate in contemporary societies. Many modern Maya communities still honor the ancient traditions surrounding corn through rituals and celebrations that reflect their deep connection to this vital crop. The importance of corn is evident in traditional dishes, agricultural practices, and communal gatherings, showcasing its enduring significance as a symbol of life and sustenance.

Today, efforts to preserve traditional agricultural practices and the cultural significance of corn are essential for maintaining the identity of Maya communities. Initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable farming practices and the importance of heirloom corn varieties highlight the ongoing relevance of corn in Maya culture.

In conclusion, corn in Maya religious and ceremonial practices is a profound testament to its importance beyond mere sustenance. As a symbol of life, community, and divine connection, corn continues to embody the essence of Maya culture, reflecting the intricate relationship between the people, their environment, and their beliefs.