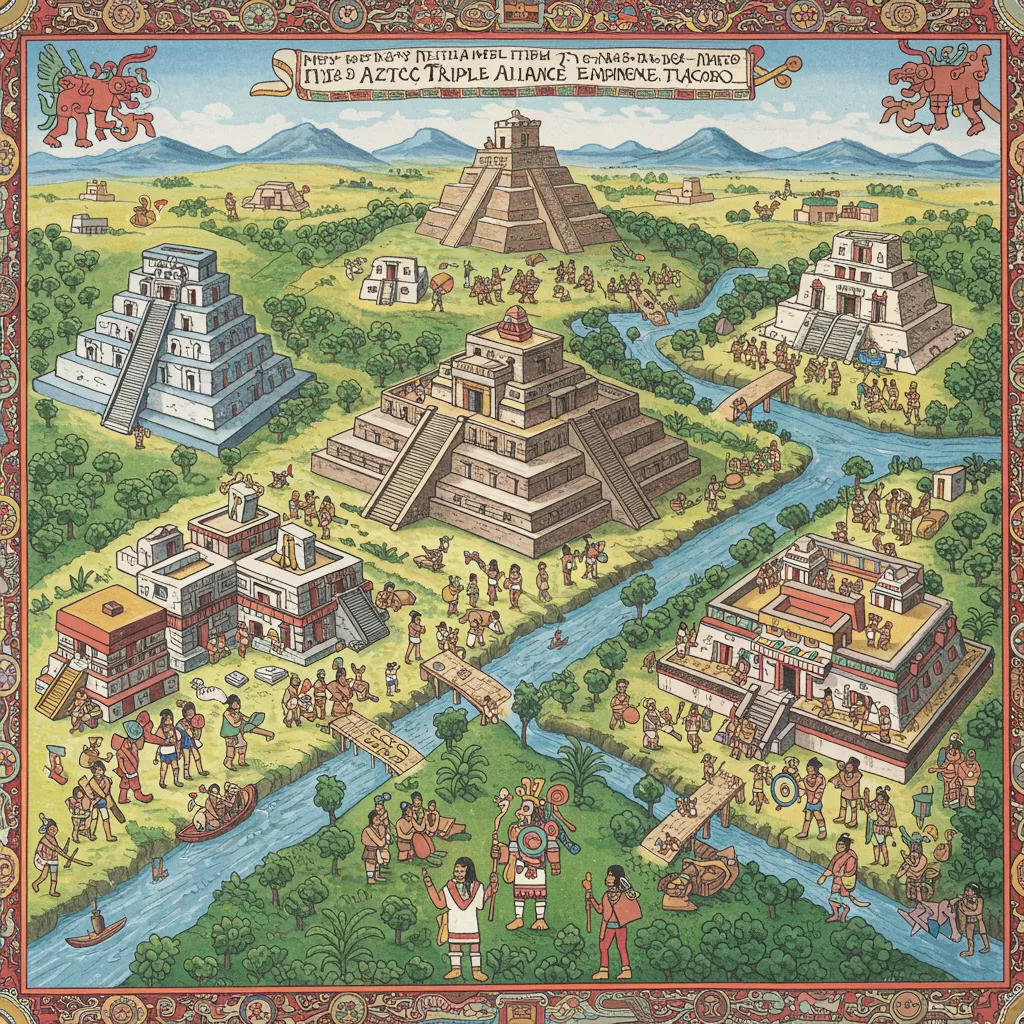

The Aztec Triple Alliance: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan

The Aztec Triple Alliance, a powerful coalition formed in the early 15th century, played a pivotal role in shaping the historical landscape of Mesoamerica. Comprising the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, this alliance not only marked the rise of the Aztec Empire but also established a formidable political and military presence that dominated the region for decades. Understanding the intricacies of this alliance reveals the complex interplay of power, culture, and economy that characterized Aztec society.

The formation of the Triple Alliance was not merely a strategic military maneuver; it was a reflection of the evolving relationships among these city-states. Each partner brought unique strengths and resources to the coalition, fostering a synergy that enabled them to expand their territories and influence. As we delve into the origins and dynamics of this alliance, we will uncover the significant historical figures involved, the major city-states that thrived under its banner, and the lasting impact of their combined legacies on future generations.

Historical Context of the Aztec Triple Alliance

The Aztec Triple Alliance, formed in the early 15th century, was a powerful political and military coalition that fundamentally altered the landscape of Mesoamerica. This alliance consisted of three central city-states: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. Understanding the historical context of the Aztec Triple Alliance involves exploring the origins of the Aztec Empire, the formation of the alliance itself, and the key historical figures who played a crucial role in its establishment and expansion. Each of these components provides insight into how the Aztecs emerged as a dominant force in the region and how their legacy continues to influence modern Mexico.

Origins of the Aztec Empire

The origins of the Aztec Empire can be traced back to the early 14th century. The Mexica, the indigenous people who later became known as the Aztecs, migrated to the Valley of Mexico from the north. According to oral traditions, they settled on an island in Lake Texcoco, where they founded Tenochtitlan in 1325. The location was strategically significant, providing access to natural resources, fertile land, and a defensive position against potential invaders.

Initially, the Mexica were a nomadic tribe, often marginalized and forced into servitude by the more established city-states in the region. However, through a combination of military prowess, strategic alliances, and a unique religious belief system, they began to rise in power. The Mexica saw themselves as chosen people, destined to create a great empire. This belief was fueled by their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli, who guided them to their new homeland. The growing population of Tenochtitlan, coupled with their aggressive expansionist policies, set the stage for the eventual formation of the Triple Alliance.

By the late 14th century, the Mexica began to expand their territory, engaging in warfare against rival city-states such as Azcapotzalco, Culhuacan, and Coatepec. These early conquests were not merely for land, but also for captives, who were essential for religious sacrifices, a critical aspect of Aztec culture. The wealth generated from these conquests allowed for the construction of monumental architecture, such as temples and palaces, and the establishment of a complex social hierarchy.

Formation of the Triple Alliance

The formal establishment of the Triple Alliance occurred around 1428, a pivotal moment in Aztec history. The Mexica, under the leadership of Itzcali, sought to consolidate power by forming strategic alliances with neighboring city-states. The alliance was initially formed with Texcoco and Tlacopan, both of which were key players in the region.

Texcoco, ruled by the charismatic leader Nezahualcoyotl, was an important cultural and political entity in its own right. Nezahualcoyotl was a philosopher and poet, and his reign is often characterized by a flourishing of arts and sciences. Recognizing the potential benefits of an alliance, he allied with the Mexica, which allowed for a combined military force that was far more powerful than any single city-state could muster alone. This collaboration was not merely a political maneuver; it was a fusion of military strength, cultural exchange, and shared religious beliefs that would define the Aztec Empire.

Tlacopan, although smaller than the other two, played a critical role in the alliance. Its strategic location and resources complemented those of Tenochtitlan and Texcoco. The leadership of Tlacopan was eager to participate in the alliance, recognizing that the combined resources and military capabilities would provide security against powerful adversaries like the Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco. The alliance quickly proved to be a formidable force, leading to a series of successful campaigns against rival city-states.

One of the most significant battles in this period was the defeat of the Tepanecs, which solidified the power of the Triple Alliance and allowed it to exert dominance over much of central Mexico. The victory was not only a military triumph but also a symbolic one, showcasing the strength of unity among the three city-states. Following this victory, the Aztec Empire expanded rapidly, incorporating various city-states into its growing domain.

Key Historical Figures

The formation and expansion of the Aztec Triple Alliance were influenced by several key historical figures, whose leadership and vision were instrumental in shaping the course of Mesoamerican history.

Itzcali, the Mexica leader, was pivotal in orchestrating the alliance and laying the groundwork for the Aztec Empire's dominance. Known for his military acumen, he was instrumental in uniting the three city-states. His strategies in warfare and diplomacy helped elevate Tenochtitlan from a mere city-state to the heart of a burgeoning empire.

Nezahualcoyotl, the ruler of Texcoco, was not only a political ally but also a cultural icon. His reign marked a golden age for Texcoco, characterized by advancements in poetry, philosophy, and architecture. He is often remembered for his contributions to the arts and his efforts to promote a more enlightened governance model. Nezahualcoyotl's vision for a united Mesoamerica, where culture and religion could flourish, played a significant role in solidifying the alliance.

The ruler of Tlacopan, who remains less documented than his counterparts, was equally important in the political landscape of the Triple Alliance. His support and resources were vital, particularly in military campaigns against common foes. The leadership dynamics among these three figures established a collaborative governance model that allowed for shared power and mutual benefit, a rarity in the often tumultuous political climate of Mesoamerica.

In summary, the historical context of the Aztec Triple Alliance is a complex tapestry woven from the threads of migration, conquest, and cultural exchange. The Mexica's journey from a marginalized tribe in the Valley of Mexico to the architects of a powerful empire illustrates the significance of strategic alliances and the profound impact of key historical figures. The formation of the Triple Alliance not only transformed the political landscape of Mesoamerica but also laid the foundation for the rich cultural legacy that would define the Aztec civilization.

The Major City-States of the Alliance

The Aztec Triple Alliance, which comprised the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, played a pivotal role in the history of Mesoamerica, significantly shaping political, economic, and cultural landscapes. Each of these city-states had its own unique characteristics and contributions, which collectively contributed to the strength and influence of the alliance. This section will delve into the details of each major city-state, shedding light on their distinctive roles and significance within the Triple Alliance.

Tenochtitlan: The Capital City

Tenochtitlan was the heart of the Aztec Empire and served as the capital city of the alliance. Founded in 1325 on an island in Lake Texcoco, it emerged as a powerful urban center characterized by its impressive architecture, advanced agricultural practices, and complex societal structure. The city was founded on the prophecy of the Mexica people, who were guided by a vision of an eagle perched on a cactus devouring a serpent, symbolizing their destined place in the valley of Mexico.

At its peak, Tenochtitlan was one of the largest cities in the world, with estimates of its population ranging from 200,000 to 300,000 inhabitants. The city was meticulously planned, featuring a grid-like layout with canals that facilitated transportation and trade. The Templo Mayor, a grand temple dedicated to the gods Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, stood at the center, symbolizing the religious and cultural significance of the city.

Tenochtitlan's economy was largely based on agriculture, particularly the cultivation of maize, beans, and squash, which were grown using the innovative chinampa system. This method involved creating floating gardens that maximized agricultural output and helped sustain the growing population. Additionally, the city was a bustling trade hub, with marketplaces like Tlatelolco serving as a center for commerce where goods from all over Mesoamerica converged.

The political structure of Tenochtitlan was centered around a monarch, known as the huey tlatoani, who wielded significant power. Moctezuma II, one of the most notable rulers, expanded the empire’s boundaries and reinforced Tenochtitlan's position as a dominant force in the region. His reign was marked by military conquests that increased the empire's wealth and influence, leading to a complex tribute system where conquered territories were required to provide goods and resources.

Texcoco: The Cultural Hub

Texcoco, located on the eastern shore of Lake Texcoco, was renowned as a cultural and intellectual center within the Aztec Empire. Unlike Tenochtitlan, which was primarily focused on military might, Texcoco flourished as a bastion of arts, literature, and philosophy. The city was established prior to the formation of the Triple Alliance but became an integral part of it, serving as a crucial ally in both military and cultural endeavors.

The city's most famous ruler, Nezahualcoyotl, was a poet, philosopher, and statesman who reigned during the early 15th century. Under his leadership, Texcoco became a center for intellectual thought and artistic expression. Nezahualcoyotl’s court attracted scholars and artists, leading to significant advancements in poetry, music, and philosophy. He is often credited with the creation of the “Flower and Song” tradition, which emphasized the importance of beauty, art, and the transient nature of life.

Texcoco also played a vital role in the political dynamics of the Triple Alliance. The city-state acted as a mediator in conflicts and was essential in formulating strategies for military campaigns. Its strategic location allowed for effective communication and coordination among the allied city-states. Furthermore, Texcoco contributed to the economic strength of the alliance through its agricultural production and trade relations.

Texcoco is also notable for its advancements in engineering and architecture. The city featured intricate hydraulic systems, including canals and aqueducts, which provided fresh water to its inhabitants and supported agriculture. This engineering prowess exemplified the ingenuity of the Mexica civilization and its ability to adapt to its environment.

Tlacopan: The Strategic Partner

Tlacopan, also known as Tacuba, was the smallest of the three city-states but played a crucial role as a strategic partner within the Triple Alliance. Located to the west of Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan served as a military ally and provided essential resources that supported the alliance’s expansionist endeavors. Its significance was largely rooted in its geographical position, which allowed it to act as a buffer against rival city-states and to facilitate trade routes.

The city-state of Tlacopan was known for its skilled warriors and played a key role in military campaigns alongside Tenochtitlan and Texcoco. The alliance, formed in the early 15th century, was primarily a response to the growing threats from neighboring city-states, and Tlacopan’s military capabilities were instrumental in the successes achieved during this period. The collaboration between the three city-states enabled them to conquer vast territories and establish dominance over Mesoamerica.

Despite its smaller size, Tlacopan's influence in the alliance was significant, especially in terms of resource distribution. The city was rich in agricultural land, which allowed it to contribute to the alliance’s food supply. Additionally, Tlacopan served as a center for the production of goods such as textiles and pottery, which were critical for trade and tribute payments to Tenochtitlan. This economic interdependence solidified the bond between the city-states and ensured the stability of the alliance.

The political structure of Tlacopan was similar to that of Tenochtitlan and Texcoco, with a ruling elite that governed the city-state. The leadership often collaborated with the other city-states in decision-making processes, demonstrating the cooperative nature of the alliance. The rulers of Tlacopan, while subordinate to Tenochtitlan in terms of political hierarchy, maintained significant autonomy and played a vital role in the alliance’s governance.

Collaborative Dynamics within the Alliance

The relationship between Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan was characterized by a complex interplay of cooperation and competition. While each city-state maintained its own identity and governance, their collaboration was essential for the expansion and consolidation of power within the Aztec Empire. This dynamic resulted in a sophisticated political structure that allowed for effective decision-making and resource allocation.

The Triple Alliance was formalized through a series of treaties that outlined the responsibilities and benefits of each city-state. Tenochtitlan, as the dominant power, took the lead in military campaigns, while Texcoco contributed cultural and intellectual resources, and Tlacopan provided essential materials and manpower. This division of labor allowed the alliance to function efficiently and achieve remarkable successes in conquest and governance.

Moreover, the alliance facilitated a robust trade network that connected the three city-states and extended to other regions of Mesoamerica. The cities engaged in reciprocal trade, exchanging goods such as textiles, agricultural products, and luxury items. This economic collaboration not only strengthened their individual economies but also enhanced the overall prosperity of the alliance.

The cultural exchanges that occurred within the Triple Alliance were equally significant. The collaboration between Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan fostered a rich cultural environment where art, music, and literature flourished. Festivals and ceremonies were held that celebrated the shared heritage of the city-states, reinforcing their unity and collective identity.

Conclusion

The major city-states of the Aztec Triple Alliance—Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan—each played unique and vital roles in shaping the political, economic, and cultural landscape of the Aztec Empire. Tenochtitlan stood as the capital and military powerhouse, Texcoco emerged as a cultural and intellectual hub, while Tlacopan provided strategic military support and resources. Together, these city-states forged a powerful alliance that left an indelible mark on Mesoamerican history.

Through their collaborative dynamics, the Triple Alliance not only achieved remarkable military conquests but also fostered a vibrant cultural milieu that celebrated the richness of Aztec civilization. The legacy of these city-states continues to be felt today, as their contributions to art, poetry, and governance resonate throughout Mexican history.

Impact and Legacy of the Triple Alliance

The Aztec Triple Alliance, formed in the early 15th century, was one of the most significant socio-political unions in pre-Columbian America. Comprised of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, this alliance not only transformed the political landscape of Mesoamerica but also left a lasting impact on military, economic, and cultural fronts. In this section, we will explore the multifaceted legacy of the Triple Alliance, emphasizing its military expansions, economic systems, and cultural contributions.

Military Expansion and Conquests

The military prowess of the Aztec Triple Alliance was a defining feature of its legacy. Upon its formation, the alliance initiated a series of conquests that expanded its territory significantly. The military campaigns were characterized by strategic planning, organized troop formations, and the use of advanced weaponry, such as the atlatl and obsidian blades.

One of the first major conquests was the subjugation of the city-state of Cuauhtinchan in 1427. This victory was crucial as it established the military dominance of the alliance over central Mexico. Following this, the Triple Alliance expanded its influence into the Oaxaca region, demonstrating an ability to conquer diverse and often resistant cultures.

A key aspect of the military expansion was the use of tribute systems. Captured cities were required to pay tribute in the form of goods, resources, and even labor. This not only enriched the Aztec Empire but also integrated various cultures into its expanding domain, allowing for a diverse yet cohesive political structure.

The military campaigns were often executed with the dual purpose of conquest and diplomacy. While armed forces were deployed to suppress opposition, negotiations were also pursued with potential allies or vassal states. The Aztecs would often offer protection or trade benefits in exchange for loyalty, which further solidified their control over conquered territories.

The military success of the Triple Alliance culminated in the conquest of the expansive Tarascan state in the early 16th century, which showcased the alliance's ability to project power and influence far beyond its original boundaries. This military expansion not only secured vast resources but also facilitated the cultural assimilation of various Mesoamerican peoples into the Aztec Empire.

Economic Systems and Trade Networks

As the Aztec Empire expanded, so did its economic systems and trade networks. The Triple Alliance was instrumental in creating a complex and vast trade system that linked various regions of Mesoamerica. This network was characterized by the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices, contributing to the economic prosperity of the alliance.

The primary economic activities of the Aztecs included agriculture, tribute collection, and trade. Agriculture was the backbone of the economy, with the chinampas system of farming being particularly important. These floating gardens allowed for the cultivation of crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which were essential for sustaining the growing population of Tenochtitlan.

Trade networks extended beyond the immediate territories of the Triple Alliance, reaching as far as the Gulf Coast and the Pacific. Goods such as cacao, textiles, pottery, and luxury items flowed into Tenochtitlan, which became the economic hub of the empire. Markets were bustling with merchants who traded in a wide variety of products, facilitating not only economic transactions but also cultural exchanges.

Tribute from conquered territories played a significant role in the economic stability of the alliance. Each city-state under Aztec control was required to pay a regular tribute, which contributed to the wealth of the empire. This tribute system was meticulously organized and enforced, with local governors responsible for collecting and delivering the resources to the capital.

The economic strategies employed by the Triple Alliance also included the establishment of a standardized system of currency. The use of cacao beans and cotton cloth as mediums of exchange facilitated trade and allowed for a more organized economic structure. This innovation in trade practices laid the groundwork for future economic systems in the region and showcased the sophistication of Aztec society.

Cultural Contributions and Innovations

The cultural legacy of the Aztec Triple Alliance is profound, as it fostered a rich tapestry of artistic, religious, and scientific advancements. The confluence of cultures within the empire led to significant innovations that would influence Mesoamerican civilization for centuries.

Art and architecture flourished under the Aztec Empire, with Tenochtitlan becoming a center of artistic expression. The construction of monumental structures, such as the Templo Mayor, symbolized the religious and political power of the alliance. These structures were adorned with intricate carvings and murals that depicted religious ceremonies, historical events, and mythological stories, serving both aesthetic and didactic purposes.

Religion played a central role in Aztec culture, with a pantheon of gods that influenced various aspects of daily life. Rituals, ceremonies, and festivals were common, often incorporating music, dance, and offerings. The importance of human sacrifice in their religious practices, although controversial, was seen as a means of sustaining the gods and ensuring the continuity of life on earth.

In terms of scientific and technological advancements, the Aztecs excelled in fields such as astronomy and agriculture. They developed sophisticated calendar systems, which were crucial for agricultural cycles and religious events. The Tonalpohualli and the Xiuhpohualli calendars demonstrate the Aztecs' advanced understanding of timekeeping, celestial movements, and their implications for society.

Moreover, the Triple Alliance was integral in the preservation and dissemination of knowledge. The establishment of schools, such as the Calmecac for the nobility and the Telpochcalli for commoners, allowed for the education of young Aztecs in various subjects, including history, religion, and warfare. This emphasis on education fostered a literate society capable of sustaining the empire's cultural and intellectual pursuits.

| Cultural Contributions | Description |

|---|---|

| Art and Architecture | Creation of monumental structures and intricate art forms reflecting religious and political significance. |

| Religion | Complex pantheon of gods, rituals, and ceremonies, including human sacrifice for sustenance of the divine. |

| Scientific Knowledge | Advancements in astronomy, calendar systems, and agricultural techniques, showcasing intellectual sophistication. |

| Education | Establishment of schools promoting literacy and knowledge across different societal classes. |

The legacy of the Aztec Triple Alliance is thus marked by its military conquests, economic innovations, and cultural richness. The intricate interplay of these elements not only shaped the history of the Aztec Empire but also influenced subsequent civilizations in Mesoamerica. The impact of the Triple Alliance extended beyond its temporal existence, as it laid the groundwork for future socio-political structures, economic practices, and cultural expressions in the region.