The Aztec Concept of the Afterlife: Mictlan and the Gods of Death

The Aztec civilization, with its rich tapestry of mythology and belief systems, held a profound understanding of life and death that shaped their cultural practices and societal norms. Central to their worldview was the concept of the afterlife, which was not merely an end but a continuation of existence in a realm known as Mictlan. This underworld was intricately woven into the fabric of Aztec cosmology, reflecting their reverence for death and the journey of the soul beyond the mortal realm.

In Aztec culture, death was perceived as an essential part of life, infused with significance and ritual. The journey to Mictlan, governed by a complex set of beliefs and deities, illustrated the importance of honoring the deceased and understanding their place in the universe. As we delve into the intricacies of Mictlan and the gods of death, we uncover a fascinating perspective on how the Aztecs navigated the mysteries of mortality and the afterlife, showcasing their unique blend of spirituality and practicality.

Understanding the Aztec Beliefs About Afterlife

The Aztec civilization, one of the most advanced and influential cultures in pre-Columbian America, held complex beliefs about the afterlife that reflected their understanding of the universe, human existence, and the divine. Central to these beliefs was the idea that death was not an end but a transformation, a vital transition to another realm that was intricately tied to their cosmology, spirituality, and social practices. This section delves deeply into the Aztec understanding of the afterlife, exploring the nuances of their cosmology and the profound significance they attributed to death.

Overview of Aztec Cosmology

Aztec cosmology was a rich tapestry of myth and philosophy that explained the creation, structure, and operation of the universe. At the heart of this cosmology was the belief in multiple realms, including the heavens, the earth, and the underworld, known as Mictlan. The Aztecs conceptualized the universe as a layered structure, with the earth situated between the heavens above and the underworld below. This tripartite division was crucial in understanding their beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

The heavens were typically seen as the realm of the gods, where celestial bodies and divine entities resided. The earth, inhabited by humans, was considered a transient place, a stage for life where souls would ultimately embark on their journey to the afterlife. Below the earth lay Mictlan, the underworld, which was a complex and daunting place that souls had to navigate after death.

The Aztec worldview was also deeply intertwined with the cycles of nature, such as the agricultural calendar and the movements of celestial bodies. They believed that these cycles mirrored the cyclical nature of life and death, reinforcing the notion that death was a necessary part of existence, akin to the seasonal changes in the environment. Life was seen as a series of transformations, where every end was also a beginning, creating a continuous cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

At the core of Aztec cosmology was the belief in duality and balance. The concepts of life and death, light and darkness, and creation and destruction were viewed as complementary forces. This duality was not only reflected in their myths and rituals but also in their understanding of the afterlife. The Aztecs believed that the journey of the soul was influenced by the manner of one's death, the actions taken during life, and the offerings made to the gods.

Significance of Death in Aztec Culture

Death held a significant place in Aztec culture, viewed not as a tragic endpoint but as a vital part of the human experience. The Aztecs celebrated death with rituals and festivals, integrating it into their daily lives rather than shying away from it. This acceptance stemmed from their belief that death was a gateway to Mictlan and the afterlife, where souls would continue to exist in a different form.

One of the most important festivals related to death was the *Mictecacihuatl*, or the Day of the Dead, which honored deceased ancestors and celebrated the continuity of life through remembrance. During this festival, families would create altars, known as *ofrendas*, adorned with offerings such as food, flowers, and personal items to welcome the spirits of the deceased back to the earthly realm. This practice underscored the belief that the dead remained present in the lives of the living, fostering a connection across realms.

Additionally, the Aztecs believed that the manner of one's death played a critical role in determining the soul's destiny in the afterlife. Those who died in battle, during childbirth, or through sacrifice were thought to ascend to a higher realm, often becoming part of the sun's journey or joining the gods in the heavens. In contrast, those who died of natural causes or in less honorable ways faced a more arduous journey through Mictlan, where they would encounter various challenges before finding peace.

The importance of death in Aztec culture also manifested in their funerary practices. The Aztecs conducted elaborate burial rituals that included offerings to the dead, the construction of tombs, and ceremonies conducted by priests. These practices were designed to honor the deceased and ensure their safe passage to the afterlife. The accompanying beliefs emphasized the need for proper rites to avoid the restless spirits of the dead haunting the living.

In summary, the Aztec understanding of the afterlife was a complex interplay of cosmology, ritual practices, and cultural beliefs. It represented a deep reverence for the cycle of life and death, where each stage was interconnected and significant. The afterlife was not merely a destination but an ongoing journey that shaped the lives of the living through memory, ritual, and the intimate connection between the two realms.

Mictlan: The Underworld of the Aztecs

The concept of Mictlan, the Aztec underworld, is a profound and intricate part of Aztec cosmology and spirituality. It reflects the civilization's understanding of life, death, and what lies beyond. Mictlan is not merely a destination for the deceased but a complex realm where souls embark on a challenging journey after death. This section delves into the structure and geography of Mictlan, the arduous journey of souls to this realm, and the key deities associated with it.

Structure and Geography of Mictlan

Mictlan is often depicted as a dark, expansive land located to the north of the earthly realm, characterized by its various layers and challenges that souls must face. The Aztecs believed that Mictlan was divided into nine distinct levels, each presenting unique obstacles and trials that the deceased had to overcome to reach their final resting place.

- First Level: Chignahuapan - The souls arrive in a realm filled with the echoes of their past lives. They are greeted by the spirit of the deceased who guide them through the initial stages of their journey.

- Second Level: Tlalocan - This area is characterized by a desolate landscape where the souls encounter the spirits of those who died by drowning or water-related incidents.

- Third Level: The Place of the Obsidian Knife - Here, the souls must pass through a place filled with sharp stones and blades, symbolizing the pain associated with death.

- Fourth Level: The Land of the Dead - In this level, souls encounter various spirits, including those who died of natural causes, and must seek forgiveness for their earthly transgressions.

- Fifth Level: The Place of Eternal Darkness - This area represents the fear of the unknown, where souls must confront their fears and regrets.

- Sixth Level: The River of Blood - Souls are challenged to cross a river that symbolizes the sacrifices made in life, where they must reflect on their actions.

- Seventh Level: The Land of the Forgotten - In this desolate area, souls encounter those who have no one to remember them, representing the importance of legacy.

- Eighth Level: The Place of the Lost - Here, souls must navigate through memories of their past lives, confronting unresolved issues and relationships.

- Ninth Level: The Final Resting Place - This is the ultimate destination, where souls find peace after completing their journey through Mictlan.

The geography of Mictlan is not only a physical representation of the afterlife but also a metaphor for the challenges and experiences that each soul must face. This complex structure highlights the Aztec belief that death is not an end but a transformation, a necessary journey towards spiritual enlightenment and unity with the cosmos.

The Journey of Souls to Mictlan

The journey to Mictlan begins at the moment of death, where the soul is separated from the body. According to Aztec beliefs, the soul, known as tonalli, must navigate through various challenges to reach Mictlan. The deceased must be guided by a spirit, often a family member or a deity, who aids them in overcoming obstacles along the way.

One of the most critical aspects of this journey is the crossing of the river Ahuizotl, a dangerous body of water guarded by the fearsome creature of the same name. Souls must find a way to cross this river, often requiring offerings or sacrifices to appease the creature. This emphasizes the importance of rituals and offerings in Aztec culture, as they believed that proper burial rites and offerings could ease the passage of the soul into the afterlife.

Throughout the journey, souls encounter various tests that reflect their actions during their lifetime. Those who lived honorable lives are believed to have a smoother passage, while those with unresolved issues or negative deeds face more significant challenges. This journey symbolizes the Aztec belief in accountability and the importance of living a virtuous life.

It's important to note that the journey to Mictlan is not a straightforward path. Souls may wander in the underworld for years, facing trials and tribulations until they finally reach the final resting place. This concept highlights the Aztec understanding of time and existence; the journey itself is a vital part of the soul's transformation.

Key Deities Associated with Mictlan

Mictlan is closely associated with several deities that play crucial roles in the afterlife journey. These gods and goddesses embody various aspects of death, the underworld, and the spiritual journey of souls. Among them, Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl stand out as the primary deities.

| Deity | Role |

|---|---|

| Mictlantecuhtli | The Lord of the Underworld, governing Mictlan and overseeing the souls' journey. |

| Mictecacihuatl | The Lady of the Dead, who watches over the souls and ensures proper rituals are followed for their passage. |

| Xolotl | The twin brother of Quetzalcoatl, representing the evening star and guiding souls to Mictlan. |

| Tlaloc | The rain god, associated with the natural cycles of life and death, influencing the journey to Mictlan. |

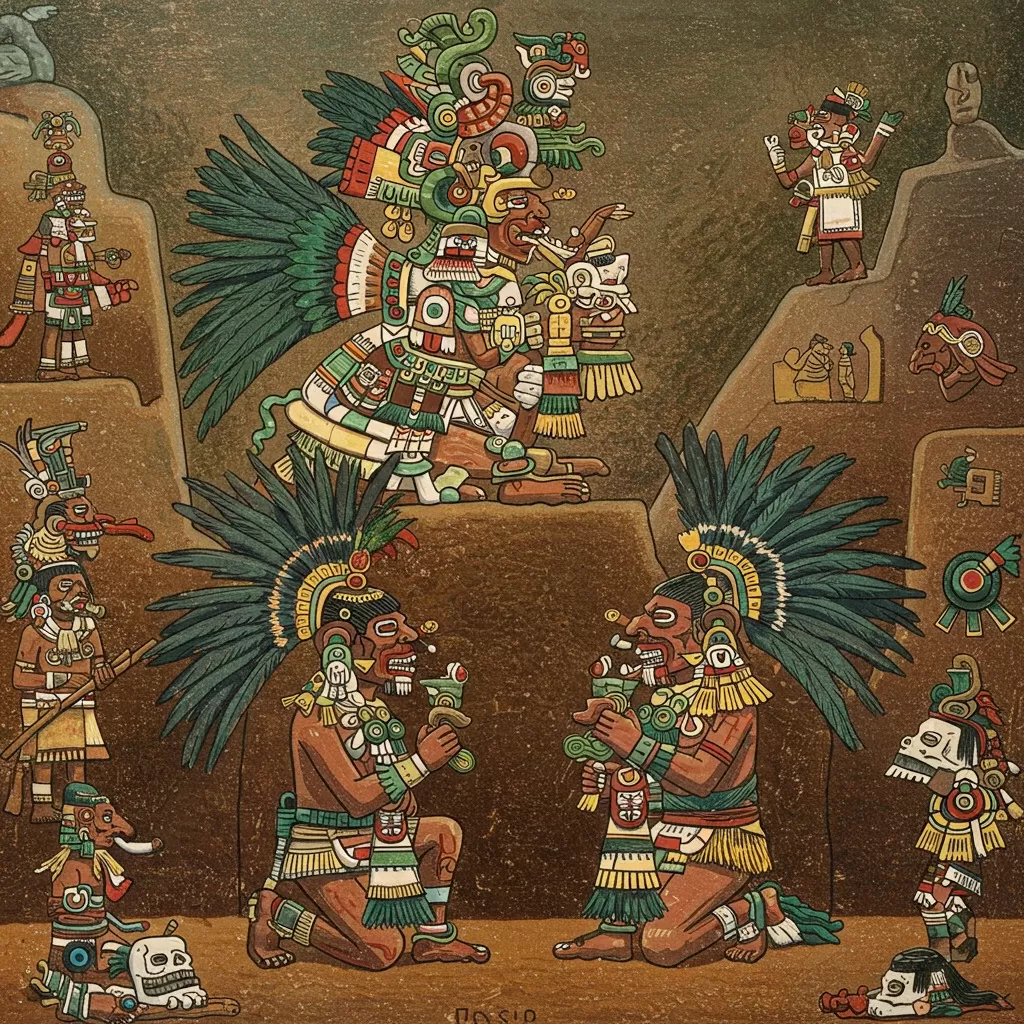

Mictlantecuhtli, often depicted as a skeletal figure adorned with symbols of death, plays a central role in Aztec mythology as the ruler of Mictlan. He embodies death's inevitability and the natural cycle of life. His counterpart, Mictecacihuatl, is equally significant. She is often portrayed as a skeletal woman who presides over the dead. Together, they symbolize the duality of life and death, emphasizing the interconnectedness of these states of existence.

Xolotl, the twin of Quetzalcoatl, is another essential deity linked to Mictlan. He is known as the guide for souls, helping them navigate the treacherous paths of the underworld. His role is crucial in ensuring that the souls reach Mictlan safely, reflecting the belief that divine guidance is necessary for a successful afterlife journey.

In addition to these primary deities, other gods and spirits are associated with various aspects of death and the afterlife, including Tlaloc, the rain god, who influences the natural cycles that govern life and death. These deities represent the multifaceted nature of Aztec beliefs regarding the afterlife, illustrating that death is not a singular event but a complex journey involving divine intervention, accountability, and transformation.

The reverence for these deities is evident in Aztec rituals and ceremonies, which often included offerings, sacrifices, and prayers intended to honor and appease them. These practices were crucial for ensuring a smooth transition for the deceased and for maintaining the balance between the living and the dead.

In summary, Mictlan represents not only the underworld of the Aztecs but also an intricate system of beliefs regarding death, the afterlife, and the spiritual journey of souls. Its structure, the arduous journey souls must undertake, and the key deities associated with it reflect the profound understanding of life and death in Aztec culture. Mictlan is a testament to the civilization's rich spiritual heritage and its enduring influence on the perception of the afterlife.

The Gods of Death in Aztec Mythology

The Aztec civilization had a rich and complex mythology surrounding death and the afterlife, which played a crucial role in their culture and religious beliefs. Central to these beliefs were the gods of death, who governed the process of dying, the afterlife, and the souls of the departed. Understanding these deities provides insight into how the Aztecs viewed mortality and the significance of death within their society. This section explores the primary gods associated with death in Aztec mythology, focusing on Mictlantecuhtli, Mictecacihuatl, and other notable deities that influenced the perceptions and rituals surrounding death.

Mictlantecuhtli: The Lord of the Underworld

Mictlantecuhtli, often referred to as the "Lord of the Underworld," is one of the most prominent figures in Aztec mythology. He was considered the ruler of Mictlan, the Aztec underworld, where souls traveled after death. His name translates to "Lord of Mictlan," and he was depicted as a skeletal figure adorned with a headdress of owls and a necklace made of human bones. His fearsome appearance symbolized the inevitable fate that awaited all mortals, making him both a revered and feared deity.

Mictlantecuhtli was believed to preside over the four-year cycle of life and death, which was represented in Aztec calendars. His role extended beyond merely receiving souls; he was also responsible for the conditions of their afterlife. Souls that reached Mictlan faced trials and tribulations during their journey, reflecting the Aztecs' belief in the importance of living a virtuous life. In Aztec culture, a proper burial and rituals were essential to ensure that one’s soul could navigate these challenges and reach Mictlan peacefully.

The Aztecs honored Mictlantecuhtli through various rituals and offerings, particularly during the festival of the dead known as Miccailhuitl. This celebration involved honoring deceased ancestors and included sacrifices, food offerings, and the creation of altars to appease the god. The rituals were designed to ensure that Mictlantecuhtli would accept the souls of the departed and provide them with a safe passage to the afterlife.

Mictecacihuatl: The Lady of the Dead

Mictecacihuatl, known as the "Lady of the Dead," was the female counterpart of Mictlantecuhtli and played a significant role in Aztec death mythology. She was depicted as a skeletal woman, often shown with her mouth open, symbolizing her role as a guardian of the dead. Mictecacihuatl was responsible for overseeing the bones of the deceased and was believed to preside over the festivals honoring the dead.

As the Lady of the Dead, Mictecacihuatl had the crucial responsibility of ensuring that the souls of the departed were treated with respect and given the necessary offerings. She was particularly honored during the Day of the Dead celebrations, where families would create altars adorned with photographs, food, and personal items of their deceased loved ones. This custom reflects the belief that the spirits of the dead would return to the living world to receive these offerings.

Mictecacihuatl’s relationship with Mictlantecuhtli emphasized the duality of life and death in Aztec thought. While Mictlantecuhtli represented the fearsome aspect of death, Mictecacihuatl embodied the nurturing side, emphasizing the importance of honoring and remembering those who had passed away. Together, they represented the balance between life and death, a concept that was central to the Aztec worldview.

Other Notable Death Deities and Their Roles

In addition to Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl, the Aztec pantheon included several other deities associated with death, each with unique roles and significance in the afterlife narrative. These gods contributed to the rich tapestry of beliefs surrounding mortality and the afterlife in Aztec culture.

- Xolotl: Xolotl was the twin brother of Quetzalcoatl and a significant figure in Aztec mythology. He was often depicted as a dog-headed deity associated with death and the underworld. Xolotl was believed to guide souls to Mictlan, serving as a protector during their journey. His association with the evening star and lightning also linked him to the cycles of life and death, making him a crucial figure in the cosmic balance.

- Tlaloc: Although primarily known as the god of rain and fertility, Tlaloc had connections to death through his role in the life cycle of crops. The Aztecs believed that drought and famine were manifestations of his wrath, leading to death and suffering. In this way, Tlaloc’s influence extended beyond the living, affecting the deceased and their journey in the afterlife.

- Tezcatlipoca: Tezcatlipoca, the god of the night sky and sorcery, also played a role in death and the afterlife. He represented the unpredictability of life and was often associated with conflict and struggle. His influence over fate and destiny meant that he had the power to determine the outcomes of souls in the afterlife, further complicating the Aztec understanding of mortality.

The roles of these deities illustrate the complexity of Aztec beliefs regarding death. Instead of viewing death as a singular event, the Aztecs perceived it as part of a broader cosmic cycle influenced by various gods. Each deity contributed to the understanding of life, death, and the afterlife, providing comfort and guidance to the living as they navigated the inevitability of mortality.

Rituals and Offerings to the Gods of Death

The Aztecs engaged in numerous rituals and ceremonies to honor their gods of death, reflecting their deep reverence and fear of these powerful deities. These practices were integral to their religious and cultural identity and served to connect the living with their ancestors and the divine.

One of the most significant rituals was the festival of Miccailhuitl, which took place in the month of Miccailhuitl in the Aztec calendar. This festival lasted for several days and involved elaborate ceremonies, including music, dance, and offerings to Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl. Families would visit the graves of their ancestors, bringing food, flowers, and other offerings to ensure that the souls of the departed were honored. The festivities included the creation of altars, known as ofrendas, which were decorated with photographs and mementos of the deceased, symbolizing the enduring bond between the living and the dead.

Additionally, the Aztecs performed rituals throughout the year to appease the gods of death. These included blood sacrifices, which were believed to nourish the deities and ensure their favor. The Aztecs understood that the gods of death had the power to influence the living, and thus, maintaining their goodwill was crucial for the survival and prosperity of the community.

Artistic representations of Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl also played a role in rituals. Sculptures, codices, and pottery often depicted these deities, serving as focal points for worship and devotion. These artistic expressions were not merely decorative; they were imbued with spiritual significance, connecting the physical realm with the divine.

The Legacy of Aztec Death Deities

The influence of Aztec gods of death extended beyond their immediate cultural context, shaping contemporary understandings of death and the afterlife in Mexico. The legacy of Mictlantecuhtli, Mictecacihuatl, and their counterparts continues to resonate in modern Mexican culture, particularly during the Day of the Dead celebrations, known as Día de Muertos. This holiday honors deceased loved ones and reflects a blend of indigenous and Catholic traditions, showcasing the enduring impact of Aztec beliefs on contemporary practices.

The imagery associated with these deities, such as skeletons and skulls, has become emblematic of Mexican culture, particularly during Día de Muertos. The celebration serves as a reminder of the cyclical nature of life and death, echoing the Aztec understanding of mortality as a transition rather than an end. The rituals performed today, including the creation of altars and the sharing of food, mirror the ancient practices dedicated to honoring the gods of death and the spirits of the departed.

The enduring fascination with Aztec mythology, particularly the gods of death, has also influenced literature, art, and popular culture. From novels exploring the mythological narratives to visual art that incorporates elements of Aztec iconography, the legacy of these deities continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the world.

In summary, the gods of death in Aztec mythology—Mictlantecuhtli, Mictecacihuatl, and their counterparts—played a crucial role in shaping the Aztec understanding of life, death, and the afterlife. Their complex relationships and the rituals associated with them reflect the rich cultural heritage of the Aztecs, emphasizing the importance of honoring those who have passed and acknowledging the inevitability of death. As Mexico continues to celebrate its connections to its indigenous past, the legacy of these death deities remains a vital part of its cultural identity.