The Ancient Maya Economy: Trade and Agriculture

The Ancient Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in architecture, astronomy, and writing, also had a complex and dynamic economy that played a crucial role in its development and sustainability. At the heart of this economy were two fundamental pillars: trade and agriculture. Understanding how these elements interacted provides insight into the daily lives of the Maya people, their social structures, and their cultural practices. By examining the intricacies of trade routes and agricultural techniques, we can appreciate the sophistication of Maya society and its adaptability to the challenges of their environment.

Trade was not merely a means of exchanging goods; it fostered relationships among different city-states and facilitated the flow of ideas and cultural practices. The Maya engaged in extensive trade networks that connected them to distant regions, allowing them to acquire valuable resources and commodities. Meanwhile, agriculture, the backbone of their economy, ensured food security and supported population growth. This article delves into the multifaceted aspects of the Maya economy, exploring how trade and agriculture intertwined to shape one of history's most fascinating civilizations.

Understanding the Ancient Maya Economy

The ancient Maya civilization, which thrived in Mesoamerica from approximately 2000 BCE to the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, boasted a complex and sophisticated economy that was intricately linked to its social structure, culture, and environment. Understanding the ancient Maya economy requires delving into the historical context of the Maya civilization and examining its economic structure and organization.

Historical Context of the Maya Civilization

The Maya civilization reached its zenith during the Classic Period, from around 250 to 900 CE, when city-states such as Tikal, Calakmul, and Palenque flourished. The development of a centralized economy was vital for sustaining the large populations of these city-states. Agricultural surplus, particularly in maize, facilitated the growth of urban centers, while trade networks extended far beyond regional boundaries, incorporating diverse resources from both highland and lowland areas.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Maya practiced various forms of agriculture, including slash-and-burn techniques, terracing, and raised-field farming. The environment played a crucial role in shaping agricultural practices, which varied across the different geographic regions inhabited by the Maya. The lowland areas, characterized by tropical rainforests, were rich in biodiversity and provided a variety of crops, while the highlands offered different agricultural advantages.

Moreover, the social and political organization of the Maya significantly influenced their economy. The civilization was structured around city-states, each led by a ruler who wielded considerable power and authority. These rulers often engaged in warfare, which not only served to expand territory but also to control trade routes and resources. The interplay between warfare, trade, and agriculture created a dynamic economic landscape in which the Maya thrived.

Economic Structure and Organization

The economic structure of the ancient Maya was multifaceted, involving agriculture, trade, and crafts. The foundation of their economy was agriculture, which provided the necessary sustenance for the population and surplus for trade.

Agriculture was organized around the cultivation of staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, often referred to as the "Mesoamerican triad." This combination of crops not only ensured a balanced diet but also contributed to soil fertility through crop rotation and intercropping techniques. The Maya also cultivated cacao, a highly valued commodity that played a significant role in trade and was used to make a ceremonial beverage.

In addition to agriculture, the Maya engaged in extensive trade, facilitated by a network of established trade routes that connected different regions and city-states. Trade was not just a means of economic exchange; it also served to strengthen political alliances and cultural connections. The Maya traded a variety of goods, including textiles, ceramics, obsidian, and jade, each of which held social and ritual significance.

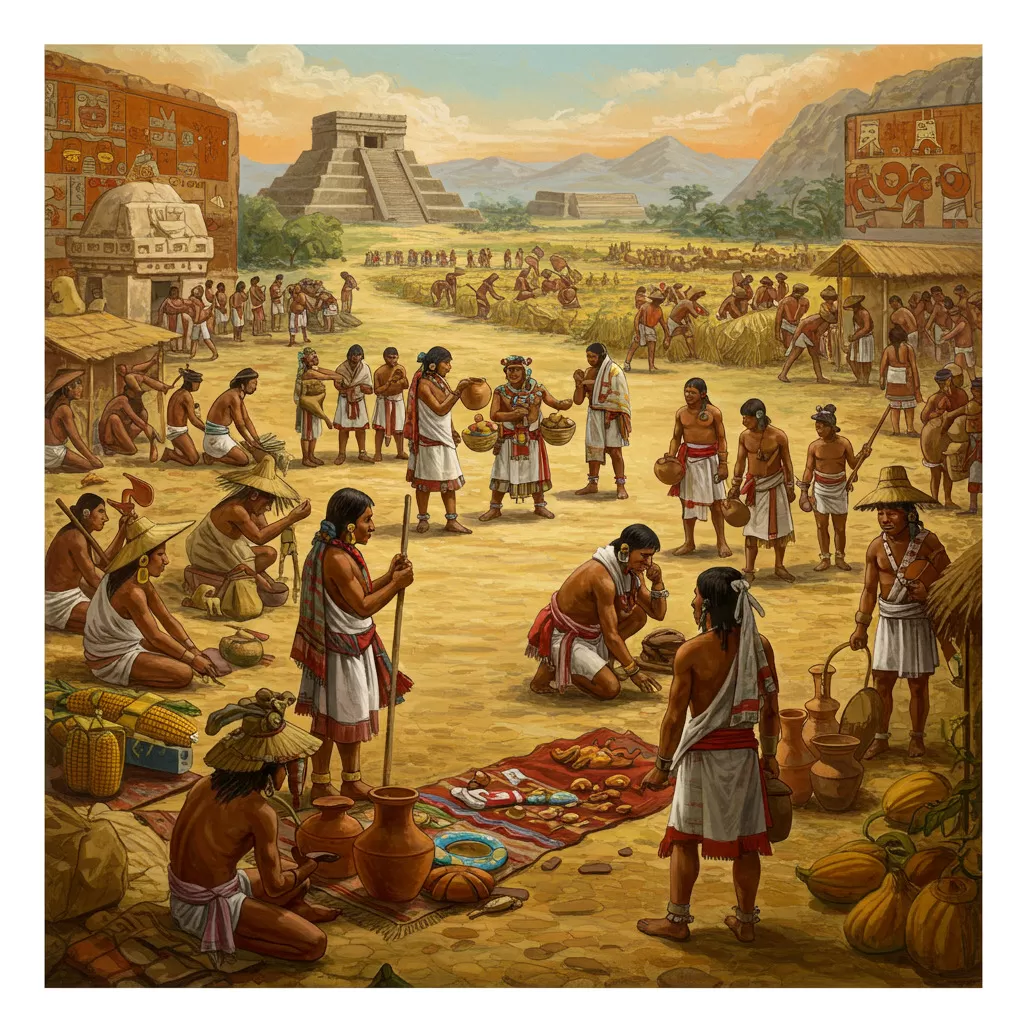

The role of merchants, known as "pochteca," was crucial in the economic framework of the Maya. These merchants were responsible for long-distance trade and often acted as diplomats, conveying messages between city-states. They were organized into guilds that ensured the regulation of trade practices and maintained a level of trust among merchants. Marketplaces, or "tianguis," served as vibrant centers of commerce and social interaction, where goods were exchanged, and cultural practices were reinforced.

To understand the economic organization further, it is essential to examine the roles of government and religion in regulating the economy. Maya rulers often dictated trade practices, imposing taxes and tribute systems that ensured a steady flow of resources to support their courts and public works. Religious beliefs also influenced economic activities, as many agricultural practices were tied to rituals and ceremonies that honored deities associated with fertility and harvest.

In summary, the ancient Maya economy was a complex system that combined agriculture, trade, and social organization. The interplay of these elements not only sustained the civilization through centuries but also shaped its cultural identity and legacy.

Understanding the Maya economy requires an appreciation of the historical context and the intricate social, political, and environmental factors that shaped their economic practices. As we delve deeper into the trade practices and agricultural practices of the Maya civilization in subsequent sections, we will uncover the richness and depth of this remarkable society.

Trade Practices in the Maya Civilization

The ancient Maya civilization, flourishing between 250 and 900 CE, is renowned for its remarkable achievements in various fields, including astronomy, architecture, and agriculture. However, one of the most significant aspects of Maya society was its complex economy, heavily reliant on trade practices that facilitated the exchange of goods and cultural ideas across vast regions. This section delves into the intricacies of the trade networks and practices of the Maya civilization, exploring key trade routes, the variety of goods traded, and the essential roles played by merchants and marketplaces.

Key Trade Routes and Networks

The Maya civilization encompassed a vast geographic area, including present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. This extensive territory was interspersed with diverse environments, from coastal regions to highland mountains, each contributing to the variety of goods available for trade. The Maya established intricate trade routes that connected various city-states, allowing for the efficient exchange of resources and commodities.

Trade routes were primarily overland and maritime, with major pathways linking important cities like Tikal, Calakmul, Palenque, and Copán. The use of rivers, such as the Usumacinta and the Grijalva, facilitated the transportation of goods, especially in regions where roads were less developed. The Maya also utilized canoes to traverse waterways, enhancing their trade capabilities.

In addition to local trade, the Maya engaged in long-distance trade with neighboring cultures, including the Teotihuacan in central Mexico and the Olmec. The exchange between these cultures led to the assimilation of various artistic styles, religious beliefs, and agricultural techniques, enriching the Maya civilization's cultural fabric.

Archaeological evidence suggests that trade was not only a means of economic sustenance but also a way to forge alliances and establish diplomatic relations between different city-states. The exchange of luxury goods, such as jade and obsidian, served as symbols of power and prestige, reinforcing social hierarchies within the Maya society.

Goods Traded: From Cacao to Textiles

The Maya traded a wide array of goods, reflecting their diverse economy and cultural preferences. One of the most important and sought-after commodities was cacao, which was highly valued not only as a food source but also as a form of currency. Cacao beans were used to create a frothy, bitter beverage often consumed by the elite during rituals and social gatherings. The significance of cacao in Maya society is evident in the many references to it in their codices and art, showcasing its cultural and economic importance.

In addition to cacao, the Maya traded various agricultural products such as maize, beans, squash, and chili peppers, staples that formed the backbone of their diet. The cultivation of these crops was essential for sustaining the population and supporting trade networks. The surplus production of these goods allowed for specialization in other sectors, further enhancing the economy.

Textiles were another crucial commodity in the Maya trade system. The intricate weaving of cotton and other fibers produced colorful garments that showcased the skills of Maya artisans. These textiles were often adorned with elaborate patterns and symbols, signifying social status and identity. The demand for textiles extended beyond local markets, as they were traded with neighboring cultures, further integrating the Maya into broader trade networks.

Other goods traded included pottery, tools, and luxury items such as jade, obsidian, and feathers. The exchange of these items not only satisfied material needs but also fostered cultural exchanges, as artisans from different regions shared techniques and styles, enriching the artistic traditions of the Maya.

Role of Merchants and Marketplaces

Merchants played a vital role in the Maya economy, acting as intermediaries between producers and consumers. They were responsible for the transportation and distribution of goods across trade routes, often traveling long distances to acquire sought-after products. Merchants were not only traders but also cultural ambassadors, facilitating the exchange of ideas and customs between different regions.

Marketplace activities were integral to Maya society, with open-air markets serving as hubs of economic and social interaction. These markets were typically held in central plazas of city-states, attracting people from surrounding areas. They provided a platform for the exchange of goods, information, and cultural practices, allowing for the development of a vibrant marketplace culture.

The structure of these marketplaces varied, with goods organized by type and vendors showcasing their wares. Archaeological findings suggest that barter was the primary method of exchange, although some communities may have utilized a form of currency, particularly cacao beans, for transactions. The bustling atmosphere of the marketplaces reflected the dynamic nature of the Maya economy, where social relationships were built and maintained through trade.

Furthermore, merchants often formed guilds or associations that offered mutual support and protection, enhancing their ability to navigate the complexities of trade. These groups helped regulate pricing, maintain quality standards, and ensure fair exchanges, contributing to the overall stability of the economy.

In conclusion, trade practices in the Maya civilization were multifaceted and deeply embedded in their social, cultural, and economic fabric. The establishment of key trade routes and networks, the variety of goods exchanged, and the roles played by merchants and marketplaces all contributed to a vibrant and dynamic economy that not only sustained the Maya people but also facilitated cultural exchanges that would shape their civilization for centuries.

Key Takeaways:- Trade was essential to the economic structure of the Maya civilization, facilitating the exchange of goods and cultural ideas.

- Cacao, textiles, and agricultural products were among the most significant commodities traded.

- Merchants acted as intermediaries and cultural ambassadors, playing a crucial role in the trade networks.

- Marketplaces served as vital centers for economic and social interaction, fostering community ties.

Agricultural Practices and Their Impact

The ancient Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in various fields, had a profound relationship with agriculture. This relationship not only formed the backbone of their economy but also influenced their social structure, cultural practices, and spiritual beliefs. The agricultural techniques employed by the Maya were sophisticated and adaptive, enabling them to thrive in the diverse environments of Mesoamerica. This section delves into the intricacies of Maya agricultural practices, the central role of staple crops like maize, and the broader implications of agriculture on Maya society and culture.

Farming Techniques and Crop Diversity

The Maya developed several innovative farming techniques to maximize their agricultural output, particularly in the varied terrains of the Yucatán Peninsula and surrounding areas. Key among these techniques was the practice of slash-and-burn agriculture, known as milpa. This method involved clearing a section of forest by cutting down vegetation and burning it. The ashes provided nutrient-rich soil that was ideal for planting. However, the milpa system required rotation and fallow periods to maintain soil fertility, as continuous planting depleted the land.

In addition to slash-and-burn, the Maya also utilized terracing, particularly in hilly regions. Terracing allowed them to create flat fields on steep slopes, reducing soil erosion and enhancing water retention. These terraces were often equipped with sophisticated drainage systems to prevent waterlogging during heavy rains. This ingenuity in farming practices demonstrates the Maya’s deep understanding of their environment and their ability to manipulate it to their advantage.

Crop diversity was another hallmark of Maya agriculture. While maize was the cornerstone of their diet, the Maya cultivated a variety of other crops, including beans, squash, chili peppers, and cacao. The combination of these crops not only ensured a balanced diet but also supported the three sisters agricultural technique, where maize, beans, and squash were planted together. This method allowed the plants to support each other; maize provided a structure for the beans to climb, beans enriched the soil with nitrogen, and squash spread across the ground, suppressing weeds and retaining moisture.

Furthermore, the Maya engaged in the cultivation of fruit trees such as avocados and guavas, and they even farmed root vegetables and herbs. This agricultural diversity was crucial for sustaining the population and allowed for a resilient economy that could withstand fluctuations in climate and market demands. The integration of various farming techniques and crop types reflects the Maya's adaptability and their rich agricultural heritage.

Importance of Maize and Other Staple Crops

Maize (Zea mays) holds a sacred place in Maya culture, often referred to as the mother grain. Its cultivation and consumption were central to Maya life, providing not only sustenance but also a symbol of identity and community. The importance of maize transcended mere nutrition; it was deeply intertwined with mythology, religion, and social structure. According to the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Maya, humans were created from maize dough by the gods. This narrative illustrates how maize was seen as the essence of life itself.

The role of maize in Maya society extended to its use in rituals and ceremonies. It was a primary ingredient in traditional foods such as tortillas, tamales, and beverages like atole and pozole. Festivals celebrating the maize harvest were common, highlighting the significance of this crop in agricultural cycles. The Maya also developed various maize varieties suited to different climatic conditions, ensuring a stable supply throughout the year. This agricultural prowess allowed them to support large urban populations, ranging from city-states like Tikal to Copán.

In addition to maize, other staple crops played vital roles in the Maya diet and economy. Beans served as an essential protein source, complementing the carbohydrate-rich maize. Squash, with its high water content, was crucial for hydration, especially in the dry season. Additionally, the Maya cultivated cacao, which was highly valued not only as a food item but also as a form of currency and a beverage for the elite. Cacao beans were so prized that they were often used in trade and as offerings in religious ceremonies, underlining their economic and spiritual significance.

The Maya's agricultural practices and crop choices were not merely about sustenance; they were a reflection of their worldview, where agriculture was seen as a divine gift and a communal responsibility. This connection to the land and its bounty fostered a deep respect for nature, influencing their cultural practices and social interactions.

Agriculture's Influence on Maya Society and Culture

The agricultural practices of the Maya had profound implications for their social structure and cultural development. As agriculture became more productive, it supported larger populations, leading to the growth of city-states and complex societies. This demographic increase facilitated the development of social hierarchies, with a clear distinction between the elite and the commoners. The ruling class, often composed of nobles and priests, exerted control over agricultural production, land ownership, and labor. This led to the establishment of a tribute system where commoners worked the land and paid taxes in the form of crops to support the ruling elite and religious institutions.

The surplus generated by agricultural practices allowed the Maya to invest in monumental architecture, art, and science. The construction of temples, palaces, and observatories required a significant labor force, which was only possible due to the agricultural surplus. This investment in infrastructure and cultural production is evident in the remains of sophisticated cities adorned with intricate carvings and murals that depict agricultural scenes and deities associated with fertility and abundance.

Moreover, the Maya’s agricultural practices influenced their spiritual beliefs and cosmology. Many deities were associated with agriculture and fertility, with rituals and offerings performed to ensure bountiful harvests. The agricultural calendar, which dictated the timing of planting and harvesting, was intertwined with religious festivals, creating a cultural rhythm that governed daily life. This cyclical understanding of time and agriculture reinforced the connection between the Maya people and their environment, emphasizing the need for harmony with nature.

The importance of agriculture also extended to social cohesion. Community farming practices fostered collaboration and mutual support among households, as families worked together to prepare the land, plant, and harvest. This collective effort contributed to the development of strong social bonds and a sense of shared responsibility for the community's well-being.

In conclusion, the agricultural practices of the ancient Maya were not merely utilitarian; they were the foundation of their civilization. The intricate farming techniques, the revered status of maize and other staple crops, and the societal structures that emerged from agricultural surplus all highlight the deep interconnections between agriculture, culture, and identity. The legacy of Maya agriculture continues to be felt today, as contemporary communities in the region still engage in traditional farming methods and maintain cultural ties to their ancient heritage.