Olmec Social Structure: Classes, Labor, and Elites

The Olmec civilization, often regarded as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, boasts a rich and complex social structure that laid the groundwork for future societies in the region. Emerging around 1200 BCE in what is now southern Mexico, the Olmecs were not only skilled artisans and traders but also pioneers in establishing a societal hierarchy that would influence generations to come. Understanding their social organization provides crucial insights into the dynamics of power, class, and labor that shaped their daily lives and cultural achievements.

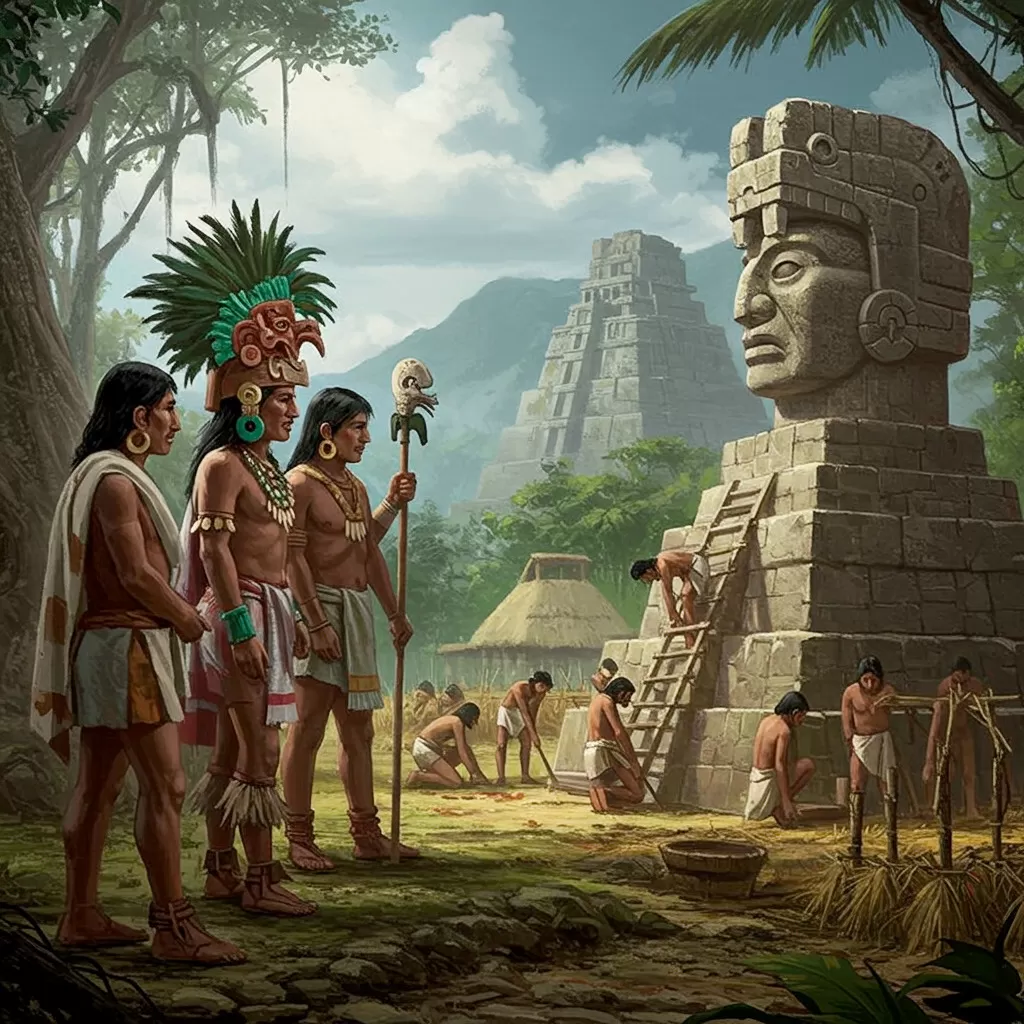

At the heart of Olmec society was a stratified class system, consisting of elites, middle-class artisans, and the lower-class farmers and laborers. This structure was essential for maintaining order and facilitating economic activities, while also reinforcing the authority of rulers and priests who played pivotal roles in both governance and religious practices. By exploring the various classes within Olmec civilization, we can better appreciate how their social framework contributed to their advancements in agriculture, trade, and craftsmanship, ultimately influencing the broader tapestry of Mesoamerican history.

Understanding Olmec Society

The Olmec civilization, flourishing between approximately 1200 BCE and 400 BCE in present-day southern Mexico, is often regarded as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica. This term acknowledges the profound influence and foundational role the Olmecs played in shaping subsequent Mesoamerican societies, including the Maya and Aztec civilizations. Understanding the societal structure of the Olmecs is crucial for comprehending their cultural achievements, social dynamics, and historical legacy.

Historical Context of the Olmecs

The rise of the Olmec civilization occurred during a transformative period in Mesoamerican history. Prior to the Olmecs, the region was characterized by small, scattered communities primarily engaged in subsistence agriculture. The Olmecs, however, were pioneers in establishing complex societies characterized by urban centers, monumental architecture, and an intricate social hierarchy.

One of the most significant archaeological sites linked to the Olmecs is San Lorenzo, which served as a cultural and political hub around 1200 BCE. Here, the Olmecs constructed massive stone heads, altars, and platforms, demonstrating advanced engineering and artistic skills. The subsequent rise of La Venta, around 900 BCE, further exemplified the Olmec's architectural prowess and their ability to organize labor for large-scale projects.

During this period, the Olmecs developed a rich cultural identity that included religious practices, artistic traditions, and early forms of writing and mathematics. Their influence can be traced through various elements such as religious iconography, the ball game, and calendrical systems that permeated later Mesoamerican civilizations.

Geographic and Cultural Influences

The Olmec heartland is located in the tropical lowlands of the Gulf Coast, encompassing modern-day states such as Veracruz and Tabasco. This geographic setting provided both challenges and opportunities for the Olmec people. The abundant rivers, fertile lands, and access to the Gulf of Mexico facilitated agriculture, trade, and cultural exchange.

The Olmecs capitalized on their environment by developing agricultural techniques suited to the region's tropical climate. They cultivated staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which formed the basis of their diet and economy. Additionally, the Olmecs engaged in extensive trade networks, exchanging goods such as obsidian, jade, and ceramics with neighboring cultures, thereby enriching their society and enhancing their cultural synthesis.

Culturally, the Olmecs were influenced by neighboring groups, yet they also established distinct traditions that set them apart. Their religious beliefs, centered around a pantheon of deities often depicted as jaguars and serpents, were integral to their identity. The Olmec artistic style, characterized by intricate carvings and colossal stone heads, reflects a sophisticated understanding of form and symbolism, paving the way for future Mesoamerican art.

The Olmec civilization's legacy is evident in the cultural and religious practices that continued to thrive in Mesoamerica long after their decline. Their innovations in governance, artistic expression, and trade established a framework for the development of subsequent civilizations, making them a cornerstone of Mesoamerican history.

Class Structure in Olmec Civilization

The Olmec civilization, often referred to as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, emerged around 1200 BCE in what is now southern Mexico. The social structure of the Olmecs was complex and multifaceted, reflecting a society that engaged in various economic activities and had distinct social classes. This section delves into the class structure of Olmec civilization, focusing on the elite, middle, and lower classes, and examining their roles, contributions, and interactions within this ancient society.

The Elite Class: Rulers and Priests

The elite class in Olmec society was integral to the governance and religious life of the civilization. This class consisted primarily of rulers and priests, who held significant power and influence. They were responsible for making crucial decisions regarding the administration of the city-states and the spiritual well-being of the populace.

Rulers were often seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people. They were believed to possess divine authority, which legitimized their rule and allowed them to command respect and obedience from their subjects. The Olmec rulers were typically associated with monumental architecture, such as the colossal heads and other large stone sculptures found at sites like San Lorenzo and La Venta. These structures were not only artistic expressions but also served to reinforce the power and prestige of the elite class.

Priests played a dual role in Olmec society. They were responsible for conducting religious ceremonies, which were essential for maintaining the favor of the gods. These ceremonies often involved complex rituals, including offerings, bloodletting, and possibly even human sacrifice. The priests were knowledgeable in the ways of the cosmos and agriculture, and they provided guidance on when to plant and harvest crops, which was critical for the agrarian society.

The elite class also controlled the distribution of resources, including agricultural produce and luxury goods. This control allowed them to maintain their status and ensure the loyalty of the lower classes. The wealth and power of the elite were often reflected in their burial practices, which included elaborate tombs filled with valuable artifacts, indicating a belief in an afterlife where status would continue beyond death.

The Middle Class: Artisans and Merchants

The middle class of the Olmec civilization was composed mainly of artisans and merchants. This class played a vital role in the economic framework of Olmec society, contributing to both local and regional economies through their crafts and trade networks.

Artisans were skilled workers who produced a variety of goods, including pottery, textiles, and stone carvings. Their craftsmanship was highly valued, and it is believed that they often worked in workshops that were possibly organized by the elite. The quality of Olmec art, particularly the intricate jade carvings and figurines, suggests a high level of skill and creativity. These artisans not only served the local community but also created goods that were traded with neighboring cultures, which further enhanced their social standing.

Merchants, on the other hand, were essential for the exchange of goods across vast distances. The Olmecs established trade routes that connected them with other Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya and the Zapotecs. They traded valuable resources such as jade, obsidian, and cacao, which were sought after by other civilizations. The trade networks facilitated not only economic prosperity but also cultural exchanges, allowing for the spread of ideas, technologies, and artistic styles.

Members of the middle class often enjoyed a better standard of living compared to the lower classes, as their skills and trade activities provided them with more resources and opportunities. However, their social status was still subordinate to the elite class, and they were often dependent on the favor of the rulers for their economic success.

The Lower Class: Farmers and Laborers

The lower class in Olmec society primarily consisted of farmers and laborers, who formed the backbone of the civilization. This class was responsible for the agricultural production that sustained the population and supported the elite and middle classes.

Farmers in the Olmec civilization practiced a form of agriculture that was adapted to the region's diverse environments. They cultivated staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which were essential for their diet. The Olmecs also engaged in techniques like slash-and-burn agriculture, which allowed them to clear land for cultivation. Despite the hard work and labor-intensive nature of farming, the lower class faced numerous challenges, including dependence on the seasons and the impact of natural disasters.

Laborers, on the other hand, were often employed in various capacities, including construction, transportation, and other manual tasks. They played a crucial role in the creation of monumental architecture and the maintenance of urban centers. The labor force was likely a mix of free workers and those who may have been bound to service for economic or social reasons.

The lower class had limited social mobility, as their status was largely determined by their economic contributions and the whims of the elite. However, their labor was indispensable for the functioning of Olmec society, and their efforts provided the foundation upon which the civilization thrived.

Interactions Between Classes

The interactions between the different social classes in Olmec civilization were complex and multifaceted. Despite the clear hierarchical structure, there were instances of collaboration and mutual dependence. The elite class relied on the agricultural output of the lower class to sustain their lifestyle and maintain their power. In return, the lower class benefited from the protection and governance provided by the rulers.

Trade played a significant role in the interactions between classes. Artisans and merchants from the middle class collaborated with the elite to create and distribute goods, while farmers supplied the necessary resources to support both the middle and elite classes. This interdependence fostered a sense of community, despite the social hierarchies in place.

Moreover, cultural practices, such as religious rituals and festivals, brought people from different classes together. These events allowed for the display of wealth and power by the elite, while also providing opportunities for the lower classes to participate in the communal life of the society. Such interactions contributed to the cohesion of Olmec civilization and reinforced the social structure that defined it.

Conclusion

The class structure of Olmec civilization was a reflection of its complex society, characterized by distinct roles and responsibilities for each social class. The elite class, with its rulers and priests, held power and influence over the populace, while the middle class of artisans and merchants contributed to the economy and cultural exchanges. The lower class of farmers and laborers provided the essential labor that sustained the civilization. Understanding this class structure offers insight into the dynamics of Olmec society and highlights the interdependence that existed among its various classes.

Labor and Economic Activities in Olmec Society

The Olmec civilization, often referred to as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, flourished in what is now southern Mexico from approximately 1400 to 400 BCE. This civilization was not only advanced in their art and religion but also in their economic structures and labor practices, which played a crucial role in shaping their societal hierarchy. Understanding the labor and economic activities in Olmec society reveals how these elements contributed to the development of their complex social structure.

Agricultural Practices and Crop Cultivation

Agriculture was the backbone of the Olmec economy, providing sustenance and a means for trade. The Olmecs employed a variety of agricultural techniques that allowed them to thrive in the fertile river valleys of the Gulf Coast region. Key crops included maize, beans, squash, and root vegetables. The cultivation of these staples was vital for sustaining the population and supporting the elite class, which relied heavily on surplus food for their status and rituals.

One of the most significant agricultural practices of the Olmecs was the use of slash-and-burn techniques. This method involved cutting down vegetation and burning it to clear land for farming. The ashes enriched the soil with nutrients, leading to increased crop yields. Furthermore, the Olmecs practiced crop rotation and intercropping, which helped maintain soil fertility and reduce pest infestations. These practices showcased their advanced understanding of agricultural science and allowed for efficient land use in their environment.

In addition to maize, which was sacred to many Mesoamerican cultures, the Olmecs cultivated various varieties of beans and squash that complemented the maize diet. The combination of these three crops, known as the "Mesoamerican triad," provided a balanced diet for the Olmec people, enabling population growth and the development of specialized labor.

Trade Networks and Economic Exchange

The Olmec civilization established extensive trade networks that facilitated the exchange of goods and resources across vast distances. The region's abundant natural resources, particularly jade, obsidian, and rubber, were highly sought after by neighboring cultures. As a result, the Olmecs became key players in the regional economy, trading their luxury goods for raw materials, food, and other necessities.

Trade was not only a means of economic exchange but also a way to forge political alliances. The Olmecs participated in a complex web of trade relationships that extended to other Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya and Zapotecs. This network allowed for the flow of ideas, technologies, and cultural practices, further enriching Olmec society and influencing the development of subsequent civilizations.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Olmecs utilized a variety of trade routes, including rivers and overland paths. The rivers facilitated the transport of heavy goods, while overland routes allowed for the exchange of perishable items. The Olmecs likely employed canoes for river transport, which enabled them to trade efficiently with distant communities.

Role of Labor in Social Hierarchy

The division of labor in Olmec society was closely tied to their social hierarchy, with distinct roles assigned to different classes. The elite class, composed of rulers and priests, held power and controlled resources, while the middle and lower classes engaged in various forms of labor. This stratification was essential for maintaining social order and facilitating economic activities.

The elite class not only managed agricultural production but also oversaw trade and labor practices. They were responsible for making decisions related to resource allocation and the organization of labor. This control allowed them to maintain their status and ensure the prosperity of their society.

Artisans and merchants formed the middle class, playing a crucial role in the Olmec economy. Artisans were skilled workers who produced goods such as pottery, textiles, and stone carvings. Their craftsmanship was highly valued, and their creations often served religious or ceremonial purposes. Merchants, on the other hand, acted as intermediaries in trade, facilitating the exchange of goods both locally and regionally. The prosperity of these middle-class individuals contributed to the overall wealth of Olmec society and further solidified the power of the elite.

At the base of the social hierarchy were farmers and laborers, who formed the backbone of Olmec agriculture and construction. These individuals engaged in the daily tasks necessary for food production and the maintenance of urban centers. Despite their essential contributions, they often lived under the control of the elite, receiving limited rewards for their labor. This disparity in wealth and status highlighted the social inequalities present within Olmec society.

The labor system in Olmec civilization was not merely a means of economic production but also a reflection of their cultural values. The Olmecs revered hard work and craftsmanship, which were seen as honorable pursuits. This cultural perspective likely influenced their labor practices and the way they organized their society.

Economic Innovations and Their Impact

The Olmec civilization is credited with several economic innovations that laid the groundwork for future Mesoamerican societies. One of the most significant advancements was the development of a form of currency, likely based on cacao beans or other valuable commodities. This system of exchange facilitated trade and allowed for greater economic complexity, as it provided a standardized method of valuing goods and services.

Moreover, the Olmecs are believed to have pioneered large-scale agricultural projects, such as irrigation systems, that enhanced their ability to cultivate crops in varying environmental conditions. These innovations not only increased agricultural productivity but also demonstrated an advanced understanding of engineering and resource management.

Through their economic activities, the Olmecs established a legacy of trade and labor practices that influenced subsequent cultures in the region. Their innovations in agriculture, trade, and labor organization set the stage for the rise of more complex societies, such as the Maya and Aztecs, who would build upon the foundations laid by the Olmecs.

Conclusion

The labor and economic activities of the Olmec civilization were integral to their social structure and overall success. Through advanced agricultural practices, extensive trade networks, and a well-defined social hierarchy, the Olmecs created a thriving society that set the stage for future Mesoamerican cultures. The interplay between labor, class structure, and economic exchange highlights the complexity of Olmec civilization and its lasting impact on the history of Mexico and beyond.

As we study the Olmecs, it is essential to recognize the significance of their contributions to the development of Mesoamerican societies and the ways in which their economic systems shaped the cultural landscape of the region.