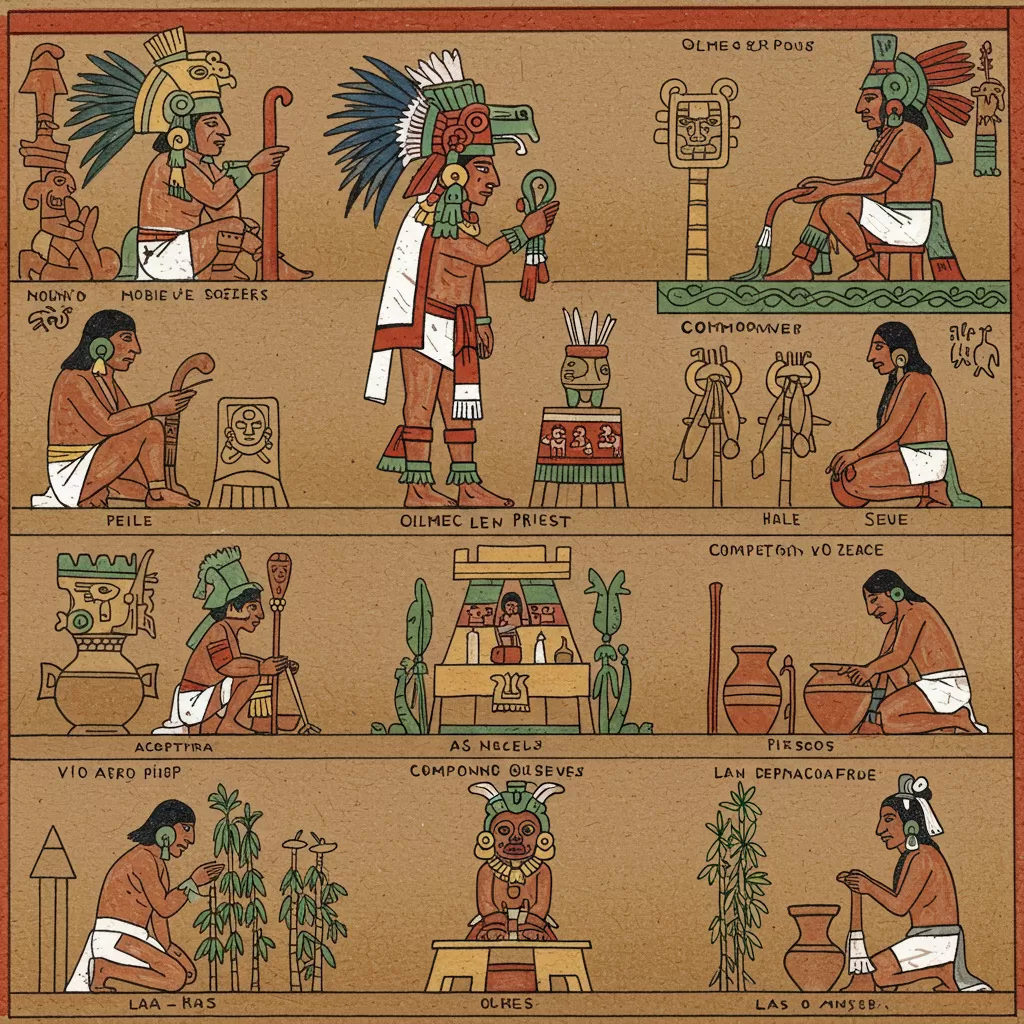

Olmec Social Hierarchies: Nobles, Priests, and Commoners

The Olmec civilization, often regarded as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, laid the foundation for many subsequent societies through its complex social structures and cultural innovations. Central to understanding the Olmec legacy is a deep dive into the social hierarchies that defined their way of life. These hierarchies were not merely a reflection of power dynamics but were intricately woven into the fabric of Olmec culture, influencing everything from governance to religious practices.

Nobles, priests, and commoners each played essential roles within this hierarchy, creating a society that balanced political authority, spiritual leadership, and everyday labor. Nobles wielded considerable political and economic power, while priests upheld the spiritual beliefs that bound the community together. Meanwhile, commoners, often overlooked, contributed significantly to the social and cultural landscape, participating in both labor and religious rituals. Understanding these roles provides a clearer picture of how the Olmec civilization thrived and influenced future cultures in the region.

Understanding Olmec Social Hierarchies

The Olmec civilization, often regarded as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, flourished between 1400 and 400 BCE in what is now southern Mexico. This ancient civilization laid the groundwork for future cultures in the region, including the Maya and Aztecs. Central to the Olmec society was its complex social hierarchy, which shaped the political, economic, and spiritual life of the community. Understanding the social hierarchies of the Olmec civilization provides insight into how power, resources, and cultural practices were organized and maintained.

Definition and Importance of Social Hierarchies

Social hierarchy refers to the structured ranking of individuals within a society based on various factors such as wealth, power, occupation, and social status. In the context of the Olmec civilization, social hierarchies were crucial for maintaining order and organization. They delineated roles and responsibilities, established norms for interaction, and facilitated the governance of the community.

The importance of social hierarchies in Olmec society can be seen in several key aspects:

- Political Structure: The existence of a ruling class allowed for centralized governance, which was essential for managing the complexities of Olmec cities.

- Economic Control: Social hierarchies influenced access to resources, land ownership, and trade, ultimately shaping the economic landscape.

- Cultural Identity: The stratification of society contributed to a shared cultural identity, as different classes engaged in distinct cultural practices and rituals.

In essence, social hierarchies were not merely a reflection of inequality; they were instrumental in the functioning and sustainability of Olmec civilization. The roles of nobles, priests, and commoners were interdependent, creating a cohesive societal structure that facilitated both governance and cultural expression.

Historical Context of Olmec Civilization

The Olmec civilization emerged in a region characterized by rich resources and strategic trade routes. The Gulf Coast of Mexico, particularly in present-day Veracruz and Tabasco, provided fertile land for agriculture and a wealth of materials for crafting and trade. The Olmec are renowned for their colossal stone heads and intricate jade carvings, which reflect their artistic sophistication and societal organization.

The rise of the Olmec civilization can be traced back to the development of agriculture, which allowed for the establishment of permanent settlements. With the surplus of food, populations grew, leading to more complex social structures. The Olmec society is believed to have been one of the first in Mesoamerica to organize itself into a stratified hierarchy, with distinct classes that played specific roles in governance, economics, and religion.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Olmec had developed city-states, with San Lorenzo and La Venta being among the most significant. These urban centers served as political and religious hubs, where elites could exert influence over surrounding regions. The monumental architecture and artifacts found in these sites indicate a high degree of social organization and the central role of the elite in Olmec society.

The historical context in which the Olmec civilization thrived is crucial for understanding their social hierarchies. The need for order and control in rapidly growing urban centers necessitated a clear and defined structure, which in turn shaped the interactions between different social classes.

The Roles of Nobles in Olmec Society

The Olmec civilization, recognized as one of the earliest complex societies in Mesoamerica, flourished in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico from about 1200 BCE to 400 BCE. Within this civilization, social hierarchies played a crucial role in organizing society and determining the relationships among its members. Among these hierarchies, the nobles occupied a prominent position, wielding significant political, economic, and cultural influence. Understanding the multifaceted roles of nobles in Olmec society is essential for comprehending the complexity of their civilization and the dynamics that sustained it.

Political Power and Governance

Nobles in Olmec society were not merely elite individuals; they functioned as the ruling class responsible for governance and political organization. Their authority derived from a combination of hereditary privilege, wealth, and the ability to maintain order within their communities. Political power among the Olmecs was often centralized, with noble families leading city-states such as San Lorenzo and La Venta. These city-states were structured around a theocratic model where rulers, often priests and nobles, governed with divine justification, intertwining religion and politics.

The political landscape of the Olmecs was characterized by a hierarchy where the most powerful nobles held significant sway over decision-making processes. They were responsible for establishing laws, organizing labor for large-scale construction projects, and leading military campaigns to defend their territories or expand their influence. The elites often presided over councils and assemblies where critical issues were debated, showcasing their leadership and the importance of consensus in governance.

Moreover, the political power of the nobles was reinforced through ritualistic practices. They participated in ceremonies that legitimized their authority, often portraying themselves as intermediaries between the gods and the people. This connection to the divine not only solidified their power but also created a strong social cohesion among the populace, who were likely to support their leaders due to perceived divine backing.

Economic Influence and Control of Resources

The economic role of nobles in Olmec society was equally significant. Nobles controlled access to vital resources, including agricultural land, trade routes, and luxury goods. Their wealth was often derived from extensive farming, where they oversaw the production of staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash. This agricultural surplus was crucial for sustaining the population and supporting the social structure of the Olmec civilization.

Additionally, nobles were heavily involved in trade networks that extended beyond their immediate regions. The Olmec civilization was a hub for trade, facilitating the exchange of goods such as jade, obsidian, and ceramics. Nobles acted as intermediaries in these trade transactions, further enhancing their economic power and influence. They established connections with other Mesoamerican cultures, allowing for the flow of ideas, goods, and cultural practices that enriched Olmec society.

The economic influence of nobles was also evident in their patronage of artisans and craftsmen. By sponsoring the production of art and monumental architecture, they not only displayed their wealth but also reinforced their status. Artifacts such as colossal stone heads and intricately carved jade pieces serve as testaments to the wealth and artistry fostered by noble patronage. This cultural investment played a crucial role in establishing Olmec identity and perpetuating the civilization's legacy.

Cultural Contributions and Patronage

The cultural contributions of nobles in Olmec society extended beyond mere economic influence. They played a pivotal role in the development of Olmec art, religion, and social customs. Nobles were often patrons of monumental architecture and artistic expression, commissioning grand structures and intricate artworks that reflected their power and piety.

One of the most striking aspects of Olmec culture is its artistic legacy, which was significantly shaped by noble patronage. The Olmecs are renowned for their colossal heads sculpted from basalt, which are believed to represent rulers or important figures. These monumental creations were not only symbols of power but also served as a means of connecting the living with their ancestors, emphasizing the importance of lineage and memory in Olmec society.

In addition to monumental art, nobles were instrumental in religious practices. They conducted rituals and ceremonies that reinforced the social hierarchy and the community's beliefs. The Olmecs had a complex pantheon of deities, and nobles often acted as high priests, performing sacrifices and other sacred rites to appease the gods. This dual role of political and religious authority meant that nobles held considerable sway over the spiritual well-being of their communities, further solidifying their status.

Furthermore, the system of education and cultural transmission within the Olmec society was heavily influenced by the nobility. They ensured that knowledge, traditions, and religious practices were passed down through generations, creating a shared cultural identity among the Olmec people. This cultural continuity was vital for the cohesion of Olmec society, especially in the face of external pressures and changing circumstances.

In summary, the roles of nobles in Olmec society were multifaceted, encompassing political power, economic influence, and cultural contributions. Their governance was deeply intertwined with religious practices, and they played a crucial role in shaping the Olmec identity through art and tradition. The legacy of these nobles is evident in the archaeological record and continues to be a focal point for understanding the complexities of one of Mesoamerica’s earliest civilizations.

The Function of Priests in Olmec Culture

The Olmec civilization, often referred to as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, flourished in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico from approximately 1200 to 400 BCE. Within this intricate society, the role of priests was paramount, serving as mediators between the divine and the earthly realms. Their influence permeated various aspects of Olmec life, including religion, politics, and culture. This section will delve into the multifaceted functions of priests in Olmec society, exploring their religious practices and beliefs, their ceremonial duties, and their interactions with both the nobility and commoners.

Religious Practices and Beliefs

Religion was the cornerstone of Olmec society, and priests were the key figures in maintaining the spiritual fabric of their community. The Olmecs practiced a polytheistic faith, worshipping a pantheon of gods, each associated with natural elements, agriculture, and fertility, among other aspects of life. Central to their belief system was the idea that the cosmos was a living entity, and the priests acted as conduits between the people and these supernatural forces. Through rituals, they sought to ensure harmony and balance in the world.

Olmec priests were responsible for conducting various religious ceremonies, which often involved elaborate offerings and sacrifices. These ceremonies were not merely expressions of devotion but were believed to be essential for securing the favor of the gods. The Olmecs revered deities such as the jaguar, a symbol of strength and power, and the maize god, who represented fertility and sustenance. To honor these deities, priests would perform rituals that included the use of incense, music, and dance, creating a sensory experience meant to inspire reverence and connection to the divine.

Additionally, the Olmec belief system included the concept of the "blood" of the earth, which emphasized the importance of sacrifice. Rituals involving bloodletting were common, where priests would pierce their skin to offer blood to the gods. This act was believed to nourish the earth and maintain the balance of life. Such practices highlight the deep interconnection between the spiritual and physical realms in Olmec culture.

Rituals and Ceremonial Duties

The ceremonial calendar of the Olmecs was filled with significant events that marked agricultural cycles, seasonal changes, and important life milestones. Priests played a crucial role in orchestrating these rituals, which served both religious and social functions. Major festivals often coincided with the planting and harvesting of crops, underscoring the importance of agriculture to the Olmec way of life.

One of the most notable rituals was the "ballgame," which held both recreational and religious significance. This game was not only a competitive sport but also a ceremonial event believed to reflect the struggle between life and death, and the duality of existence. Priests would officiate these events, interpreting the outcomes as omens or messages from the gods. The ballgame's connection to religious beliefs illustrates how intertwined social activities were with spiritual practices.

Moreover, the construction of ceremonial centers, such as La Venta and San Lorenzo, was directly influenced by priestly authority. These sites often featured large stone altars, sculptures, and plazas designed for public ceremonies. The layout and orientation of these centers were carefully planned to align with celestial events, reinforcing the priests' role as guardians of both spiritual and astronomical knowledge.

Interaction with Nobility and Commoners

The relationship between priests and the nobility was characterized by mutual respect and interdependence. Nobles often held political power, but their authority was legitimized through the endorsement of priests. In many cases, rulers were believed to possess divine ancestry or were seen as representatives of the gods on earth. Thus, priests played an essential role in crowning and supporting leaders, reinforcing their status and influence.

Priests and nobles collaborated in the organization of large-scale rituals and festivals, where the participation of the community was essential. These events provided an opportunity for the elite to display their wealth and power while simultaneously affirming the social order. The rituals often included processions, music, and offerings to the gods, creating a collective experience that united the community in religious devotion.

In contrast, the interaction between priests and commoners was more complex. While priests were revered figures, their authority could also be a source of tension. Commoners, who made up the majority of the Olmec population, were primarily responsible for agricultural production and labor. They participated in rituals and ceremonies but were often at the mercy of the elites and priests. However, commoners also had the opportunity to engage in religious practices, seeking blessings and support from the priests for their crops and families.

Despite the hierarchical structure of Olmec society, there were moments of social mobility. Some commoners could rise to prominence through their involvement in religious practices or by demonstrating exceptional skills in various trades. This potential for upward mobility created a dynamic social environment where interactions between priests, nobles, and commoners were not solely defined by rigid boundaries.

The Influence of Priests Beyond Religion

The influence of priests in Olmec society extended beyond the realm of religion. They were also key figures in the administration of the community, often involved in decision-making processes related to resource allocation and conflict resolution. Their spiritual authority granted them a unique position, allowing them to mediate disputes and provide guidance to both nobles and commoners.

Education and knowledge were also under the purview of priests. They were the keepers of sacred knowledge, including astronomical observations, agricultural techniques, and healing practices. This knowledge was transmitted through oral traditions and rituals, ensuring the continuity of cultural practices. The priests' role as educators solidified their importance in the community, as they equipped future generations with the skills and understanding necessary for survival and prosperity.

Moreover, the artistic expressions of the Olmec civilization were often influenced by religious iconography. Priests were likely involved in the commissioning of monumental art, such as colossal heads and jade figurines, which depicted deities and were used in various rituals. These artistic endeavors not only served a religious purpose but also reinforced the social hierarchies within Olmec society, showcasing the power of both priests and nobles.

Summary Table of Priest Functions in Olmec Culture

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| Religious Practices | Conducting rituals, offering sacrifices, and maintaining cosmic balance. |

| Ceremonial Duties | Orchestrating festivals, officiating significant events, and overseeing public rituals. |

| Interaction with Nobility | Supporting rulers, legitimizing power, and collaborating on ceremonial events. |

| Engagement with Commoners | Facilitating community participation in rituals and providing spiritual support. |

| Cultural Influence | Preserving sacred knowledge, influencing art, and shaping community values. |

The function of priests in Olmec culture was a complex tapestry of religious devotion, social influence, and cultural preservation. Their roles were not limited to conducting rituals and overseeing ceremonies; they were integral to the very fabric of Olmec society. Through their spiritual authority, priests connected the community to the divine, engaged with the ruling elite, and fostered cultural continuity. Understanding their multifaceted roles provides valuable insight into the intricacies of Olmec civilization and its enduring legacy in the history of Mesoamerica.

The Life of Commoners in Olmec Society

The Olmec civilization, often referred to as the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, flourished in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico from approximately 1400 to 400 BCE. While much attention has been focused on the elite classes, such as the nobles and priests, the commoners played a crucial role in the fabric of Olmec society. Understanding their daily lives, occupations, social mobility, and their contributions to religious and cultural practices offers insight into the complexities of Olmec civilization.

Daily Life and Occupations

The life of commoners in Olmec society was characterized by a blend of labor, community engagement, and adherence to cultural values. Most commoners were engaged in agriculture, which was the backbone of the Olmec economy. They cultivated crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which were staples of their diet. The fertile land along the Gulf Coast provided ideal conditions for farming, and the Olmec developed sophisticated agricultural techniques, including the use of raised fields and irrigation systems.

Besides agriculture, commoners were also involved in various crafts and trades. Artisans produced pottery, textiles, and stone tools, while others might have worked as fishermen or hunters. The Olmec are known for their exquisite jade carvings and colossal stone heads, indicating that skilled labor was valued and likely supported by a network of commoners who specialized in these areas. The craftwork not only served practical purposes but also had cultural significance, as objects created by commoners were often used in religious rituals and elite ceremonies.

In the urban centers, such as San Lorenzo and La Venta, commoners lived in simple structures made of perishable materials. Their homes were typically small and modest, contrasting sharply with the grand structures of the elites. However, these residential areas were often organized around community spaces where social and cultural activities took place, reflecting a strong sense of community among the commoners.

Social Mobility and Opportunities

Social mobility in Olmec society was somewhat limited compared to other civilizations, but commoners did have opportunities to improve their status. Through hard work, skill, and sometimes through marriage alliances, individuals could rise in social standing. For instance, a talented artisan could gain recognition and possibly become a favored craftsman for the elite, leading to better living conditions and greater influence within the community.

The Olmec also had a system of tribute, where commoners contributed a portion of their agricultural produce or crafted goods to the nobles and priests. While this might seem burdensome, it provided commoners with the opportunity to engage with the ruling class, fostering relationships that could enhance their social standing. In some instances, successful commoners might gain enough wealth to become patrons of artisans, thereby elevating their status further.

However, the hierarchical nature of Olmec society meant that these advancements were often limited and dependent on the goodwill of the elite. The majority of commoners remained in the lower strata of the social hierarchy, which was governed by strict class distinctions. Nonetheless, the resilience and adaptability of commoners allowed them to navigate these challenges, contributing to the overall stability and continuity of Olmec society.

The Role of Commoners in Religious and Cultural Practices

Religion was a central aspect of Olmec life, and commoners played a vital role in the religious and cultural practices of their society. They participated in communal rituals, ceremonies, and festivals, which were often organized by the elite but required the involvement of the entire community. These events fostered a sense of identity and belonging among commoners, reinforcing their connection to the Olmec culture.

Commoners often engaged in agricultural rituals to ensure a bountiful harvest, which included offerings to deities and the performance of specific rites. These practices underscored the significance of their role in the agricultural economy and highlighted their relationship with the gods. The Olmec pantheon included various deities associated with maize, rain, and fertility, all of which were crucial for sustaining their agrarian lifestyle.

Moreover, commoners participated in the construction of ceremonial centers and monuments, which were integral to Olmec religious life. The labor involved in building temples and public spaces, such as plazas, demonstrated their contributions to the cultural heritage of the Olmec civilization. These sites often served as venues for rituals and gatherings, reinforcing the communal bonds among commoners.

In addition to agricultural and ceremonial practices, commoners also contributed to oral traditions, storytelling, and the transmission of cultural knowledge. They played a crucial role in passing down myths, legends, and historical narratives that shaped Olmec identity. This cultural transmission was vital for maintaining the continuity of Olmec beliefs and practices, even as the civilization evolved over time.

Conclusion

The life of commoners in Olmec society was multifaceted and essential to the overall functioning of this early civilization. Their daily activities in agriculture and crafts, coupled with their participation in religious and cultural practices, illustrate the integral role they played in sustaining the Olmec way of life. While the hierarchies established by the elite often constrained their social mobility, commoners found ways to navigate and influence their circumstances, contributing to the resilience and richness of Olmec culture.

As we study the Olmec civilization, it is crucial to recognize the contributions of commoners, as they represent the foundation upon which the complexities of Olmec society were built. Their efforts and traditions not only shaped their own lives but also laid the groundwork for future Mesoamerican civilizations that followed.