Maya Social Structure: Nobles, Commoners, and Slaves

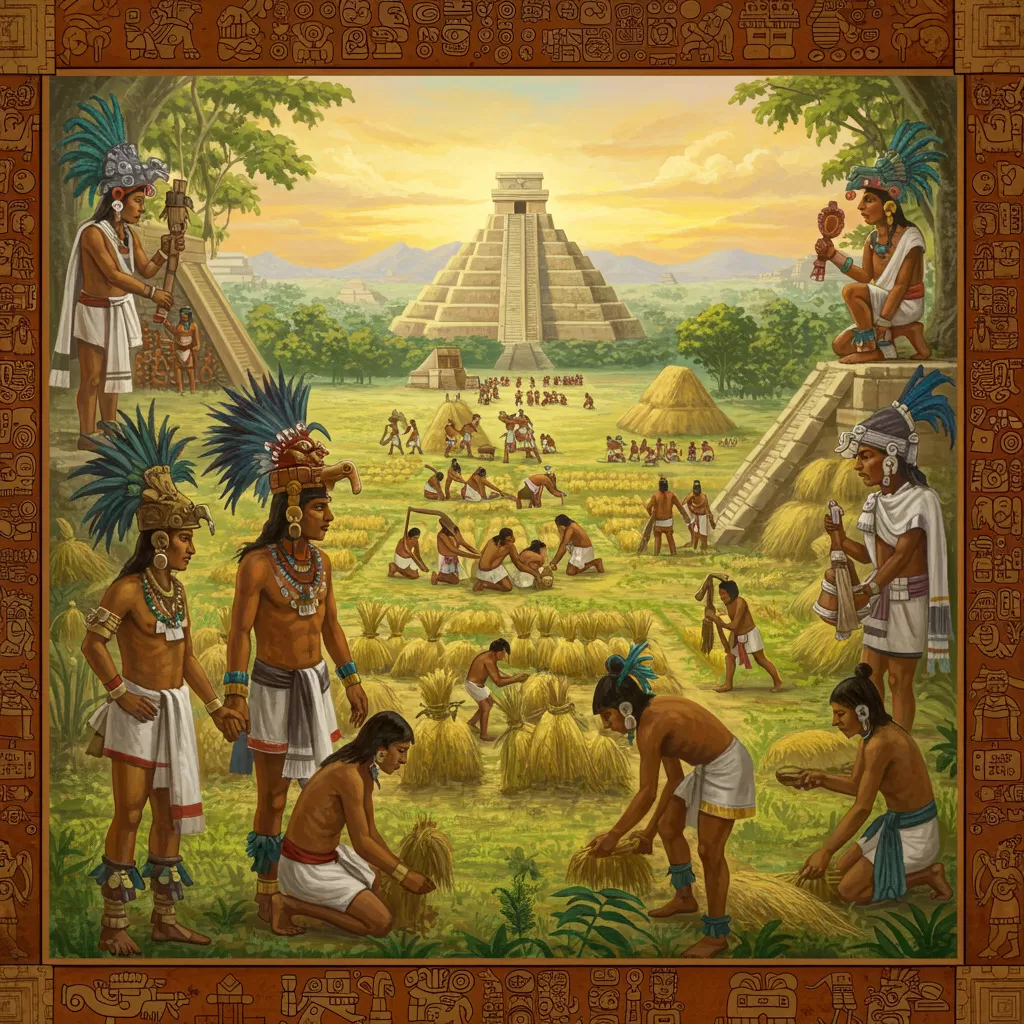

The Maya civilization, renowned for its impressive achievements in architecture, mathematics, and astronomy, was also characterized by a complex social structure that played a pivotal role in its development. At the heart of this society were distinct social classes, each with specific roles, responsibilities, and influences that shaped the everyday lives of the Maya people. Understanding this intricate hierarchy is crucial to appreciating the dynamics of one of the most fascinating ancient cultures in history.

The social organization of the Maya encompassed a diverse range of individuals, from the powerful nobles who governed and influenced cultural practices, to the commoners who formed the backbone of the economy, and the slaves who were often seen as property. Each class contributed uniquely to the fabric of Maya society, creating a rich tapestry of interactions and relationships that defined their civilization. As we delve deeper into the roles of these groups, we will uncover how their interconnectedness not only influenced their daily lives but also determined the course of Maya history.

Understanding Maya Social Structure

The social structure of the Maya civilization was multifaceted and profoundly influenced by historical, cultural, and economic factors. The Maya, known for their advanced architectural, astronomical, and mathematical achievements, had a complex hierarchy that dictated the roles and responsibilities of individuals within society. Understanding this structure is crucial to appreciating how the Maya lived, governed, and interacted with one another, as well as acknowledging the legacies they left behind.

Historical Context of Maya Civilization

The Maya civilization flourished in Mesoamerica, particularly in the regions that are now southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. The civilization's history can be divided into several periods: the Preclassic (2000 BCE to 250 CE), the Classic (250 to 900 CE), and the Postclassic (900 to 1500 CE). Each period saw significant developments in culture, politics, and society.

During the Preclassic period, the Maya began to form agricultural communities, which set the foundation for more complex societies. By the Classic period, the Maya had established city-states, each ruled by a king or a noble elite. These city-states, such as Tikal, Palenque, and Calakmul, engaged in trade, warfare, and alliances, leading to a dynamic political landscape.

The Postclassic period saw changes in political organization and social structures, influenced by external factors such as the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century. This period was characterized by a decline in the power of individual city-states and an increase in regional centers. Despite these shifts, the core elements of Maya society, including their hierarchical structure, remained intact until the arrival of colonizers.

Importance of Social Hierarchy

The Maya social hierarchy was essential for maintaining order and stability within their civilization. It was structured like a pyramid, with the elite at the top and the commoners and slaves at the bottom. This hierarchy was not merely a reflection of wealth but was also tied to lineage, political power, and religious status.

At the top of the social structure were the nobles, who held significant power and influence. They were responsible for governance, religious practices, and warfare. Below them were the commoners, who made up the majority of the population and were engaged in various economic activities. At the very bottom were the slaves, who had little to no rights and were often used for labor-intensive tasks.

The social hierarchy served several purposes. It provided a framework for governance, ensuring that the nobility had the authority to make decisions that affected the entire society. It also created a sense of identity and belonging among the different classes, reinforcing the idea that each class had its role to play in the larger community. Understanding this hierarchy is crucial for analyzing the complexities of Maya life and the interactions between different social groups.

The Noble Class in Maya Society

The noble class was a cornerstone of Maya society, wielding power and influence across various domains, including politics, religion, and culture. Nobles were typically from elite families with established lineages, and their status was often inherited. This class included kings, priests, and high-ranking officials who played pivotal roles in shaping the direction of Maya city-states.

Roles and Responsibilities of Nobles

Nobles in Maya society had defined roles that extended beyond mere governance. They were responsible for the administration of their city-states, overseeing everything from political decisions to economic policies. This included managing resources, organizing labor for large construction projects, and ensuring the well-being of their subjects.

Religiously, nobles acted as intermediaries between the gods and the people. They conducted elaborate rituals and ceremonies, which were vital for maintaining the favor of the deities. This religious authority contributed to their power, as the populace believed that the nobles had the divine right to rule. Nobles also played key roles in warfare, leading armies into battle to expand their territories or defend their city-states against outside threats.

Nobility's Influence on Governance

The governance of Maya city-states was characterized by a theocratic system where political and religious power were intertwined. Nobles held significant sway over decision-making processes, often convening councils to deliberate on matters of importance. These councils consisted of noble families, each representing different sectors of society.

The influence of the nobility extended beyond local governance. They also participated in regional politics, forming alliances with other city-states to enhance their power. Marriages between noble families were strategic, designed to solidify alliances and create bonds of loyalty. This political maneuvering was instrumental in shaping the historical trajectory of the Maya civilization.

Cultural Contributions of the Elite

The contributions of the noble class to Maya culture were immense. They were patrons of the arts, commissioning monumental architecture, intricate carvings, and vibrant murals that depicted their achievements and religious beliefs. Notable examples include the elaborate temples and palaces found in Tikal and Palenque, which stand as testaments to their artistic and architectural prowess.

The nobles also played a crucial role in the preservation and advancement of Maya knowledge. They were often educated in mathematics, astronomy, and writing, which allowed them to contribute to the development of the Maya calendar and hieroglyphic writing system. This intellectual legacy has had a lasting impact on the study of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations.

Commoners and Their Position in Society

Commoners made up the bulk of the Maya population and were essential to the functioning of society. They were engaged in various economic activities, including agriculture, trade, and craftsmanship. While they had fewer privileges than the nobles, commoners occupied a crucial position in the social structure.

Daily Life of Commoners

The daily life of commoners revolved around agriculture, as they cultivated staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash. Farming was labor-intensive and required cooperation among families and communities. Most commoners lived in simple thatched-roof houses made from local materials, which provided modest shelter but were functional for their needs.

In addition to agriculture, commoners participated in trade, both within their communities and with neighboring city-states. They exchanged goods such as textiles, pottery, and foodstuffs, facilitating economic interactions that enriched their lives. Festivals and markets provided opportunities for socialization and cultural expression, where commoners could showcase their crafts and celebrate community milestones.

Economic Activities and Livelihoods

The economic activities of commoners were diverse and essential for the sustainability of Maya society. Agriculture was the backbone of the economy, but many commoners also engaged in specialized crafts, such as pottery, weaving, and tool-making. These crafts were often passed down through generations and were integral to Maya culture.

Commoners also played a significant role in construction projects, particularly in the building of temples and public structures. They were often organized into work crews, which reflected a communal approach to labor. This not only fostered a sense of community but also ensured that large-scale projects were completed efficiently.

Social Mobility and Opportunities

While the social hierarchy was rigid, there were limited opportunities for social mobility among commoners. Exceptional skills in trade, craftsmanship, or military service could allow some individuals to rise in status, potentially gaining favor with the nobility. In some cases, successful merchants could amass wealth, allowing them to marry into noble families, thereby enhancing their social standing.

Additionally, participation in warfare could provide commoners with opportunities for recognition and advancement. Successful warriors were often rewarded with land or titles, which could elevate their status within society. However, these instances were relatively rare, and the majority of commoners remained within their defined social roles throughout their lives.

Slavery in Maya Civilization

Slavery was a significant aspect of Maya society, contributing to the economic and social fabric. Slavery in the Maya context was complex and varied, with different origins and roles for slaves within the community.

Origins and Types of Slavery

Slaves in Maya society were typically individuals captured during warfare, but they could also be born into slavery or sold into servitude to pay off debts. The status of slaves was not permanent, as some could earn their freedom through service, monetary compensation, or favorable treatment from their owners.

There were various types of slaves, including household slaves who performed domestic tasks, agricultural slaves who worked on farms, and those employed in construction. The treatment of slaves varied considerably, with some enjoying relatively humane conditions while others faced harsh labor and punishment.

Roles of Slaves in Maya Society

Slaves played an essential role in the economy of the Maya civilization. Their labor was critical for agricultural production, particularly in large-scale farming operations owned by nobles. Slaves often worked alongside commoners, contributing to the production of staple crops and luxury goods.

In addition to agricultural work, slaves were also employed in domestic settings, performing tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Some skilled slaves could even specialize in crafts, contributing to the production of textiles and pottery.

Impact of Slavery on the Economy and Culture

The institution of slavery had a profound impact on Maya society, contributing to the economic prosperity of the elite and shaping cultural practices. The labor provided by slaves allowed nobles to engage in politics, warfare, and religious activities without the burden of manual labor.

Moreover, the presence of slavery influenced social norms and values. It reinforced the existing social hierarchy, as the elite depended on the subjugation of others for their wealth and power. The cultural ramifications of slavery can still be seen in the collective memory and identity of modern Maya communities, which are shaped by their historical experiences.

The Noble Class in Maya Society

The noble class, or the elite of the Maya civilization, played a critical role in shaping the political, economic, and cultural landscapes of their society. This social stratum was not merely a privileged group but a complex hierarchy with distinct roles, responsibilities, and influence. Understanding the noble class provides valuable insights into the broader structure of Maya society and its various components. This section delves into the roles and responsibilities of nobles, their influence on governance, and their cultural contributions.

Roles and Responsibilities of Nobles

The noble class in Maya society was composed of high-ranking individuals, including kings, priests, and military leaders. These nobles were crucial in maintaining order and governance within their city-states. Their roles extended beyond mere governance; they were also the custodians of religious practices, culture, and rituals, which were integral to Maya life.

Kings, often referred to as "Ajaw," were at the pinnacle of the noble class. They were seen as divine figures, mediating between the gods and the people. Their responsibilities included making crucial decisions affecting their city-states, leading armies in warfare, and conducting religious ceremonies to appease the gods. The power of an Ajaw was often legitimized through lineage, as many claimed descent from the gods or legendary figures, thus reinforcing their status and authority.

Priestly nobles also held significant power, responsible for conducting rituals, interpreting omens, and maintaining the calendar. Their role was essential to agricultural cycles, as they orchestrated ceremonies to ensure favorable weather and abundant harvests. This connection to the divine further solidified their status within society, as they were seen as essential for the welfare of the community.

Military leaders, another subset of the noble class, were vital in expanding and protecting the territories of the city-states. They were responsible for organizing and leading armies during conflicts, which were common in the competitive landscape of the Maya civilization. Victories in warfare not only expanded territorial boundaries but also enhanced the status of the nobles involved, as successful leaders were often rewarded with land, tribute, and prestige.

The roles of nobles were intertwined with their responsibilities towards the common people. Nobles were expected to provide protection and support to their subjects, ensuring the welfare of the community. In return, commoners were required to pay tribute, often in the form of labor or agricultural produce, which reinforced the economic foundations of the noble class.

Nobility's Influence on Governance

The governance of Maya city-states was highly influenced by the noble class. Unlike centralized empires, the Maya civilization was composed of multiple city-states, each with its own rulers and governance systems. The noble class played a crucial role in the political dynamics of these city-states, often forming councils that advised the king and participated in decision-making processes.

Political power was often hereditary, but it was not solely determined by birthright. Nobles could gain influence through military achievements, wealth accumulation, and strategic marriages. This fluidity allowed for some degree of social mobility, although it remained limited. The noble class often negotiated power through alliances, both within and between city-states, thereby shaping the political landscape of the Maya civilization.

The role of nobles in governance also extended to law and order. They were responsible for upholding justice within their domains, which included resolving disputes and enforcing laws. Nobles often acted as judges, with their decisions influenced by religious beliefs and customs. This interplay between governance, law, and religion was a defining characteristic of Maya political life.

Moreover, the nobility's influence extended to foreign relations. Nobles frequently engaged in diplomatic missions, forging alliances through marriage or trade. These relationships were vital for maintaining peace and stability, as well as for securing resources and tribute from rival city-states. The ability of nobles to navigate these political complexities was essential for the prosperity of their communities.

Cultural Contributions of the Elite

The cultural contributions of the noble class in Maya society were profound and far-reaching. Nobles were not only political leaders but also patrons of the arts, education, and religion. Their influence shaped the cultural identity of the Maya civilization and left a lasting legacy that continues to be studied today.

Art and architecture flourished under the patronage of the noble class. The construction of monumental structures, such as pyramids, temples, and palaces, was often commissioned by nobles as expressions of their power and devotion to the gods. These structures served not only a functional purpose but also acted as symbols of the divine connection between the rulers and their deities.

The noble class also played a significant role in the preservation and dissemination of knowledge. Nobles often sponsored scribes and scholars, leading to the development of complex writing systems, mathematics, and astronomy. The Maya calendar, which is renowned for its accuracy, was a product of the intellectual pursuits encouraged by the elite. Nobles sought to understand celestial movements, which were crucial for agricultural planning and religious ceremonies.

Religious rituals and ceremonies were integral to Maya culture, and the noble class was at the forefront of these practices. Nobles conducted elaborate ceremonies that reinforced their divine authority and strengthened the community's connection to the gods. These rituals often included offerings, dances, and public displays of wealth and power, further solidifying the nobility's status within society.

The nobles' patronage of the arts extended to the creation of intricate pottery, textile weaving, and jewelry, which were often used in ceremonial contexts. These artistic expressions not only showcased the skills of artisans but also reflected the values and beliefs of Maya society. The art produced during this era is characterized by its vibrant colors, detailed iconography, and symbolic representations of gods and mythological themes.

Interactions with Other Social Classes

The relationship between the noble class and other social classes was complex and multifaceted. While nobles held significant power and privilege, their interactions with commoners and slaves were essential for the functioning of Maya society. Understanding these dynamics provides a clearer picture of the social structure as a whole.

Commoners, who made up the majority of the population, were primarily engaged in agriculture, trade, and crafts. They provided the labor necessary for the economic sustenance of the city-states, and their productivity was crucial for the well-being of the nobles. In many cases, nobles relied on commoners for tribute, which included food, textiles, and other goods. This dependency created a reciprocal relationship, albeit one heavily skewed in favor of the elite.

Despite their lower status, commoners had certain rights and privileges, including the ability to own land and participate in local governance. Some individuals could rise to prominence through exceptional achievements, such as military success or exceptional craftsmanship. However, such opportunities were rare, and the social mobility of commoners was generally limited.

Slavery in Maya society also intersected with the noble class. Slaves were typically captured during warfare, born into slavery, or sold into servitude due to debt. They performed various labor roles, including agricultural work, domestic tasks, and sometimes skilled crafts. While slaves were considered property, nobles often viewed them as valuable assets that contributed to their wealth and status.

The relationship between nobles and slaves was often marked by a lack of agency for the latter. However, there were instances where slaves could earn their freedom or improve their social status, albeit with great difficulty. This complexity highlights the stratification within Maya society and the nuanced interactions between different social classes.

The Decline of the Noble Class

The decline of the noble class in Maya civilization is a subject of significant scholarly interest. Various factors contributed to this decline, including environmental challenges, warfare, and social unrest. As the Maya civilization faced increased pressure from external and internal forces, the stability of the noble class was increasingly threatened.

Environmental factors, such as prolonged droughts and soil degradation, significantly impacted agricultural productivity. As food became scarce, competition for resources intensified, leading to conflicts between city-states and within communities. The noble class, which had relied on tribute and agricultural surplus, found its power undermined by these challenges.

Warfare also played a critical role in the decline of the noble class. The Maya civilization was characterized by frequent conflicts between city-states, leading to the rise of militaristic leaders and a shift in power dynamics. In some cases, the traditional roles of nobles were challenged as new leaders emerged from the ranks of commoners or military factions.

Social unrest, fueled by economic disparities and resource scarcity, further contributed to the decline of the nobility. As commoners struggled to survive, dissatisfaction with the elite grew, leading to revolts and uprisings. The noble class's inability to adapt to changing circumstances ultimately led to their diminished influence and power.

In summary, the noble class in Maya society was a multifaceted and influential group that played a crucial role in governance, culture, and the daily lives of the people. Their legacy is evident in the architectural marvels, artistic achievements, and complex political systems that characterized the Maya civilization. Understanding this social stratum provides a deeper appreciation for the intricacies of Maya society and its historical significance.

Commoners and Their Position in Society

The Maya civilization, which flourished from approximately 2000 BCE to the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century, was characterized by a complex social structure. While much attention is often directed towards the elite and the nobility, the role of commoners is equally critical to understanding the dynamics of Maya society. Commoners, or the majority population, played a vital role in supporting the economy and culture of the Maya civilization. This section delves into the daily lives of commoners, their economic activities, and their opportunities for social mobility, providing a comprehensive overview of their significance within the broader societal framework.

Daily Life of Commoners

The daily life of commoners in Maya society was shaped by their roles as laborers, artisans, and farmers. Most commoners were engaged in agricultural work, which was the backbone of the Maya economy. They were responsible for cultivating staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which were essential for sustenance and trade. The agricultural calendar dictated their daily routines, involving planting, tending, and harvesting crops, which required considerable labor and cooperation among community members.

In addition to farming, commoners also engaged in various crafts and trades. Many were skilled artisans who produced pottery, textiles, and tools. These goods were not only for local consumption but also for trade with other communities. The markets played a crucial role in Maya society, where commoners would gather to exchange goods, barter, and socialize. The presence of markets indicated the importance of economic activities in daily life, creating a vibrant community atmosphere.

Social interactions among commoners were often community-oriented. They participated in communal activities, such as rituals and festivals, which reinforced social bonds and cultural identity. Religion was a significant aspect of their lives; commoners would often worship deities and partake in ceremonies led by the priestly class. These rituals were integral to maintaining harmony with the gods and ensuring agricultural fertility, highlighting the interconnectedness of daily life and spirituality.

Economic Activities and Livelihoods

The economic activities of commoners were diverse and multifaceted. Agriculture was the primary occupation, but the Maya economy also included various other sectors. Commoners grew a variety of crops, including maize, which was not only a staple food but also held cultural significance. The cultivation of cacao, an important trade item, was another economic activity that provided commoners with opportunities to engage in trade.

In addition to agriculture, the Maya civilization had an intricate system of trade networks. Commoners participated in these networks by trading surplus food and handmade goods. The exchange of products facilitated economic growth and strengthened relationships between different Maya city-states. This system allowed commoners to acquire goods they could not produce themselves, fostering a sense of interdependence among communities.

Artisanship was another vital economic activity. Many commoners honed their skills in pottery, weaving, and tool-making. For instance, women often played a crucial role in textile production, creating intricate garments that showcased their cultural heritage. Artisans would sell their wares in local markets, and their products were often sought after, demonstrating that commoners could achieve a level of economic stability and recognition through their craft.

Despite their significant contributions to the economy, commoners faced various challenges. The demands of agricultural life, combined with the heavy taxation imposed by the ruling elite, often left them vulnerable to economic fluctuations. Droughts, crop failures, and warfare could result in scarcity and hardship, affecting their livelihoods and overall well-being.

Social Mobility and Opportunities

While the Maya social structure was hierarchical, opportunities for social mobility existed for commoners, albeit limited. Social mobility was often contingent upon wealth accumulation, skill proficiency, and contributions to the community. For example, a commoner who achieved success in trade or craftsmanship could amass wealth and possibly gain recognition from the elite, paving the way for a more elevated social status.

Moreover, certain avenues for social mobility were tied to education and religious roles. Some commoners could become scribes or priests, positions that granted them higher status within society. Scribes held the critical role of documenting history and rituals, which was esteemed in Maya culture. Similarly, those who served as priests could gain significant influence due to their religious authority, allowing them to transcend their commoner origins.

Marriage also played an essential role in social mobility. A commoner who married into a noble family could elevate their status, providing a pathway to the elite class. These marriages were often strategic, aimed at strengthening political alliances and enhancing social standing. Such unions exemplified how personal relationships could bridge the gap between different social strata, even if such cases were rare.

However, the barriers to full social mobility remained significant. The rigid class distinctions, reinforced by cultural norms and practices, meant that most commoners would remain within their social class. Despite their potential for upward mobility, the vast majority continued to live as laborers and artisans, contributing to the economic and cultural fabric of Maya society without necessarily achieving higher status.

Key Contributions of Commoners to Maya Society

Commoners were instrumental in shaping the Maya civilization in numerous ways. Their contributions extended beyond economic activities; they were fundamental to the cultural and social dynamics of their communities. Through their everyday lives, commoners maintained and transmitted cultural traditions, ensuring the continuity of Maya heritage.

As the backbone of the agricultural economy, commoners supported the elite class, enabling the latter to focus on governance, military endeavors, and religious activities. The surplus food produced by commoners allowed for population growth and urbanization, leading to the development of complex city-states. This interdependence between classes highlights the essential role commoners played in sustaining the overall structure of Maya society.

Furthermore, commoners contributed to the rich tapestry of Maya culture through their artistic expressions. The pottery, textiles, and tools crafted by commoners not only served practical purposes but also reflected the artistic values and beliefs of the society. These artifacts provide invaluable insights into Maya life and culture, allowing modern scholars to piece together the everyday experiences of the common people.

In conclusion, commoners were a vital part of the Maya civilization, influencing its economy, culture, and social dynamics. Their daily lives, economic activities, and potential for social mobility shaped the framework of Maya society, contributing to its complexity and richness. Understanding the role of commoners is essential for a comprehensive view of the Maya civilization and its enduring legacy.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Daily Life | Focused on agriculture, trade, and communal activities. |

| Economic Activities | Involved farming, artisan crafts, and trading in local markets. |

| Social Mobility | Limited opportunities through wealth, skill, and strategic marriages. |

| Cultural Contributions | Artistic expressions and maintenance of cultural traditions. |

Slavery in Maya Civilization

The institution of slavery in Maya civilization was a complex and multifaceted aspect of their social, economic, and cultural frameworks. Unlike the chattel slavery commonly associated with later periods in history, Maya slavery was diverse in its origins, types, and roles within society. This section aims to provide an in-depth understanding of slavery in the Maya civilization, exploring its origins, various forms, roles within the society, and the broader impact on Maya economy and culture.

Origins and Types of Slavery

The origins of slavery in Maya civilization can be traced back to various socio-economic factors. Primarily, warfare played a significant role in the acquisition of slaves. During conflicts, captured warriors and their families were often enslaved as a means of punishment or to serve the victors. This acquisition of slaves through warfare was not only a practical strategy for diminishing enemy strength but also a way to bolster one's own labor force.

Additionally, slavery could arise from economic hardship. Individuals or families facing dire economic circumstances sometimes sold themselves or their children into slavery as a means of survival. This form of slavery was often temporary, as many sought to work off their debts and regain their freedom. There are indications in various archaeological findings and codices that slavery could also be a consequence of crime; individuals convicted of certain crimes could be sentenced to slavery as a form of punishment.

Moreover, the Maya recognized several types of slaves, contributing to the complexity of the institution. One of the most common types was the slaves of war, who were often taken from rival city-states. Another category included debt slaves, who were usually individuals that entered into slavery voluntarily to pay off debts. Finally, there were also hereditary slaves, born into slavery due to their parents' status, though this was less common in Maya society compared to other ancient civilizations.

Roles of Slaves in Maya Society

Slaves in Maya society performed a variety of roles that were essential to the functioning of their communities. They were primarily used as laborers in agriculture, which was the backbone of Maya economy. Fields required constant attention, and slaves were often tasked with planting, harvesting, and processing crops such as maize, beans, and squash. This labor was crucial, especially during peak agricultural seasons when the demand for workforce surged.

In addition to agricultural labor, slaves were also employed in construction projects, which were vital for the building of temples, palaces, and other monumental architecture characteristic of Maya civilization. These projects required a large, steady workforce, and slaves provided the necessary labor force to meet these demands.

Beyond manual labor, some slaves held specialized roles within the household of elite families. They could serve as cooks, servants, or even caretakers for children. This domestic labor was crucial in maintaining the social status of the elite, who relied on the labor of slaves to sustain their lifestyles and manage their households efficiently. Notably, some slaves could even acquire skills and become artisans, though this was relatively rare and usually reserved for those who had earned a degree of trust or favor from their masters.

It's essential to note that the conditions of slavery varied significantly depending on the master and the specific circumstances. While some slaves experienced harsh treatment, others might have had relatively better living conditions, especially if they were integrated into the household of a noble family. The nuances of these experiences highlight the complexity of slavery in Maya society.

Impact of Slavery on the Economy and Culture

The institution of slavery had profound ramifications for the economy and culture of the Maya civilization. Economically, slaves provided a crucial source of labor that enabled the Maya to sustain their agricultural practices and ambitious construction projects. The reliance on slave labor allowed for greater productivity in agriculture, which, in turn, supported larger populations and facilitated trade.

Trade was a vital aspect of Maya society, and the surplus production generated by slave labor contributed to this economic system. The ability to produce surplus goods allowed Maya city-states to engage in commerce with one another and with neighboring cultures, exchanging goods such as textiles, ceramics, and precious metals. The wealth generated from trade further reinforced the hierarchical structure of society, allowing elites to consolidate power and wealth.

Culturally, the existence of slavery influenced Maya social structures and relationships. The stratification of society was evident in the way slaves were treated compared to nobles and commoners. This division not only reinforced social hierarchies but also shaped cultural attitudes towards labor, servitude, and status. In many ways, the presence of slavery underscored the values of the Maya, where status was often linked to one’s role within the social hierarchy.

Furthermore, the presence of slaves in households of the elite may have also contributed to the cultural practices and rituals of the Maya. The labor provided by slaves allowed nobles to participate in religious ceremonies and political affairs, which were critical to maintaining their societal roles. Slavery, therefore, was not merely an economic institution but also one intertwined with the cultural and spiritual fabric of Maya life.

Conclusion

In summary, slavery in Maya civilization was a complex institution with deep historical roots, manifesting in various forms and roles within society. The origins of slavery were closely tied to warfare and economic conditions, while the roles slaves played were integral to the functioning of agricultural and domestic life. The economic impact of slavery facilitated trade and supported the hierarchical structure of society, while its cultural implications shaped the values and practices of the Maya people. Understanding slavery in this context is crucial for a comprehensive view of the social structure of Maya civilization and its lasting legacy.

| Type of Slavery | Description |

|---|---|

| War Slaves | Captured during conflicts, often serving their captors. |

| Debt Slaves | Individuals who sold themselves or their family into slavery to pay off debts. |

| Hereditary Slaves | Born into slavery, typically less common than other forms. |