Maya Rituals and Ceremonies: Offerings to the Gods

The ancient Maya civilization, renowned for its remarkable achievements in architecture, mathematics, and astronomy, was equally distinguished by its rich tapestry of rituals and ceremonies. These practices were not merely cultural expressions but were deeply intertwined with their understanding of the cosmos and the divine. Through various offerings to the gods, the Maya sought to maintain harmony with the forces that governed their lives, reflecting a profound spirituality that permeated every aspect of society.

At the heart of Maya spirituality lies a complex system of beliefs that elevates rituals to an essential role within their communities. Each ceremony was meticulously planned and executed, serving as a bridge between the earthly realm and the divine. From vibrant celebrations marking the New Year to solemn rituals honoring ancestors, every act was imbued with meaning, reinforcing social bonds and cultural identity.

This exploration into Maya rituals and ceremonies invites us to delve deeper into their rich traditions, examining the types of offerings made to the gods and the significant ceremonies that shaped their spiritual landscape. By understanding these practices, we gain insight into the intricate belief system of the Maya and their enduring legacy.

Understanding Maya Rituals and Ceremonies

The Maya civilization, which flourished in Mesoamerica from approximately 2000 BCE to the arrival of Spanish colonizers in the 16th century, had a rich and complex spiritual life that was deeply intertwined with its cultural practices. Understanding Maya rituals and ceremonies requires an exploration of their historical context and the essential role that these practices played in society. This section delves into the intricacies of Maya spirituality, the significance of rituals, and how these elements shaped the Maya worldview.

Historical Context of Maya Spirituality

Maya spirituality was characterized by a polytheistic belief system, where gods and goddesses represented various aspects of the natural world and human existence. The Maya pantheon included deities associated with agriculture, fertility, rain, and even death. A notable aspect of Maya spirituality was the cyclical nature of time, as reflected in their calendar systems. The Maya used a combination of the Tzolk'in, a 260-day ritual calendar, and the Haab', a 365-day solar calendar, to mark significant events and rituals.

The Maya believed that every event in the universe was interconnected, and their rituals were designed to maintain balance and harmony between the terrestrial and celestial realms. This belief in interconnectedness extended to their ancestors, who were thought to play a vital role in the lives of the living. Ancestor veneration was a fundamental aspect of Maya spirituality, with the living seeking guidance and blessings from their forebears through various rituals and offerings.

Various archaeological findings, such as codices, pottery, and temple inscriptions, provide insight into the historical context of Maya rituals. For instance, the Dresden Codex, one of the few surviving pre-Columbian books, contains detailed information about rituals, astronomical events, and the agricultural calendar. These artifacts highlight the importance of rituals in maintaining agricultural cycles and honoring deities associated with fertility and harvests.

The Role of Rituals in Maya Society

Rituals in Maya society served multiple purposes, functioning as a means of communicating with the divine, reinforcing social hierarchies, and promoting community cohesion. They were often conducted by priests or shamans, who acted as intermediaries between the people and the gods. The rituals varied in complexity and significance, ranging from personal offerings to grand public ceremonies that involved the entire community.

One of the essential roles of rituals was to ensure agricultural success. The Maya were primarily agrarian, relying on maize, beans, and squash for sustenance. As a result, many rituals were centered around agricultural cycles, such as planting and harvest. These rituals often involved offerings to gods like Chaac, the rain god, and Yumil Kaxob, the maize god. The success of these offerings was believed to directly influence crop yields, making them a vital component of Maya society.

Additionally, rituals played a crucial role in reinforcing social hierarchies. The elite class, including rulers and priests, often held exclusive access to certain rituals, which helped maintain their power and status. Public ceremonies, such as those held during the New Year or during important life events, were opportunities for the elite to display their wealth and authority, further solidifying their position within the community.

Moreover, rituals served as an expression of cultural identity, allowing the Maya to connect with their heritage and maintain continuity in their traditions. Ceremonies were often accompanied by music, dance, and elaborate costumes, creating a vibrant tapestry of cultural expression that celebrated their beliefs and values.

In summary, the historical context of Maya spirituality and the role of rituals in society reveal a civilization that was deeply connected to its religious practices. These rituals were not merely religious acts; they were vital components of daily life, encompassing agricultural practices, social hierarchies, and cultural identity.

Key Aspects of Maya Rituals

The following are key aspects of Maya rituals that highlight their significance in the civilization:

- Polytheism: The belief in multiple gods representing various aspects of life.

- Cyclical Time: The understanding of time as a series of cycles, influencing agricultural practices.

- Ancestor Veneration: The practice of honoring ancestors through offerings and rituals.

- Community Participation: The collective involvement of the community in rituals, strengthening social bonds.

- Ritual Specialists: The role of priests and shamans as intermediaries between the divine and the people.

These aspects illustrate the multifaceted nature of Maya rituals and their integral role in the civilization's spiritual and social fabric.

Types of Offerings to the Gods

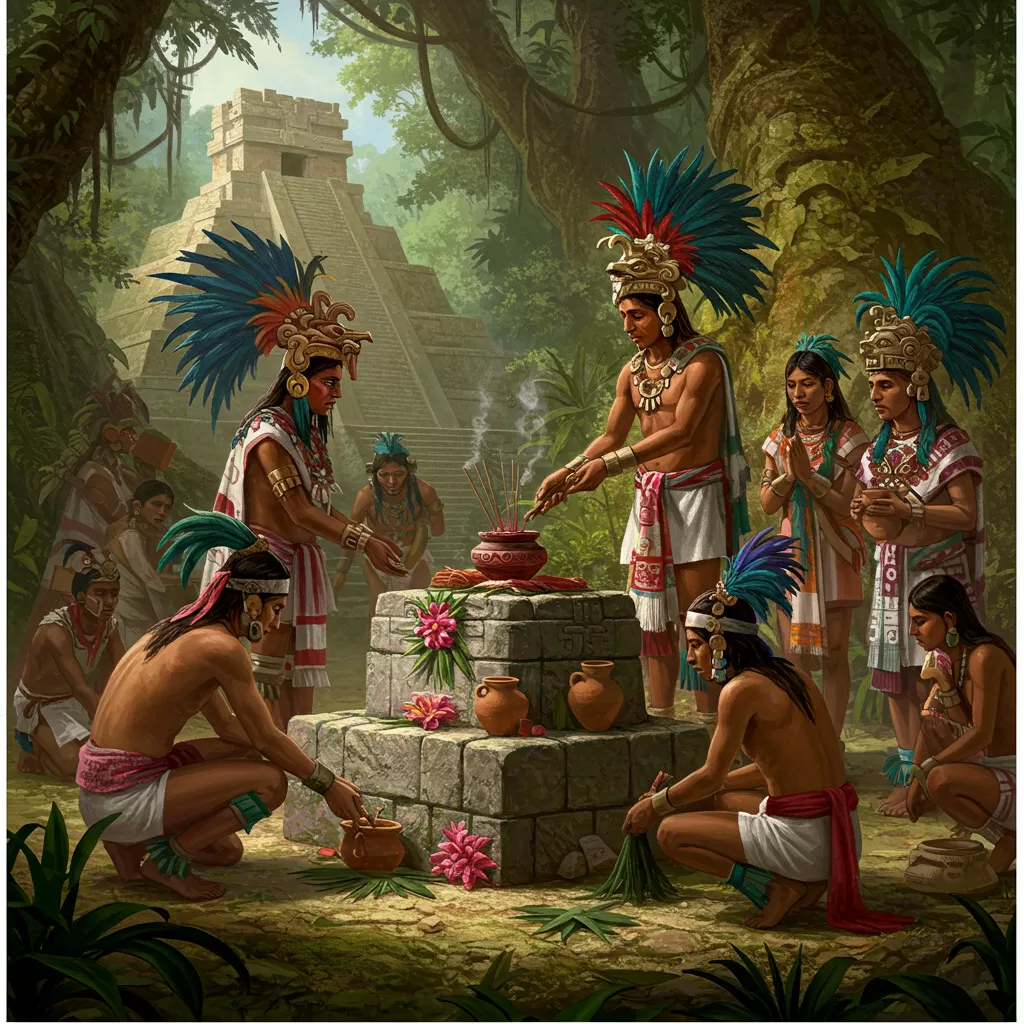

The Maya civilization, renowned for its rich cultural heritage and profound spiritual beliefs, placed great emphasis on the practice of rituals and offerings. These offerings served as a means to communicate with the divine, seek favor from the gods, and ensure balance in the natural world. Within this context, various types of offerings were made, each possessing unique significance and purpose. This section delves into the primary categories of offerings to the gods in Maya tradition: food and drink offerings, symbolic objects and altars, and animal sacrifices, exploring their meanings and the rituals surrounding them.

Food and Drink Offerings

Among the most common offerings to the gods were food and drink, which held great symbolic value. These offerings were not merely acts of devotion; they were essential components of Maya spirituality that reflected the interconnectedness between humans, nature, and the divine.

Food offerings typically included staple ingredients such as maize, beans, and squash, known collectively as the "Maya triad." Maize, in particular, was sacred and considered the "staff of life." The Maya believed that the gods had created humans from maize, thus offering it back to the deities was a way of honoring that creation. In addition to maize, the offerings might include fruits like cacao, which was revered not only for its flavor but also for its association with the gods. Cacao beans were often used as currency and played a pivotal role in rituals, signifying wealth and divine connection.

Drink offerings were equally important, with pulque (a fermented beverage made from the agave plant) and chocolate being among the most commonly offered liquids. Pulque was often associated with fertility and growth, while chocolate, especially when prepared as a frothy drink, was considered a divine elixir that could foster communion with the gods.

Rituals involving food and drink offerings were often elaborate, incorporating specific prayers, chants, and gestures. These rituals were conducted by priests or shamans, who acted as intermediaries between the people and the divine. The process typically involved the preparation of the offerings in a sacred space, often an altar, where they would be presented to the gods accompanied by incense, flowers, and other elements deemed holy.

Symbolic Objects and Altars

In addition to food and drink, the Maya utilized symbolic objects as offerings to the gods. These objects varied widely, encompassing pottery, textiles, and carved stone artifacts, each imbued with spiritual significance. The use of symbolic offerings was a manifestation of the Maya belief in animism, where objects were thought to possess spiritual essence.

Altars served as focal points for these offerings, often elaborately decorated and situated in sacred spaces such as temples or ceremonial centers. The construction and adornment of altars were rituals in themselves, involving careful selection of materials and items to reflect the specific intent of the offering. For example, a fertility altar might include figurines representing deities associated with crops and reproduction, while an altar dedicated to death would feature items that honored ancestors.

One prominent example of symbolic offerings is the use of jade and obsidian. Jade held immense value in Maya culture, symbolizing life and fertility. It was often fashioned into amulets or pendants and offered to the gods during significant ceremonies. Obsidian, on the other hand, was associated with warfare and the underworld, often used in the creation of tools and weapons. Offering obsidian to the gods was a way to seek protection and favor in matters of conflict.

Textiles, such as woven cloth dyed with natural pigments, were also significant offerings. These textiles often featured intricate patterns and designs that conveyed cultural meaning and were believed to carry the prayers and intentions of the maker. By presenting these textiles to the gods, the Maya sought to share their creativity and devotion.

Animal Sacrifices and Their Significance

Animal sacrifices were perhaps the most dramatic and significant type of offerings in Maya rituals. These acts were deeply rooted in the belief that blood and life force could appease the gods and ensure balance within the universe. The Maya viewed blood as a vital substance that connected the human and divine realms, making it a powerful medium for offerings.

Commonly sacrificed animals included birds, such as turkeys and chickens, as well as larger animals like deer and jaguars. The choice of animal often depended on the specific deity being honored and the nature of the ritual. For example, a jaguar, revered for its strength and connection to the underworld, might be sacrificed during a ritual seeking protection or power.

The process of animal sacrifice was highly ritualized, involving specific prayers and ceremonies performed by priests. The act of sacrifice was not merely an act of violence; it was framed within a context of reverence and respect for the life being taken. The Maya believed that the spirit of the sacrificed animal would ascend to the gods, carrying with it the intentions and supplications of the community.

After the sacrifice, the animal's remains were often used in various ways, including communal feasts that brought people together in celebration and gratitude. The consumption of the sacrificial animal further solidified the connection between the community and the divine, reinforcing the idea that offerings were not solely for the gods, but also for the benefit of the people.

Animal sacrifices were often accompanied by other offerings such as food, drink, and symbolic objects. This multi-faceted approach to offerings reflected the Maya understanding of the complex and interwoven nature of life, death, and spirituality.

Ritual Contexts for Offerings

The Maya calendar played a crucial role in determining the timing and nature of offerings. Certain days were considered especially auspicious for specific rituals, and the Maya meticulously observed celestial events, agricultural cycles, and seasonal changes to align their offerings with the rhythms of the universe.

For instance, during the planting season, rituals would be conducted to honor the earth and seek the blessings of the maize god. Offerings of food and symbolic objects would be made to ensure a prosperous harvest. Similarly, during the time of the new year, elaborate ceremonies would be held to mark the transition and seek favor from the gods for the year ahead.

Communal participation in these rituals was essential, as the Maya believed that collective offerings amplified their power and efficacy. Festivals, which often incorporated music, dance, and theatrical performances, served as a means to engage the community in shared spirituality, reinforcing social cohesion and cultural identity.

The integration of offerings into daily life was a hallmark of Maya spirituality, where the sacred and the mundane coexisted. Offerings were not confined to grand ceremonies but permeated everyday practices, from household altars to personal rituals. This constant engagement with the divine underscored the Maya worldview, where every action had spiritual significance.

In conclusion, the types of offerings to the gods in Maya culture were diverse and multifaceted, encompassing food and drink, symbolic objects, and animal sacrifices. Each offering was steeped in meaning, reflecting the intricate relationship between the Maya people, their environment, and the divine. These practices not only served to honor the gods but also fostered community identity, continuity, and a profound sense of belonging within the cosmos.

Significant Maya Ceremonies

The Maya civilization, known for its profound understanding of astronomy, mathematics, and architecture, also had a rich tapestry of rituals and ceremonies that were integral to their cultural and spiritual identity. These ceremonies served not only as religious observances but also as communal gatherings that reinforced social structures and cultural continuity. Among the myriad of ceremonies observed by the Maya, three stand out for their historical significance and cultural relevance: the celebration of the Maya New Year, rituals for fertility and agriculture, and ceremonies honoring death and ancestor worship.

The Maya New Year Celebration

The Maya New Year, or Wíik'ib' K'iik', marks the beginning of a new cycle in the Maya calendar, which is intricately linked to their agricultural practices and cosmological beliefs. Celebrated around the time of the spring equinox, this event symbolizes renewal, rebirth, and the reawakening of the earth. The Maya believed that the new year was a period of great significance, as it was thought to affect agricultural productivity and the well-being of the community.

Preparations for the New Year celebration would begin well in advance, involving rituals to cleanse the community and appease the gods. A key component of these preparations included the making of offerings, which could range from food items to symbolic objects that held spiritual significance. These offerings were often placed on altars adorned with flowers, feathers, and incense, creating a vibrant and sacred space for the ceremonies.

During the celebration itself, the Maya would engage in various activities, including feasting, dancing, and ritual performances. One of the most important aspects of the New Year ceremony was the ceremonial ball game, known as pok-a-tok, which held deep religious and social implications. The outcome of the game was believed to influence the favor of the gods, impacting agricultural yields for the coming year.

In many communities, the New Year celebration would feature a grand procession where priests and community leaders would invoke the gods through chants and music, asking for blessings on crops and livestock. This public display of devotion served to unite the community and reaffirm their shared beliefs and cultural identity.

Rituals for Fertility and Agriculture

Fertility and agriculture were central to the Maya way of life, deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs. The Maya understood that their survival depended on the cycles of nature, and as such, they developed rituals to honor the gods responsible for these cycles. These rituals were particularly focused on the agricultural calendar, with specific ceremonies aligned to sowing and harvest times.

One prominent ritual associated with fertility is the Chak ceremony, dedicated to the rain god who was believed to be crucial for crop growth. During this ceremony, community members would gather at sacred sites, often near water sources, to conduct offerings that included food, flowers, and incense. The priests would perform rituals to invoke the rain god's blessings, ensuring adequate rainfall for the crops. Additionally, the Maya would often use symbolic objects, such as maize and other crops, as offerings, reflecting their deep connection to the earth.

Another significant aspect of agricultural rituals was the use of divination to determine the most auspicious times for planting and harvesting. This involved consulting with priests or shamans who interpreted the movements of the stars and other natural phenomena. The rituals often included music, dance, and the sharing of traditional foods, creating a festive atmosphere that celebrated the community's relationship with the land.

To further enhance fertility, the Maya also performed rituals that involved the symbolic planting of seeds in sacred spaces, often accompanied by prayers and chants. These acts were intended to ensure not only the fertility of the land but also the fertility of the people, linking agricultural success to the overall prosperity of the community.

Death and Ancestor Worship Ceremonies

Death and the reverence for ancestors played a crucial role in Maya spirituality, reflecting their belief in the cyclical nature of life. The Maya viewed death not as an end, but as a transition to another realm, where ancestors continued to influence the living. This understanding led to elaborate ceremonies to honor the deceased and maintain a connection with past generations.

One of the most significant ceremonies related to death was the Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. This celebration, which has its roots in ancient Maya customs, emphasizes the importance of remembering and honoring deceased loved ones. Families would create altars in their homes and cemeteries, adorned with photographs, favorite foods, and offerings to invite the spirits of the deceased to join the living in celebration. The altars often featured items like pan de muerto, a special bread, and marigold flowers, which are believed to guide the spirits back to the world of the living.

In addition to the Day of the Dead, the Maya performed various rituals throughout the year to honor their ancestors. These rituals often involved feasting, music, and offerings made at ancestral burial sites. The act of sharing food with the deceased was seen as a way to reinforce familial bonds and ensure the ancestors' continued support and guidance.

Another important aspect of ancestor worship involved the use of funerary rites, which varied depending on the status of the individual and their role in society. High-ranking individuals, such as kings and nobles, were often buried with elaborate grave goods, including pottery, jewelry, and food offerings, reflecting their importance and the belief that they would continue to exert influence in the afterlife. Common people, while buried with less grandeur, still received rituals that honored their contributions to the community.

The Maya also believed in the concept of nahual, where each person had a spirit animal or guardian that guided them throughout their lives. Rituals to honor these spirit guides were often intertwined with ancestor worship, emphasizing the interconnectedness of life and death in Maya belief systems.

Key Elements of Maya Ceremonies

The ceremonies of the Maya civilization were characterized by various elements that underscored their cultural significance. These elements included:

- Offerings: Food, flowers, and symbolic objects were commonly used to appease the gods and honor ancestors.

- Music and Dance: Integral to many ceremonies, music and dance served to invoke the divine and foster community spirit.

- Ritual Objects: Items such as incense, ceremonial masks, and altars were central to the rituals, embodying the connection between the physical and spiritual worlds.

- Community Participation: Ceremonies often involved the entire community, reinforcing social bonds and shared beliefs.

- Divination: Consulting with priests or shamans was common to determine auspicious times for rituals, reflecting the Maya's deep understanding of natural cycles.

The rich tapestry of Maya ceremonies reflects a civilization deeply in tune with the rhythms of nature and the spiritual realms. These rituals not only served to honor the gods and ancestors but also reinforced the cultural identity of the Maya people, ensuring the continuity of their beliefs and practices through generations.