Aztec Society: Nobles, Commoners, and Slaves

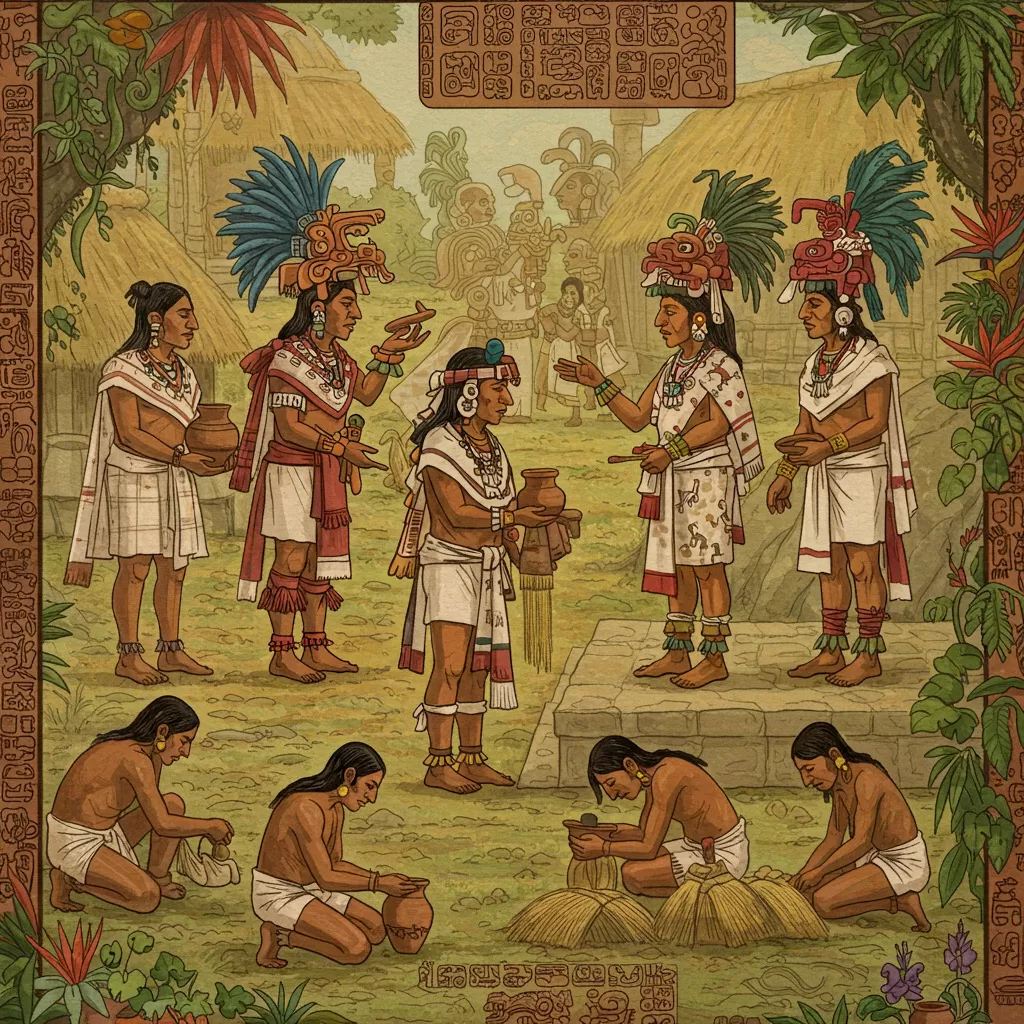

The Aztec Empire, one of the most remarkable civilizations in pre-Columbian America, boasted a complex social structure that played a pivotal role in its development and functioning. Understanding the dynamics of Aztec society provides valuable insight into how the empire sustained itself through a well-defined hierarchy composed of nobles, commoners, and slaves. Each group had distinct roles, responsibilities, and social standings that contributed to the overall stability and prosperity of the civilization.

The nobility held significant power and influence, shaping political decisions and religious practices, while commoners formed the backbone of daily life through their various occupations and community engagements. Meanwhile, the existence of slavery added another layer of complexity, highlighting issues of economic necessity and social stratification. By exploring these facets of Aztec society, we can appreciate how interwoven relationships among these classes fostered a unique cultural identity that thrived amidst challenges.

Structure of Aztec Society

The Aztec Empire, which thrived from the 14th to the 16th century in what is now Mexico, exhibited a complex social structure that was deeply intertwined with its religious beliefs, economic practices, and military conquests. Understanding the structure of Aztec society is crucial to grasping how the Aztecs governed, interacted with one another, and maintained their vast empire. This section explores the social hierarchy, the role of religion, and the influence of warfare on the social structure of the Aztec civilization.

Overview of Social Hierarchy

At the apex of the Aztec social hierarchy were the nobles, known as the pilli, who were often born into their status and held significant power. This elite class included high-ranking officials, military leaders, and priests, all of whom played critical roles in governance and religious practices. Below the nobles were the commoners, or macehualtin, who made up the majority of the population. They were engaged in various occupations, including farming, trade, and crafts, serving as the backbone of the economy.

At the base of the hierarchy were the slaves, or tlacotin, who had a very different status compared to the nobles and commoners. Slavery in Aztec society was not merely a result of conquest; it also stemmed from debt and criminal punishment. The status of slaves was unique, as they could own property, marry free individuals, and even buy their freedom under certain circumstances. This nuanced view of slavery in Aztec culture demonstrates the complexity of their social structure.

This hierarchical structure was not rigid; social mobility was possible, particularly through military achievement or acquiring wealth. A commoner could rise to a noble status by demonstrating valor in battle or by amassing wealth through trade. The dynamic nature of the social hierarchy was a reflection of the Aztecs' values, emphasizing merit and contribution to society over mere birthright.

Role of Religion in Society

Religion was a central pillar of Aztec life that shaped every aspect of their society. The Aztecs were polytheistic, worshiping a pantheon of gods, each representing different elements of nature and human experience. The most significant deity was Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, whose worship was intimately tied to the Aztecs' militaristic culture.

The clergy, comprised mainly of nobles, held significant power and influence. They were responsible for conducting rituals, including human sacrifices, which were believed to sustain the gods and ensure the continuation of the world. The religious calendar was filled with festivals and ceremonies, reinforcing social cohesion and hierarchy. For instance, during major religious events, nobles would showcase their wealth and power, while commoners would participate in the rituals, strengthening their ties to the ruling class.

Moreover, the temples and religious sites were often built in the heart of cities, symbolizing the centrality of religion within Aztec society. These structures not only served as places of worship but also functioned as centers of education and governance. The intertwining of religion and state affairs underscored the idea that the wellbeing of the empire was directly linked to the favor of the gods. This belief system provided a justification for the social hierarchy, as the nobles, as intermediaries between the gods and people, were seen as essential to maintaining cosmic order.

Influence of Warfare on Social Structure

Warfare played a crucial role in shaping the Aztec social structure. The Aztecs were a militaristic society, and their conquests expanded their territory and resources. Victorious warriors gained prestige and, often, a higher social status. Military achievements were celebrated and rewarded with titles, land, and wealth, which could elevate a commoner to noble status. This meritocratic aspect of the military was vital for maintaining loyalty and encouraging participation in campaigns.

Furthermore, warfare provided the Aztecs with captives for their religious rituals. The need for sacrificial victims to appease the gods further incentivized military conquests. Captured warriors were often honored for their bravery in battle, even as they faced sacrificial death. This paradox highlighted the complex relationship between warfare, religion, and social structure, where acts of violence were both a source of power and a means of sustaining the societal order.

In conclusion, the structure of Aztec society was a tapestry woven from the threads of hierarchy, religion, and warfare. Understanding this complex interplay provides insights into how the Aztecs functioned as a civilization and how they maintained their empire over centuries. The social hierarchy was characterized by a dynamic relationship between the nobles, commoners, and slaves, reflecting a society that valued both birth and merit. Religion provided the ideological framework that justified this hierarchy, while warfare facilitated social mobility and reinforced the power of the elite.

The Nobility of the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, renowned for its rich cultural heritage, sophisticated societal structure, and formidable military prowess, was heavily stratified, with a distinct class of nobility at its helm. The nobles, or pipiltin, played a pivotal role in the governance, economy, and religious practices of Aztec society. In this section, we will explore the definition and importance of nobles, their roles and responsibilities, as well as some prominent noble families and leaders who shaped the course of Aztec history.

Definition and Importance of Nobles

In the context of the Aztec Empire, the term pipiltin refers to the noble class, which encompassed individuals of high social status, often distinguished by their lineage, wealth, and education. Nobles were typically born into their status, inheriting not only property but also political power and religious authority. They were essential in maintaining the social order and executing the laws within the empire, serving as key figures in both the administration and the military.

The nobility's significance cannot be overstated. They served as the ruling elite, advising the emperor and holding various government positions. Nobles were responsible for land management, tax collection, and local governance, ensuring the efficient functioning of the empire's vast territories. Additionally, they played a crucial role in religious life, conducting ceremonies and rituals that reinforced the societal hierarchy and the divine right of the rulers.

Roles and Responsibilities of Nobles

The nobles of the Aztec Empire were entrusted with numerous roles and responsibilities that extended across various domains, including governance, military, and religion. Their multifaceted duties were essential for the stability and prosperity of the empire.

- Governance: Nobles held significant political power, often serving as governors of provinces. They were responsible for enforcing laws, collecting tribute, and administering justice. Their authority allowed them to maintain local order and manage resources effectively.

- Military Leadership: Many nobles were also military leaders, commanding troops during warfare. Their noble status often afforded them access to elite training and resources, making them skilled warriors. They played a crucial role in expanding the empire's territory through conquests, which further enhanced their power and prestige.

- Religious Duties: Nobles participated actively in religious ceremonies, acting as intermediaries between the gods and the people. They were responsible for conducting sacrifices, rituals, and festivals, which were integral to Aztec spirituality and the community's well-being. Their involvement in religion reinforced their authority and the societal hierarchy.

- Education: Nobles received formal education, allowing them to become literate and knowledgeable in various subjects, including history, law, and astronomy. This education enabled them to make informed decisions and contributed to their roles in governance and religious practices.

Prominent Noble Families and Leaders

The Aztec Empire boasted several prominent noble families and leaders whose influence shaped its history. Among these, the most notable include:

| Noble Family | Notable Figures | Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| House of Moctezuma | Moctezuma II | Emperor during the Spanish conquest; known for his complex governance and diplomacy. |

| House of Axayacatl | Axayacatl | Expanded the empire; known for military campaigns against neighboring states. |

| House of Itzcali | Cuauhtémoc | Last emperor of the Aztecs; led resistance against Spanish conquest. |

The House of Moctezuma, for instance, produced several emperors, including Moctezuma II, who ruled during a crucial period when the Aztec Empire was at its zenith. His reign was marked by extensive diplomatic relationships and an intricate tribute system that connected various city-states. Moctezuma II’s encounter with the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés is a pivotal moment in history, illustrating the complexities of power dynamics and cultural exchanges.

Another influential figure was Axayacatl, known for his military prowess and expansionist policies. Under his leadership, the Aztec Empire undertook significant territorial conquests, bringing more city-states under its control. His reign laid the groundwork for the imperial structure that characterized the Aztec political landscape.

Cuauhtémoc, the last emperor of the Aztecs, epitomizes the resistance against Spanish colonization. After Moctezuma II's death, Cuauhtémoc emerged as a symbol of bravery and resilience, leading the defense of the empire against overwhelming odds. His legacy is celebrated in Mexican history as a testament to the struggle for sovereignty and identity.

In conclusion, the nobility of the Aztec Empire was a complex and integral component of its societal structure. The roles and responsibilities of the nobles, along with the influence of prominent families and leaders, shaped the political, military, and religious landscape of the time. Understanding the importance of the noble class provides insight into the mechanisms of power and governance that characterized the Aztec civilization, a society that continues to influence modern Mexico.

Commoners and Their Daily Lives

The Aztec Empire, flourishing from the 14th to the 16th centuries, was marked by a complex social structure that included a defined hierarchy of nobles, commoners, and slaves. Among these groups, commoners played a vital role in ensuring the empire's economy and social stability. This section delves into the lives of commoners, exploring their social status, occupations, family structures, and community life.

Social Status of Commoners

In the Aztec social hierarchy, commoners were situated below the nobles but above slaves. This position granted them a certain degree of respect and autonomy within society, although their lives were often governed by the obligations and expectations set forth by the ruling classes. Commoners were typically categorized into two main groups: pochteca and tlacotin.

The pochteca were the merchant class, who not only engaged in trade but also acted as diplomats and spies for the empire. Their role was crucial in expanding the Aztec economy and establishing trade networks across Mesoamerica. The tlacotin, on the other hand, were agricultural workers, artisans, and laborers who contributed directly to the sustenance and production of goods necessary for daily life.

While commoners did not enjoy the privileges of the noble class, they were essential to the functioning of Aztec society. Their contributions were recognized, and some commoners could even rise to prominence through successful trade or skilled craftsmanship, potentially gaining access to higher social circles.

Occupations and Economic Activities

The daily lives of commoners were primarily centered around their occupations, which varied widely based on location and available resources. Agriculture was the backbone of the Aztec economy, with the majority of commoners engaged in farming. The Aztecs utilized innovative agricultural techniques, such as chinampas—floating gardens built on lakes—to maximize crop yields. Common crops included maize, beans, squash, and chilies, which formed the staple diet of the population.

Aside from agriculture, commoners also participated in various trades and crafts. Skilled artisans created pottery, textiles, and jewelry, which were highly valued in Aztec society. The market system played a significant role in the daily life of commoners, with local markets serving as hubs for trade and social interaction. Goods were exchanged through a barter system, and the markets were often bustling with activity, reflecting the vibrant economy of the Aztec Empire.

Moreover, commoners were involved in construction projects, such as building temples, roads, and other public works, often under the direction of noble overseers. This not only provided labor for necessary infrastructure but also reinforced the social order, as commoners were seen as fulfilling their duties to the state and the gods.

Family Structure and Community Life

The family unit was fundamental to the lives of commoners in the Aztec Empire. Families typically consisted of extended members living together, including parents, children, grandparents, and other relatives. This structure facilitated mutual support in agricultural practices and household duties. Gender roles were distinct; men primarily engaged in farming, trade, and warfare, while women were tasked with managing the household, raising children, and participating in weaving and cooking.

A significant aspect of community life was the emphasis on communal activities and celebrations. Festivals played a crucial role in strengthening social bonds among commoners. These events often revolved around agricultural cycles, honoring deities and celebrating harvests. The most notable of these was the Tlacaxipehualiztli, which celebrated the renewal of life and the agricultural bounty, integrating rituals that emphasized the connection between the people and their gods.

Education was also an essential feature of common life among the commoners. While formal education was primarily reserved for nobles, commoners did receive practical instruction from their parents and elders. Children learned agricultural techniques, crafts, and the cultural traditions of their people, ensuring the transmission of knowledge across generations.

The community was further strengthened by the calpulli, a form of clan or kinship group that provided social, economic, and political support. Members of a calpulli shared land, resources, and responsibilities, fostering a sense of belonging and mutual aid. Decisions within the calpulli were made collectively, allowing commoners to have a voice in local governance, albeit limited compared to the nobility.

Religion and Its Influence on Commoners

Religion permeated every aspect of daily life for commoners in the Aztec Empire. The belief in a pantheon of gods and goddesses influenced agricultural practices, community activities, and personal rituals. Commoners participated in regular religious observances, which reinforced their social identity and connection to the larger Aztec civilization.

Rituals often included offerings to deities in the form of food, flowers, and sometimes human sacrifices, which were believed to appease the gods and ensure the continuation of the world. Commoners were expected to participate in these practices, further solidifying the notion that their everyday lives were intertwined with the divine will.

Temples and shrines were central to community life, serving as places not only for worship but also for gathering and socializing. Festivals and rituals marked significant events in the agricultural calendar, allowing commoners to come together in celebration and reaffirmation of their cultural identity.

Challenges Faced by Commoners

Despite their integral role in Aztec society, commoners faced numerous challenges. The demands of tribute to the empire could be burdensome, often requiring them to give a portion of their harvest or labor to the ruling class. This tribute system created a complex relationship between commoners and nobles, where the latter were seen as both protectors and oppressors.

Additionally, commoners were subject to the whims of the natural environment, which could lead to food shortages and economic strain. Droughts or flooding could devastate crops, causing hardship for families and communities reliant on agriculture. In such instances, community solidarity often became crucial for survival, with families pooling resources to support one another during difficult times.

Furthermore, commoners were frequently caught in the conflicts and wars waged by the empire. While noble warriors were celebrated for their bravery, commoners were often conscripted into military service, risking their lives for the expansion of Aztec territory. This could lead to loss of life and disruption of families, further complicating their existence within the empire.

Conclusion

Commoners in the Aztec Empire led lives that were both rich and challenging, marked by their critical contributions to agriculture, trade, and community life. Their roles, while often overshadowed by the nobility, were essential for the sustenance and stability of the empire. Understanding the daily lives of commoners provides valuable insight into the complexities of Aztec society and the interdependence of its various social classes. The resilience and adaptability of commoners played a significant role in the enduring legacy of the Aztec civilization, leaving behind a rich cultural heritage that continues to be studied and appreciated today.

The Role of Slaves in Aztec Society

Slavery in the Aztec Empire was an integral component of the societal structure, playing a multifaceted role that influenced various aspects of daily life, economy, and even warfare. To understand the dynamics of slavery during this period, it is essential to explore the definition and types of slavery, the sources of slavery and the conditions of life for slaves, as well as the rights and duties they held within this complex social hierarchy.

Definition and Types of Slavery

In the context of the Aztec Empire, slavery was not merely a matter of servitude; it was a recognized institution with specific definitions and categorizations. Slaves, or "tlacotin," were individuals who were owned by others and were compelled to work without remuneration. However, this definition encompasses a variety of situations and conditions under which individuals could become slaves.

- Debt Slavery: Many individuals fell into slavery due to debts. If a person could not repay a loan, they could sell themselves or a family member into slavery to settle the debt.

- War Captives: One of the primary sources of slavery was the capture of individuals during warfare. Enemies defeated in battle were often enslaved and brought back to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, where they were integrated into the slave population.

- Criminal Punishment: Certain crimes could lead to an individual being sentenced to slavery. This form of punishment was often reserved for serious offenses that warranted a loss of freedom.

These different types of slavery illustrate that not all slaves were in the same condition; some could expect to eventually regain their freedom, especially in cases of debt or war captives. This nuanced understanding of slavery in the Aztec Empire contrasts sharply with the more rigid forms of slavery seen in other cultures, such as the antebellum American South.

Sources of Slavery and Conditions of Life

The sources of slavery in the Aztec Empire highlight the complex social and economic interactions prevalent during this era. The Aztecs often engaged in warfare not only for territorial expansion but also to acquire prisoners who could be enslaved. The motivations for this practice were both economic and religious, as these captives could provide labor and were also viewed as potential sacrifices to the gods.

Life as a slave in Aztec society varied significantly depending on their origins and the circumstances surrounding their enslavement. While some slaves endured harsh conditions and laborious tasks, others could experience a relatively privileged existence.

| Condition | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Harsh Labor | Engaged in physically demanding tasks, often in agriculture or construction. | Farming, building temples. |

| Domestic Slaves | Worked within households, often treated with more leniency. | Cooking, cleaning, childcare. |

| Specialized Roles | Some slaves held specialized skills and could attain a higher status. | Artisans, scribes. |

Overall, while many slaves faced challenging conditions, their experiences were not uniform. Domestic slaves could enjoy a more favorable status, often integrating into the family unit of their masters, while agricultural and labor slaves typically endured harsher conditions. Additionally, some slaves had the opportunity to earn their freedom through various means, including financial compensation or by fulfilling specific obligations.

Rights and Duties of Slaves

Despite their status, slaves in Aztec society had certain rights and responsibilities that set them apart from the more absolute forms of slavery seen in other civilizations. These rights were crucial in understanding the broader dynamics of Aztec society.

- Legal Rights: Slaves could own property, including other slaves. They were afforded some legal protections, allowing them to seek redress for abuse or mistreatment.

- Ability to Buy Freedom: Slaves could work to earn money to buy their freedom or could be freed by their masters under certain conditions.

- Familial Relationships: Many slaves maintained familial ties, which were respected within the Aztec legal framework. A slave could marry and have children, with their offspring often not inheriting their enslaved status.

On the flip side, slaves also had specific duties and obligations to their owners. They were expected to perform tasks assigned by their masters, which could range from labor-intensive work to domestic chores. Additionally, slaves could be called upon to participate in religious rituals, especially those involving human sacrifices, which were a critical aspect of Aztec religious life.

In conclusion, the role of slaves in Aztec society was complex and multifaceted. Slavery was not merely a system of oppression; it was embedded within a broader social and economic framework that allowed for various forms of agency among slaves. Understanding the nuances of slavery in the Aztec Empire provides valuable insights into the workings of this ancient civilization and its social structures.