Aztec Society: A Complex Hierarchy of Power

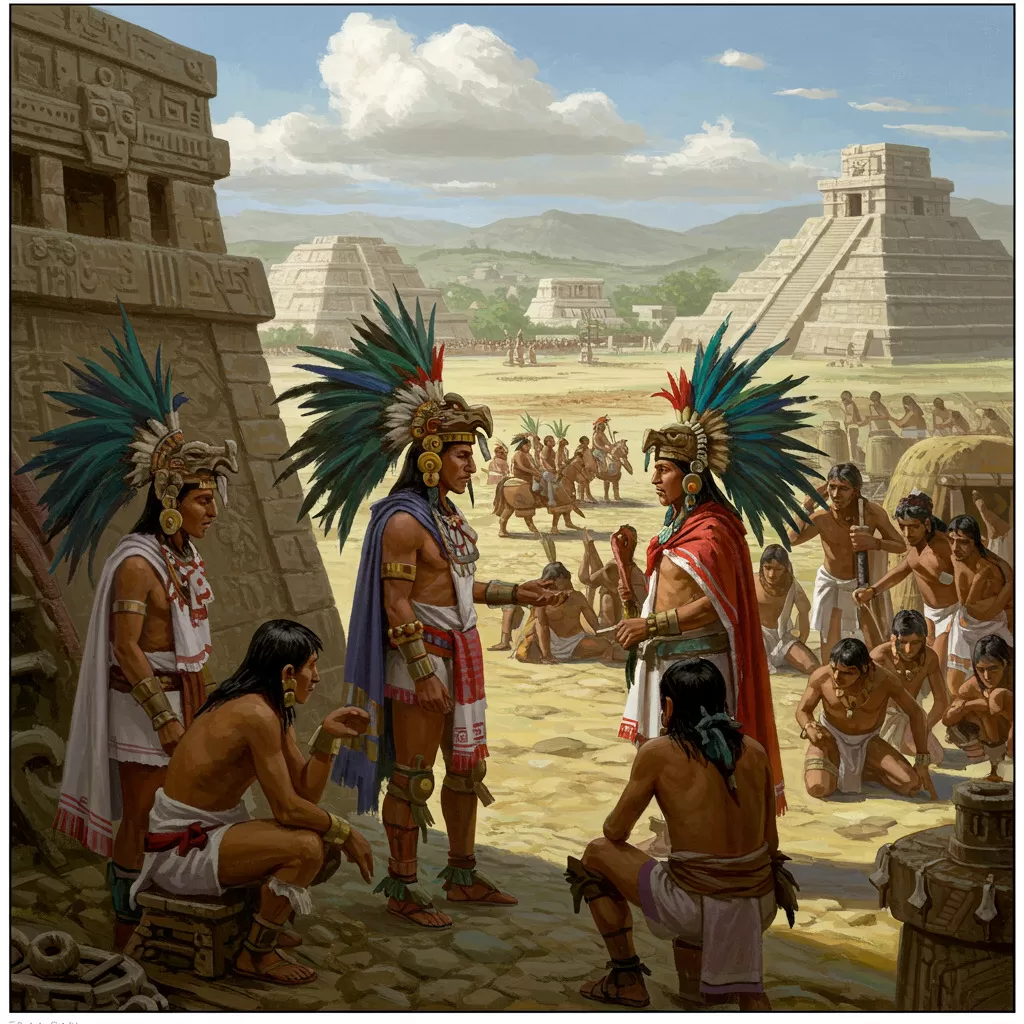

The Aztec civilization, renowned for its rich culture and advanced societal structures, flourished in Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. At the heart of this vibrant society was a complex hierarchy that dictated the roles and relationships among its people. Understanding the intricacies of Aztec society reveals not only their remarkable achievements in governance and economy but also the profound influence of class divisions on daily life and cultural practices.

The Aztec social structure was meticulously organized, encompassing various classes, including the nobility, priests, commoners, and even slaves. Each group played a distinct role in the functioning of the empire, contributing to its stability and growth. This article delves into the multifaceted layers of Aztec society, exploring the power dynamics, economic systems, and the political organization that characterized one of the most fascinating civilizations in history.

Structure of Aztec Society

The Aztec civilization, flourishing in central Mexico from the 14th to the 16th centuries, was characterized by a complex social hierarchy that played a crucial role in its political, economic, and cultural life. Understanding the structure of Aztec society is essential to appreciate the interplay of power, religion, and daily life within this ancient civilization. The society was broadly divided into four main categories: the nobility, the priesthood, commoners, and slaves. Each of these groups had distinct roles, responsibilities, and influences, creating a multifaceted system that governed the lives of millions.

The Nobility: Roles and Influence

The Aztec nobility, known as the pipiltin, held significant power and influence within the societal framework. This class was composed of individuals who were often related to the ruling families or had distinguished themselves through military prowess or wealth. Nobles were crucial in the administration of the city-states, known as altepetl, serving as governors, military leaders, and advisors to the emperor.

Members of the nobility enjoyed various privileges, including access to education, land ownership, and exemption from certain taxes. They often lived in large, ornate houses and participated in elaborate ceremonies that showcased their status. The noble class was responsible for maintaining order and enforcing laws, which were strictly adhered to by the commoners. Their roles extended beyond governance; they were also patrons of the arts and religion, commissioning works that glorified the Aztec gods and their own lineage.

Within the noble class, there were different ranks, with the highest being the tlatoani, the king or emperor, who wielded ultimate authority over the empire. The tlatoani was seen as divinely appointed, embodying both political and spiritual leadership. This reverence placed the nobility in a unique position; while they were powerful, they were also expected to uphold the moral and religious standards of society.

The nobility's influence extended into warfare, as they were often the commanders of military campaigns. Their role as warriors not only served to expand the empire but also to enhance their prestige and power. Victories in battle brought wealth and captured prisoners, who were often used for sacrificial rituals, further intertwining warfare with religious practices.

The Priesthood: Religion and Power

Religion was an integral aspect of Aztec society, and the priesthood held a sacred position within the social hierarchy. The priests, known as tlatlacotin, played a vital role in maintaining the religious practices that were essential to appease the gods and ensure the prosperity of the Aztec civilization. The Aztecs believed in a pantheon of gods, each representing different elements of life, such as agriculture, war, and fertility. Festivals and rituals were conducted to honor these deities, and the priests were the mediators between the gods and the people.

The priesthood was organized into various levels, with the high priests having the most significant influence. They were responsible for conducting major ceremonies, including human sacrifices, which were believed to be necessary to sustain the gods and, in turn, the world. The high priests were often members of the noble class, ensuring that they not only held spiritual power but also political sway.

Training to become a priest was rigorous, requiring years of study in the codices, which contained religious texts and rituals. The priests were well-versed in astronomy, mathematics, and medicine, making them some of the most educated individuals in Aztec society. Their knowledge allowed them to play a crucial role in agricultural cycles, as they interpreted celestial movements to determine the best times for planting and harvesting.

Despite their elevated status, the priests were also subject to the same societal expectations as the nobility. They were required to live austere lives and dedicate themselves to the service of the gods and the community. Their power was not absolute; they often collaborated with the nobility to ensure that their religious practices aligned with the political objectives of the empire.

Commoners: Daily Life and Duties

The commoners, or macehualtin, comprised the majority of Aztec society and played a crucial role in the economy and daily functioning of the empire. This class included farmers, artisans, traders, and laborers. While they did not hold the same privileges as the nobility, their labor was essential for sustaining the population and the elite.

Most commoners were engaged in agriculture, cultivating crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which formed the backbone of the Aztec diet. They employed advanced farming techniques, including the use of chinampas, or floating gardens, which allowed them to maximize agricultural output. The Aztecs also practiced crop rotation and irrigation, showcasing their innovative approaches to farming.

Artisans and traders contributed to the economy through the production of goods and commerce. Artisans crafted pottery, textiles, and jewelry, which were highly valued in both local and regional markets. Trade was facilitated through a network of marketplaces, with the Tlatelolco market being one of the largest and most vibrant in the empire. Commoners participated in trade, exchanging their goods for products from other regions, thus contributing to a dynamic economic system.

Social mobility was limited for commoners, but it was possible for individuals to rise in status through military achievements or by gaining wealth as successful traders or artisans. However, the daily lives of most commoners were dictated by their labor and obligations to the state, including tribute payments to the nobility.

Family units were central to commoner life, with extended families often living together and sharing responsibilities. Women played a vital role in both the household and the economy, managing domestic chores and contributing to agricultural production. Their contributions, although often overlooked, were fundamental to the survival and stability of Aztec society.

Slavery in Aztec Culture

Slavery in Aztec culture, while present, was markedly different from the chattel slavery seen in later periods. The Aztecs had a system of slavery that stemmed from various sources, including warfare, debt, and punishment for crimes. Slaves, known as tlacotin, were often captured during military campaigns and used for labor, household duties, or sacrifices. However, they had certain rights and could own property, marry free individuals, and eventually purchase their freedom.

Slavery was not a permanent state for many; for instance, individuals who fell into debt could sell themselves into slavery temporarily to pay off obligations. This system allowed for a level of social mobility, as some slaves could work their way back into freedom through their labor. It is important to note that slaves were considered a part of society and had roles, albeit limited, within the social hierarchy.

While slavery was a means to fulfill economic needs, the treatment of slaves varied. Those held in households were often treated better than those used for hard labor or sacrifices. Nonetheless, the threat of sacrifice loomed large in Aztec culture, as captured warriors were often seen as valuable offerings to the gods.

The practice of slavery in Aztec society underscores the complex interrelations of power, economy, and religion. It reveals how the Aztecs constructed their social order, balancing the needs of the elite with the contributions of the lower classes.

In conclusion, the structure of Aztec society was a sophisticated and intricate hierarchy that defined the relationships between the nobility, priesthood, commoners, and slaves. Each group played a vital role in maintaining the stability and prosperity of the civilization, highlighting the interconnectedness of social, political, and economic factors in the Aztec world. This hierarchical structure not only facilitated governance and order but also underscored the importance of religion and cultural practices in shaping the lives of the Aztecs.

Political Organization and Governance

The political organization and governance of the Aztec Empire were complex and multifaceted, reflecting a sophisticated system that combined elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and local governance. This system was essential for managing the vast territories and diverse populations that fell under Aztec control. The political structure not only facilitated the administration of the empire but also reinforced the social hierarchy that permeated Aztec society.

The Role of the Emperor

At the pinnacle of Aztec political organization was the emperor, known as the tlatoani. The emperor was not just a political leader but also a figure of religious significance, believed to be the representative of the gods on Earth. His authority was derived from a combination of divine right and military prowess. The emperor was responsible for maintaining order, overseeing the welfare of the people, and leading military campaigns. His legitimacy was further reinforced through rituals and ceremonies that underscored his connection to the divine.

The position of the tlatoani was often hereditary, typically passed down within noble families. However, it was not uncommon for the nobility to choose a new emperor based on merit, particularly if a candidate demonstrated exceptional leadership or military skills. This practice ensured that the most capable individuals could ascend to power, maintaining a level of competency in governance.

The emperor's court was a hub of political activity, where advisors, nobles, and military leaders gathered to discuss matters of state. The emperor relied on this council for support in decision-making, especially regarding military campaigns and diplomatic relations. Despite the emperor's supreme authority, he often sought consensus among his advisors, reflecting a governance style that valued input and cooperation.

Regional Leaders and City-States

The Aztec Empire was not a monolithic entity; it was composed of numerous city-states, known as altepetl, each with its own local governance structures. These city-states were often ruled by their own leaders, who were subordinate to the emperor but held considerable power within their territories. This decentralized form of governance allowed for localized administration, enabling leaders to address the specific needs and challenges of their communities.

Regional leaders, often from noble families, were responsible for collecting tribute, enforcing laws, and maintaining order within their city-states. They were also tasked with mobilizing troops for military campaigns initiated by the emperor. The relationship between the emperor and regional leaders was characterized by a balance of power; while the emperor had the ultimate authority, regional leaders wielded significant influence and autonomy in their domains.

The system of tribute was vital for the empire's economy and military strength. City-states were required to pay tribute in the form of goods, resources, or military support. This system fostered a network of interdependency among the various city-states and the central government, creating a sense of unity while also allowing for regional diversity. The tribute system played a crucial role in the empire's expansion, as it provided the resources necessary for sustaining military campaigns and supporting the lavish lifestyles of the nobility.

The Council of Elders: Decision-Making Processes

In addition to the emperor and regional leaders, the Aztec political system included a council of elders, known as the tlatoque, which played a significant role in decision-making processes. This council was composed of respected individuals from the noble class, chosen for their experience, wisdom, and contributions to society. The council served as advisors to the emperor and regional leaders, ensuring that a broad spectrum of knowledge and perspectives was considered in governance.

The council's influence was particularly pronounced in matters of law and justice. They assisted in establishing legal codes, which were essential for maintaining order in a society characterized by a strict hierarchical structure. The laws often reflected the values and norms of Aztec culture, emphasizing community welfare and the collective good. The council's decisions were respected and often upheld by the emperor, demonstrating the collaborative nature of Aztec governance.

Decision-making within the council was typically consensus-driven, with members engaging in discussions to reach agreements. This process not only enhanced the legitimacy of decisions made but also ensured that various voices within the nobility were heard. In situations of conflict or uncertainty, the council provided a stabilizing force, helping to navigate challenges and maintain the balance of power within the empire.

The council of elders also played a crucial role in the succession process of the tlatoani. When a ruler died or was unable to fulfill his duties, the council would convene to discuss potential successors, often considering both lineage and merit. This practice helped to prevent power struggles and maintain continuity within the leadership of the empire.

Legal System and Social Order

The Aztec political organization was deeply intertwined with its legal system, which was designed to uphold social order and reinforce the hierarchical structure of society. Laws were established to govern various aspects of daily life, including trade, property rights, and social behavior. The legal system was closely associated with the religious beliefs of the Aztecs, as laws were often seen as divinely ordained.

Judicial authority was primarily held by the tlatoani and the council of elders, who adjudicated disputes and enforced laws. However, local leaders within individual city-states also had the authority to enforce laws and settle conflicts. This dual system of justice allowed for flexibility and responsiveness to local issues while maintaining overarching legal standards across the empire.

Penalties for breaking the law varied depending on the severity of the offense. Minor infractions might result in fines or public shaming, while serious crimes, such as theft or murder, could lead to harsher punishments, including death. The legal system emphasized restitution and rehabilitation, reflecting the Aztec belief in community responsibility and social cohesion.

Social order was maintained through a combination of laws, religious practices, and cultural norms. The Aztecs placed a strong emphasis on duty and obligation, which reinforced the hierarchical structure of society. Each class, from nobility to commoners, had specific roles and responsibilities, contributing to the overall functioning of the empire. This system of governance not only ensured stability but also fostered a sense of identity and belonging among the various groups within the empire.

Military Organization and Governance

The military was a crucial component of Aztec governance, serving both as a means of expansion and a tool for maintaining internal order. The emperor, as the supreme commander, led military campaigns but relied on regional leaders to mobilize troops and execute strategies. The military was organized into various units, each with specific roles and responsibilities, reflecting a highly structured approach to warfare.

Aztec warriors, known as eagle warriors and jaguar warriors, were highly trained and held significant prestige in society. Military success was not only vital for expanding territory but also for acquiring tribute and resources from conquered peoples. Victorious campaigns enhanced the emperor's status and solidified the loyalty of regional leaders, creating a cycle of mutual benefit between military success and political power.

Military governance also extended to the treatment of conquered peoples. The Aztecs often allowed subjugated groups to retain a degree of autonomy, provided they paid tribute and acknowledged the emperor's authority. This approach minimized resistance and fostered cooperation, enabling the empire to maintain control over vast territories without constant military enforcement.

In conclusion, the political organization and governance of the Aztec Empire were characterized by a complex interplay between the emperor, regional leaders, and the council of elders. This system not only facilitated effective governance but also reinforced the hierarchical structure that defined Aztec society. Through a combination of military prowess, legal frameworks, and collaborative decision-making, the Aztecs were able to establish and maintain a powerful empire that thrived for centuries.

Economic Systems and Trade

The Aztec Empire, which thrived in central Mexico from the 14th to the 16th century, was not only a political and military powerhouse but also an intricate web of economic systems that facilitated trade and agriculture. The economy was central to the empire's stability and expansion, underpinned by a variety of components that included agriculture, trade networks, and a tribute system. Each of these aspects worked in tandem to support the society's complex hierarchy and way of life.

Agriculture: Farming Techniques and Crops

Agriculture was the backbone of the Aztec economy, providing sustenance for the population and surplus for trade. The Aztecs utilized innovative farming techniques that maximized their agricultural output, given the challenging geography of the Valley of Mexico. The most notable technique was the use of chinampas, or floating gardens, which were essentially small, rectangular areas of fertile arable land constructed on the shallow lake beds in the region.

- Chinampas allowed for year-round farming, significantly increasing crop yields.

- The Aztecs cultivated a variety of crops, including maize (corn), beans, squash, and chilies, which were staples of their diet.

- Other important crops included tomatoes, avocados, and amaranth, which were also integral to their culinary practices.

The chinampas system was labor-intensive and required careful management of water resources, but it resulted in high productivity. Farmers planted multiple crops in succession and employed crop rotation strategies to maintain soil fertility. The Aztecs also practiced terracing on hillsides, which helped prevent soil erosion and maximize the use of land for agriculture.

The surplus production not only fed the population but also allowed for trade with neighboring city-states and regions. The integration of agriculture into the economy set the stage for the development of a complex trade network, which would further enrich the Aztec society.

Trade Networks: Markets and Commerce

The Aztec economy was characterized by a sophisticated network of trade that facilitated the exchange of goods and services across vast distances. Markets were central to this system, with the most prominent being the Tianguis in Tenochtitlan, the capital of the empire. These markets operated on a cyclical basis, often daily or weekly, and were bustling hubs of activity where merchants, artisans, and commoners engaged in trade.

- Goods exchanged included agricultural products, textiles, pottery, and crafted items such as jewelry and tools.

- Merchants played a vital role in the economy, with pochteca being the elite class of merchants who traveled long distances to trade.

- Trade routes extended from the Gulf Coast to the Pacific Coast, connecting the Aztecs with other cultures and facilitating the exchange of exotic goods like cacao, which was highly valued.

The merchants not only engaged in the sale of goods but also acted as diplomats and spies, gathering information about other cultures and potential threats to the empire. This dual role illustrated the significance of trade in both economic and political spheres. The Aztec economy was thus not merely about goods but also about relationships and power dynamics.

Additionally, the use of cacao beans as a form of currency further emphasized the importance of trade. Cacao beans were highly prized not just for their use in beverages but also as a medium of exchange, allowing for transactions to take place without the direct exchange of goods. This system provided flexibility and facilitated long-distance trade.

Tribute System: Contributions and Benefits

The tribute system was a fundamental aspect of the Aztec economy, serving as a means for the empire to exert control over conquered territories. When the Aztecs expanded their influence, they required the subjugated city-states to pay tribute in the form of goods, resources, and labor. This system was not merely exploitative; it also established a framework of mutual benefits and obligations.

- Tribute payments included agricultural products, textiles, precious metals, and even human captives for religious sacrifices.

- The tribute system helped ensure a steady flow of resources to Tenochtitlan, supporting the population and the elite class.

- Tribute was collected annually, and the amounts were determined by the wealth and productivity of the tributary regions.

While the tribute system was a means of asserting dominance, it also fostered a sense of interdependence among the various city-states. The Aztecs provided protection and political stability in return for these tributes, which helped integrate diverse cultures into the empire. The tribute system thus not only enriched the Aztec economy but also reinforced social hierarchies and political structures.

Moreover, the tribute system allowed the ruling class to maintain their lavish lifestyles. The elite lived in opulence, supported by the wealth generated through tribute and trade, which further entrenched the social stratification within Aztec society.

Summary of Economic Systems

The convergence of agriculture, trade, and the tribute system created a robust economic framework that sustained the Aztec Empire during its peak. The innovative agricultural practices ensured food security and surplus, while the trade networks facilitated economic interactions with other cultures, enriching Aztec society. The tribute system tied the empire together, providing the resources necessary for the ruling class and ensuring the loyalty of conquered peoples.

In summary, the economic systems of the Aztecs were complex and multifaceted, reflecting their ingenuity and adaptability in a challenging environment. This intricate web of agriculture, trade, and tribute played a crucial role in the rise and maintenance of one of the most formidable empires in Mesoamerican history.

| Economic Aspects | Description |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | Use of chinampas and terracing to maximize crop yields. |

| Trade Networks | Extensive markets and merchant classes facilitating commerce. |

| Tribute System | Contributions from conquered city-states supporting the empire. |