Aztec Education: The Calmecac and Telpochcalli Schools

The education system of the Aztecs offers a fascinating glimpse into the intricate societal structures of one of the most advanced civilizations in pre-Columbian America. Unlike many ancient societies that reserved education for the elite, the Aztec approach was remarkably inclusive, providing distinct educational paths for both nobles and commoners. This dual system was not merely a means of imparting knowledge but a fundamental pillar that upheld the cultural, religious, and social fabric of Aztec life.

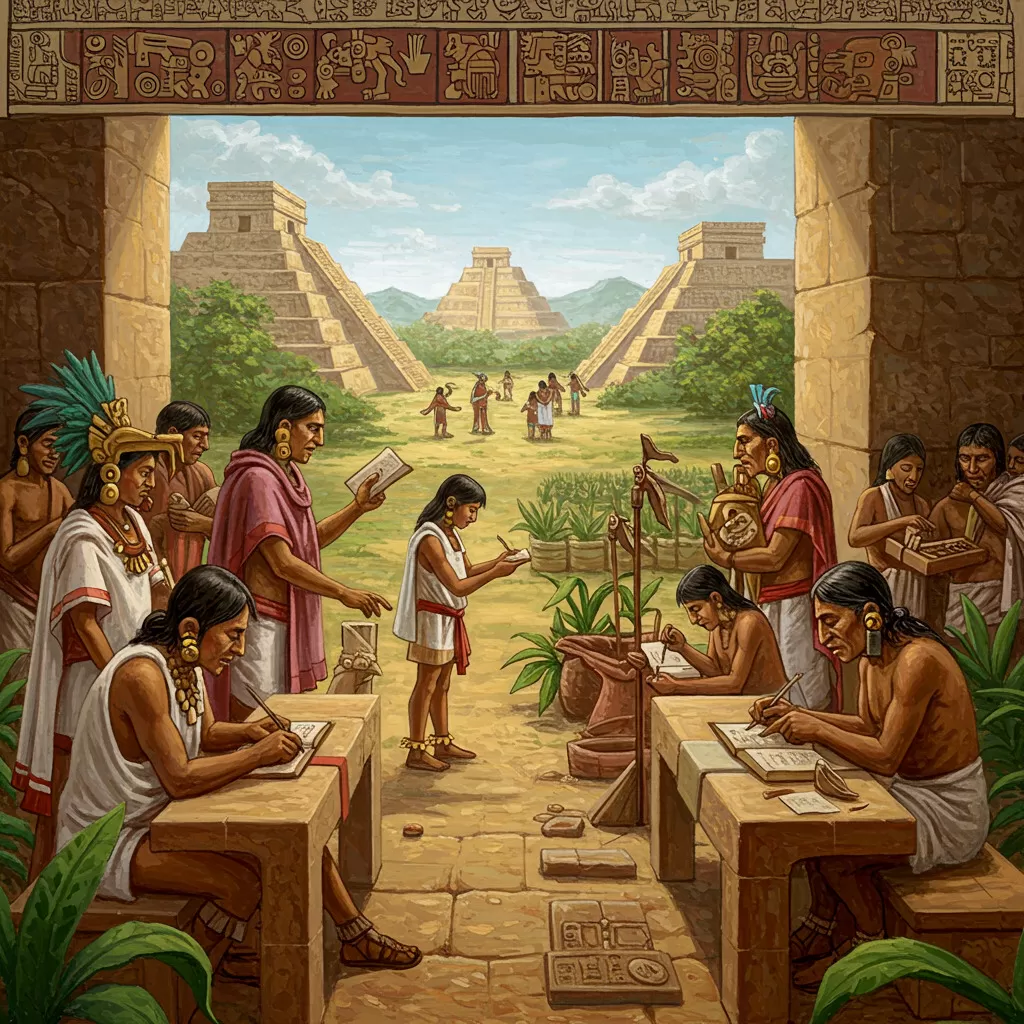

At the heart of Aztec education were two main institutions: the Calmecac and the Telpochcalli. The Calmecac served as the prestigious school for the nobility, focusing on spiritual and leadership training, while the Telpochcalli catered to the common populace, emphasizing practical skills and community values. Together, these schools shaped the identities and capabilities of the Aztec youth, ensuring that each generation was equipped to contribute meaningfully to their society.

Understanding Aztec Education System

The education system of the Aztec civilization, which flourished in Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries, was a complex structure deeply intertwined with the cultural, religious, and social fabric of their society. Unlike many contemporary educational systems that prioritize formal schooling, the Aztec approach was holistic, aiming not only to impart knowledge but also to instill values and skills necessary for community life. Education in Aztec society was divided mainly into two distinct types of institutions—the Calmecac for the nobility and the Telpochcalli for commoners—each serving specific societal roles and functions. Understanding the historical context and role of education in Aztec society provides insight into how this ancient civilization maintained its social order and cultural identity.

Historical Context of Aztec Education

The roots of the Aztec education system can be traced back to earlier Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Olmecs, Teotihuacan, and the Toltecs. These cultures laid the groundwork for the educational practices that the Aztecs would later adopt and adapt. By the time the Aztecs established their empire in the early 14th century, they had developed a unique educational framework that emphasized moral and civic instruction alongside practical skills.

Education in the Aztec Empire was largely a response to its needs as a growing civilization. As the empire expanded, the demand for educated individuals in various fields—such as administration, military, and religious leadership—became crucial. The Aztecs recognized that a well-educated populace was essential for the sustainability of their empire. Consequently, education became a state-sponsored endeavor, reflecting the values and priorities of the society.

Furthermore, the Aztec education system was not merely a tool for personal advancement; it was also a means of social cohesion. The Aztecs believed that knowledge was a communal asset and that sharing it among members of society strengthened their cultural identity. Education was seen as a public duty, with the community playing an essential role in the upbringing and education of its youth.

Role of Education in Aztec Society

In Aztec society, education served multiple roles, acting as a vehicle for socialization, cultural transmission, and the reinforcement of societal norms. From an early age, children were taught the values and beliefs of their community, which included respect for the gods, adherence to social hierarchies, and the importance of civic duty. This early socialization was crucial in preparing them for their roles as future members of Aztec society.

The education system also played a vital role in upholding the religious beliefs of the Aztecs. The teachings in both Calmecac and Telpochcalli schools were infused with religious instruction. Students learned not only about the pantheon of Aztec gods but also about rituals, ceremonies, and the importance of maintaining the cosmic order through their actions. This religious aspect served to reinforce the idea that education was not just about acquiring knowledge but also about fulfilling one's spiritual and social responsibilities.

Moreover, education was a means of social mobility, albeit limited. While the Calmecac primarily served the elite, it provided opportunities for those of noble birth to gain knowledge that would prepare them for leadership roles. For commoners, the Telpochcalli offered practical skills that could improve their status within their communities. This system allowed for a certain degree of movement within the social hierarchy, although it remained largely rigid, reflecting the overall stratification of Aztec society.

In summary, the education system of the Aztecs was multifaceted and deeply embedded in the historical and cultural context of their civilization. It was a fundamental aspect of their society that contributed to the cohesion and continuity of their cultural identity, preparing individuals for their roles within the broader social structure.

The Calmecac School: Elite Education for Nobles

The Calmecac represented the pinnacle of education in the Aztec civilization, designed specifically for the noble class. This elite institution was not merely a place for academic learning; it was a comprehensive system that prepared young Aztecs for leadership roles, priesthood, and the responsibilities that came with their noble lineage. The significance of the Calmecac extended beyond individual education; it was a fundamental component in maintaining the social structure and religious practices of the Aztec society.

Curriculum and Subjects Taught

The curriculum at the Calmecac was extensive and rigorous, reflecting the high expectations placed on its students. Education was multifaceted, combining practical skills with theoretical knowledge. The subjects taught included:

- Religion and Rituals: Students were educated in the religious texts and practices essential to Aztec spirituality.

- History: Understanding the past was crucial for future leaders, as it informed their decisions and governance.

- Philosophy: Students engaged in discussions about ethics, governance, and the nature of the universe.

- Mathematics and Astronomy: Knowledge of astronomy was vital for agricultural planning and religious ceremonies.

- Art and Music: Cultural education included the study of traditional arts, music, and dance, which were integral to religious and social events.

- Military Strategy: As many graduates would become leaders, they were trained in the arts of warfare and tactics.

This diverse curriculum ensured that students were well-rounded, capable of handling the complexities of leadership and religious duties. The Calmecac not only aimed to impart knowledge but also sought to instill values such as piety, honor, and a sense of duty to the community.

Training for Priesthood and Leadership

One of the primary functions of the Calmecac was to prepare students for roles as priests and leaders within the empire. This training was both theoretical and practical. Students spent considerable time learning about the intricate rituals associated with Aztec religion, including sacrifices, offerings, and ceremonies that were pivotal in appeasing the gods. The role of a priest was not only spiritual but also political, as they held significant influence over the populace and the ruling elite.

Leadership training encompassed understanding the responsibilities that came with power, including governance, diplomacy, and military leadership. Students were taught to be just and wise rulers, capable of making decisions that would benefit their people and maintain the stability of the empire. They learned to navigate the intricate social hierarchies and political landscapes of the Aztec world, preparing them for the challenges they would face as leaders.

Moreover, the Calmecac emphasized the importance of lineage and heritage. Students were often from noble families, and their education was a means of continuing their family's legacy and influence within Aztec society. This connection to ancestry reinforced the idea that education was not merely for personal advancement but also for the greater good of the community and the empire.

Cultural and Religious Significance

The Calmecac held profound cultural and religious significance within Aztec society. As a center of learning for the elite, it was instrumental in the preservation and propagation of Aztec culture and religious beliefs. The education received at the Calmecac shaped the values and ideologies of the future leaders and priests, who would go on to influence the broader society.

Religious education was paramount at the Calmecac, as students were taught to understand the complex pantheon of gods and the importance of rituals. The Aztec worldview was deeply embedded in their education, with a strong emphasis on the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, which was reflected in their rituals and societal practices. Students learned that their roles as priests and leaders were not just positions of power but also responsibilities to uphold the cosmic order and ensure the favor of the gods.

The Calmecac also served as a cultural hub, where traditional stories, songs, and artistic expressions were taught and preserved. This emphasis on culture was crucial for maintaining a cohesive identity among the Aztec people. The education provided at the Calmecac ensured that future generations would carry forward the rich heritage of the Aztec civilization, thus reinforcing the importance of cultural continuity in a society that valued its history and traditions.

In summary, the Calmecac was more than just an educational institution; it was a vital component of the Aztec social structure that shaped the leaders and priests of the empire. Through its rigorous curriculum, the Calmecac prepared young nobles for their future roles while instilling in them a sense of duty to their community and culture. The religious and cultural significance of this school cannot be overstated, as it played a crucial role in the preservation of Aztec identity and values.

The Telpochcalli School: Education for Commoners

The Telpochcalli, one of the two main types of educational institutions in the Aztec Empire, played a fundamental role in shaping the lives of commoners and ensuring that the societal fabric of the empire remained intact. While the Calmecac served the elite, the Telpochcalli focused on the education of common children, primarily aimed at preparing them for their roles in society. This institution was not merely a school in the modern sense but a critical component of the community that instilled values, skills, and knowledge essential for the everyday functioning of Aztec life.

Curriculum and Practical Skills

The curriculum at Telpochcalli was designed to impart practical skills and knowledge that were directly applicable to the daily lives of the students. Unlike the Calmecac, where the education was theoretical and elite, Telpochcalli focused on the realities of life for commoners. The subjects taught included agricultural practices, craftsmanship, trade skills, and physical training, all aimed at making the students productive members of their communities.

- Agricultural Education: Students learned the importance of maize cultivation, irrigation techniques, and seasonal planting. This knowledge was vital for sustaining the community and ensuring food security.

- Craftsmanship: Skills in pottery, weaving, and tool-making were emphasized, with students often engaging in hands-on projects that reinforced their learning.

- Trade Skills: For those inclined towards commerce, understanding the marketplace, bartering, and basic accounting were part of the education, preparing them for roles as merchants or craftsmen.

- Physical Training: Emphasis was placed on physical fitness, as many students would participate in sports and games that were crucial for community events and warfare.

The practical nature of the curriculum ensured that students were not just passive recipients of knowledge but active participants in their education. The hands-on approach to learning fostered critical thinking and problem-solving skills, essential for survival in the challenging environment of the Aztec Empire.

Preparing Youth for Workforce and Society

The Telpochcalli was also instrumental in preparing young Aztecs for their future roles in the workforce and society at large. The education provided was not merely about acquiring skills; it was about integrating the youth into the social fabric of the empire. The school emphasized the importance of community service, social responsibility, and the values of cooperation and respect.

Students were taught to take pride in their work and to understand their contributions to society's well-being. This instilled a sense of identity and belonging, essential for the cohesion of the Aztec community. The education at Telpochcalli was thus a means of socialization, where children learned not just about their immediate responsibilities but also about their roles within the larger context of the empire.

Moreover, the Telpochcalli prepared students for the various roles they would assume as adults. Young men were groomed for positions as farmers, artisans, and warriors, while young women were educated in domestic skills, preparing them for their future roles as mothers and caretakers. This gender-segregated approach ensured that both boys and girls received the training necessary to fulfill their societal obligations, albeit in different spheres.

Community and Social Impact of Telpochcalli

The impact of the Telpochcalli extended beyond the individual students; it resonated throughout the entire community. By educating the youth, the Telpochcalli played a vital role in maintaining the social order and cultural continuity of the Aztec Empire. The school served as a hub for community interaction and engagement, where families could gather for events, celebrations, and festivals.

Furthermore, the Telpochcalli fostered a sense of unity among the common people. By providing a shared education experience, the school helped to bridge the gap between different social classes, even if only to a limited extent. The commoners who attended Telpochcalli were instilled with a sense of pride in their heritage and a respect for their community's traditions, which was crucial in an empire where social hierarchies were deeply entrenched.

The graduates of Telpochcalli often took on leadership roles within their communities, becoming respected figures who contributed to the governance and welfare of their towns and villages. This process of community leadership ensured that the values taught in school were carried into adulthood, perpetuating a cycle of responsible citizenship and civic duty.

In addition to fostering local leadership, the Telpochcalli also contributed to the overall stability of the Aztec Empire. By equipping commoners with necessary skills and knowledge, the school helped to create a workforce capable of sustaining the empire's economy. This was particularly important as the Aztec Empire expanded, requiring skilled laborers and artisans to support its growth and development.

Conclusion

In summary, the Telpochcalli was more than just an educational institution for commoners; it was a foundational pillar of Aztec society. By providing practical education and instilling social values, it prepared youth for their roles in the workforce and within their communities. The impact of the Telpochcalli was profound, shaping not only the individual lives of students but also the very fabric of Aztec civilization. Through its emphasis on community, responsibility, and practical skills, the Telpochcalli contributed significantly to the stability and continuity of the Aztec Empire.