Aztec Economy: Trade, Tribute, and Agriculture

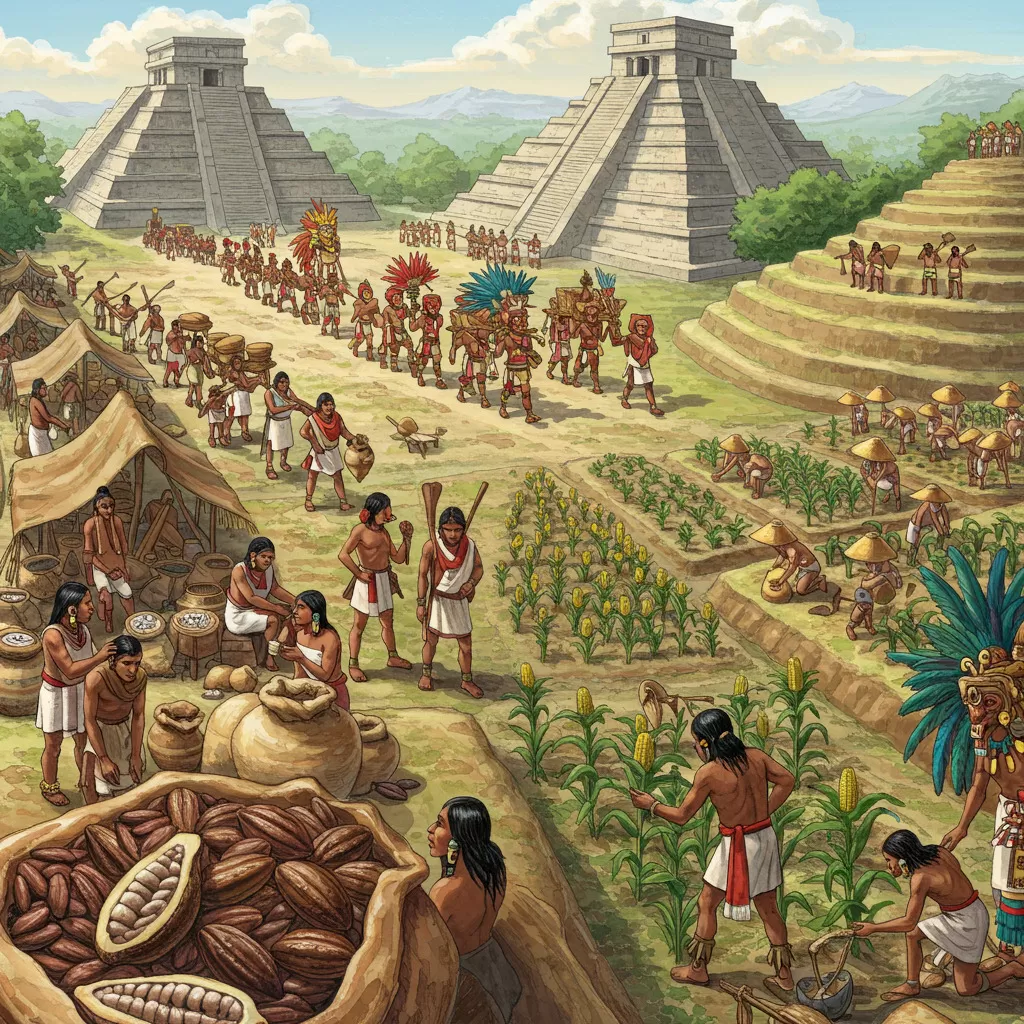

The Aztec Empire, one of the most sophisticated civilizations in Mesoamerica, had a complex economy that played a crucial role in its development and longevity. Understanding the intricacies of Aztec economic practices reveals not only their agricultural prowess but also the vibrant trade networks and tribute systems that underpinned their society. From bustling marketplaces to the tribute collected from conquered territories, the economic strategies of the Aztecs were essential in sustaining their vast empire and supporting their rich cultural achievements.

This article delves into the key components of the Aztec economy, exploring the historical context and the various elements that contributed to its functionality. We will examine trade routes that connected distant regions, the goods that flowed through these networks, and the significance of agriculture as the backbone of Aztec life. By analyzing these aspects, we can gain a deeper appreciation for how the Aztecs managed their resources and established a thriving civilization in a challenging environment.

Overview of the Aztec Economy

The Aztec economy was a complex and sophisticated system that played a crucial role in the development and sustainability of one of the most powerful civilizations in Mesoamerica. Emerging in the 14th century, the Aztec Empire, also known as the Mexica, was characterized by its remarkable ability to integrate diverse economic practices, ranging from agriculture and tribute collection to extensive trade networks. Understanding the historical context and development of the Aztec economy, as well as its structure and functionality, is essential to grasp the dynamics that fueled the empire's growth and influence.

Historical Context and Development

The rise of the Aztec economy can be traced back to the early migration of the Mexica people, who settled in the Valley of Mexico in the early 14th century. Initially, they were a nomadic tribe, but as they established themselves, they adapted agricultural practices learned from neighboring cultures, particularly the Toltecs and the Teotihuacanos. This agricultural foundation was vital for the Mexica, as it allowed them to transition from a nomadic lifestyle to a settled society, leading to the establishment of Tenochtitlán in 1325.

By the time the Aztecs began to expand their territory, they had developed a sophisticated agricultural system that utilized chinampas—floating gardens built on the shallow lake beds of the Valley of Mexico. This innovative technique allowed for the cultivation of multiple crops throughout the year, resulting in surplus production that supported a growing population and facilitated trade. The abundance of resources attracted people from surrounding regions, further enhancing the economic landscape of the empire.

As the Aztecs expanded their influence through military conquests, they incorporated various city-states into their empire, each contributing to the overall economy. The tribute system became a cornerstone of the Aztec economy, where conquered peoples were required to pay tribute in the form of goods, labor, and resources. This system not only enriched the empire but also established a complex network of economic interdependence among the various regions under Aztec control.

Economic Structure and Functionality

The economic structure of the Aztec Empire was multifaceted, encompassing agriculture, trade, tribute, and crafts. Each component played a vital role in ensuring the empire's stability and growth. The integration of these elements allowed the Aztecs to maintain a robust economy that could support a large population and an expanding military.

Agriculture was the backbone of the Aztec economy. The innovative use of chinampas enabled the cultivation of staple crops such as maize, beans, and squash, which were essential for sustaining the population. Additionally, the Aztecs grew other crops like tomatoes, avocados, and chili peppers, which not only provided sustenance but also contributed to the culture and cuisine of the empire.

Trade was another critical component of the Aztec economy. The empire established extensive trade networks that connected various regions, allowing for the exchange of goods and resources. Markets were bustling centers of economic activity, where merchants sold everything from food to textiles and luxury items. The most famous marketplace was Tlatelolco, where thousands of people would gather daily to conduct trade. The Aztecs used a system of barter, but they also developed a form of currency using cacao beans and cloth, which facilitated transactions and improved economic efficiency.

The tribute system was essential for maintaining the power and wealth of the Aztec state. Tribute was collected from conquered regions and varied significantly, encompassing agricultural products, textiles, precious metals, and even human labor. This system not only provided the empire with the resources needed to support its military and administrative functions but also reinforced the social hierarchy, as those who paid tribute were often at the mercy of the ruling class.

In conclusion, the overview of the Aztec economy reveals a dynamic and interconnected system that was instrumental in the rise of one of Mesoamerica's most influential civilizations. The historical context underscores the importance of agriculture, trade, and tribute in shaping the economic landscape, allowing the Aztecs to thrive in a competitive environment. This multifaceted economic structure not only provided the foundation for the empire's expansion but also established a legacy that would influence subsequent civilizations in the region.

Trade in the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, which thrived in central Mexico from the 14th to the early 16th century, boasted a complex and sophisticated trade system. This trade network was vital for the empire’s economic prosperity, facilitating the exchange of a variety of goods and commodities, which in turn enabled the Aztecs to maintain power and influence over a vast territory. Understanding the intricacies of trade in the Aztec Empire illuminates the ways in which commerce shaped their society, culture, and economy.

Trade Routes and Networks

Trade routes in the Aztec Empire were extensive and well-organized, connecting different regions and facilitating the movement of goods. The core of the empire was Tenochtitlán, located on an island in Lake Texcoco, which served as a central hub for trade activity. From here, a network of roads and waterways radiated outward, linking diverse communities and regions.

- Road Systems: The Aztecs constructed a network of causeways and roads that connected Tenochtitlán with surrounding areas. These roads facilitated the movement of merchants and goods, ensuring that trade flourished.

- Waterways: The lakes and canals surrounding Tenochtitlán were used extensively for transport. Canoes and barges carried goods to and from the city, allowing for efficient trade across the region.

- Interregional Trade: The Aztecs engaged in trade not only within their own empire but also with neighboring cultures. This interregional trade involved the exchange of local products for luxury items, creating a vibrant economic landscape.

The significance of these trade routes cannot be overstated. The Aztec economy depended heavily on the efficient transportation of goods, and the infrastructure they developed allowed for the quick movement of both resources and people. This network also contributed to the cultural exchange between different regions, spreading ideas and innovations throughout the empire.

Key Goods and Commodities

The Aztec economy was characterized by a diverse array of goods and commodities that were traded both locally and regionally. These goods can be broadly categorized into several groups, each with its own significance and value.

- Food Products: Agriculture played a critical role in the Aztec economy. Essential food items such as maize, beans, and squash were staples, and surplus production allowed for trade with other regions. Additionally, luxury foods like chocolate and spices were highly sought after.

- Textiles: The Aztecs produced intricate textiles made from cotton and other fibers, which were not only used for clothing but also for trade. These textiles were often dyed in vibrant colors and featured elaborate designs.

- Precious Materials: Gold, silver, and jade were highly valued in Aztec society and were often used as currency or for decorative purposes. The trade of these materials contributed significantly to the wealth of merchants and the empire as a whole.

- Crafted Goods: Artisans produced a range of crafted goods, including pottery, tools, and ceremonial items. These products were often traded at markets and were integral to daily life and rituals.

The diversity of goods available for trade reflected the rich agricultural and artisanal capabilities of the Aztecs. The ability to produce a wide variety of items not only supported local consumption but also established the Aztecs as significant players in regional trade networks.

Role of Markets and Merchants

Markets were central to the Aztec economy, serving as focal points for trade and commerce. The largest and most famous market was the Tlatelolco market, located in the twin city of Tenochtitlán. This market was a bustling hub where merchants from various regions gathered to buy and sell goods.

- Organization of Markets: Markets were organized in a systematic way, often taking place on specific days of the week. Vendors would set up stalls, and the atmosphere was vibrant, with sounds of haggling and the smell of food wafting through the air.

- Types of Merchants: Merchants in the Aztec Empire held a unique position. There were two main types: the pochteca, who were long-distance traders, and local merchants who focused on smaller-scale trade. Pochteca traveled far and wide, often bringing back exotic goods, while local merchants catered to the immediate needs of the community.

- Currency and Barter: While commodities were exchanged, the Aztecs also utilized a system of currency, primarily based on cacao beans and occasionally gold dust. This system allowed for more complex transactions and facilitated trade across various regions.

The role of markets and merchants in the Aztec economy cannot be underestimated. They were crucial in promoting trade, facilitating cultural exchange, and connecting diverse communities. The vibrant marketplace atmosphere exemplified the dynamic nature of the Aztec economy and its reliance on commerce.

In conclusion, trade in the Aztec Empire was a multifaceted and essential component of its economy. The well-established trade routes and networks, the diverse range of goods exchanged, and the crucial role of markets and merchants all contributed to the empire's prosperity and cultural richness. Through trade, the Aztecs not only acquired the resources they needed for daily life but also established their influence over a vast territory, solidifying their place in history as one of the most significant civilizations in pre-Columbian America.

Tribute System of the Aztecs

The tribute system of the Aztec Empire was a fundamental aspect of its economic and political structure. It was not merely a means of generating wealth; it was also a method of maintaining control over vast territories and diverse populations. The tribute system ensured that the empire could sustain its military, support its ruling class, and fund large-scale public works. This section will explore the purpose and importance of tribute, the types of tribute collected, and the impact of this system on economic stability and power dynamics.

Purpose and Importance of Tribute

The primary purpose of the tribute system was to establish and maintain the power of the Aztec rulers. The Aztecs, who referred to themselves as the Mexica, expanded their territory through a combination of military conquest and strategic alliances. Once a region was conquered, it was required to pay tribute to the Aztec Empire. This tribute was essential for several reasons:

- Economic Resource: The tribute provided a steady flow of goods, resources, and wealth to the empire, allowing it to thrive economically. This influx of goods was critical for supporting the urban elite and funding public works.

- Political Control: By enforcing tribute demands, the Aztecs exerted political control over their tributary states. Failure to pay tribute could result in military action, allowing the Aztecs to maintain dominance over their territories.

- Cultural Integration: The tribute system was also a means of integrating diverse cultures within the empire. It imposed a unifying economic structure that encouraged the exchange of goods and ideas among different peoples.

Moreover, tribute was seen as a form of reciprocity. In return for the goods and services provided by the tributary states, the Aztec Empire offered protection, trade opportunities, and a sense of belonging to a larger political entity. This complex relationship helped to foster loyalty among the conquered peoples.

Types of Tribute Collected

The types of tribute collected by the Aztecs were diverse and varied significantly based on the resources available in each tributary region. Each tribute state was assessed based on its economic capacity and geographical advantages. The main categories of tribute included:

- Agricultural Products: These included staples such as maize, beans, and squash, as well as luxury items like cacao, which was highly valued in Aztec society. Agricultural tribute was crucial for feeding the population of Tenochtitlan.

- Fish and Marine Resources: Coastal regions were required to deliver fish, salt, and other marine products. These resources were essential to the Aztec diet and trade.

- Textiles and Craft Goods: Regions known for weaving and craftsmanship would send textiles, pottery, and other crafted goods as tribute. These items were not only valuable for trade but also for the elite's consumption.

- Precious Metals and Stones: Some regions were rich in minerals, leading to the collection of gold, silver, and precious stones. Such tributes were particularly important for the elite and religious ceremonies.

The tribute was often collected in a systematic manner, with officials sent to oversee the collection process. This included a detailed accounting of what was owed and ensuring compliance from the tributary states. The tribute was a formalized system that reinforced the power dynamics between the Aztec rulers and the conquered peoples.

Impact on Economic Stability and Power Dynamics

The tribute system had profound implications for the economic stability of the Aztec Empire. The steady influx of goods allowed for a thriving urban economy, particularly in the capital, Tenochtitlan. This city became a bustling center of trade and commerce, attracting merchants from across Mesoamerica. The wealth generated by the tribute system facilitated the development of infrastructure, including temples, roads, and canals, which further enhanced the empire's economic capabilities.

However, the tribute system also created significant power dynamics that could lead to instability. While it served to enrich the Aztec elite, it often burdened the common people in the tributary states. High tribute demands could lead to resentment and rebellion. Several notable rebellions occurred during the height of the Aztec Empire, driven in part by the oppressive nature of the tribute system. The famous Tlaxcalans, for example, resisted Aztec domination and ultimately played a pivotal role in the Spanish conquest of the empire.

Moreover, the reliance on tribute to sustain the economy made the Aztec Empire vulnerable to disruptions. Natural disasters, such as droughts or floods, could impact agricultural output, leading to difficulties in meeting tribute demands. Such situations could result in weakened political control and economic instability.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Economic Growth | Enhanced urban economy and development of Tenochtitlan as a trade hub. |

| Political Control | Maintained dominance over tributary states through economic dependence. |

| Social Tensions | Created resentment among common people leading to potential uprisings. |

| Vulnerability | Economy susceptible to disruptions due to environmental factors. |

In summary, the tribute system was a cornerstone of the Aztec economy, serving multiple functions that reinforced the empire's power and stability. While it fostered economic growth and political control, it also laid the groundwork for social tensions and vulnerabilities that would eventually contribute to the empire's decline. Understanding the tribute system provides crucial insights into the complexities of Aztec society and its economic mechanisms.

Agriculture in the Aztec Civilization

The Aztec civilization, flourishing in central Mexico from the 14th to the 16th centuries, is renowned not only for its rich cultural heritage but also for its sophisticated agricultural practices. Agriculture was the backbone of the Aztec economy, providing the necessary food supply that supported their large population and enabled the empire's expansion. This section delves deeply into the various aspects of agriculture in Aztec society, including the farming techniques and innovations they employed, the crops they cultivated, and the critical role agriculture played in their social and economic fabric.

Farming Techniques and Innovations

The Aztecs were innovative farmers, utilizing a combination of techniques that maximized productivity in their diverse environment. One of the most notable methods was the use of chinampas, or floating gardens. These were man-made islands created in the shallow lakes of the Valley of Mexico. The Aztecs constructed chinampas by piling mud and vegetation onto rafts, which were anchored to the lake bed. This ingenious system allowed them to cultivate crops in nutrient-rich soil while also conserving water resources.

Chinampas were incredibly productive, yielding multiple harvests each year. The Aztecs planted various crops in these floating gardens, including maize, beans, squash, and tomatoes. The proximity to water facilitated irrigation, which was essential for maintaining the moisture levels necessary for crop growth. This method not only increased agricultural output but also contributed to the ecological balance of the region by supporting local wildlife and promoting biodiversity.

In addition to chinampas, the Aztecs employed other agricultural techniques such as terracing. On the steeper slopes of mountains, they built terraces that prevented soil erosion and allowed for efficient water management. This technique expanded arable land and was particularly useful for cultivating crops in regions with varying altitudes. The terraces were often constructed with stone walls that held the soil in place, creating flat areas suitable for planting.

Another significant innovation was the use of crop rotation. The Aztecs understood the importance of maintaining soil fertility and practiced rotating different types of crops to prevent depletion of nutrients. For example, they would alternate maize with legumes, which helped restore nitrogen levels in the soil. This practice ensured sustainable agricultural production over the long term.

Crops and Agricultural Products

The Aztec diet was diverse, relying heavily on a variety of crops. Maize was the staple food, forming the basis of their diet and culture. It was consumed in various forms, such as tortillas, tamales, and atole. The significance of maize extended beyond sustenance; it was also central to religious rituals and cultural identity.

Beans were another crucial crop, providing essential proteins that complemented the carbohydrates from maize. The Aztecs cultivated several types of beans, including black, pinto, and kidney beans. Squash, another essential crop, was often grown alongside maize and beans in a system known as the “three sisters,” which promoted mutual growth and pest control.

Other important crops included chiles, which were used to add flavor to dishes, and tomatoes, a fundamental ingredient in many Aztec recipes. The cultivation of cacao also played a significant role in Aztec society, as it was used to produce chocolate, a beverage consumed by the elite and a form of currency.

The Aztecs also engaged in the cultivation of amaranth, a grain that was highly nutritious and could thrive in various conditions. This versatility made amaranth an essential crop, especially during periods of drought. Additionally, the Aztecs harvested various fruits, including avocados, guavas, and prickly pears, which added diversity to their diet and were often used in religious offerings.

Role of Agriculture in Society and Economy

Agriculture was at the heart of Aztec society, influencing not only their economy but also their social structure and cultural practices. The agricultural surplus generated by innovative farming techniques allowed the Aztecs to sustain a large population and develop a complex society. This surplus was vital for the growth of urban centers, such as Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, which became one of the largest cities in the world during its time.

In the economic sphere, agriculture provided the resources necessary for trade. The Aztecs exchanged agricultural products for goods and services, facilitating a vibrant marketplace that was essential for the empire's economy. Markets were organized in various cities, where farmers could sell their surplus produce. These markets became hubs of social interaction and cultural exchange, fostering a sense of community among the population.

The tribute system, which required conquered peoples to provide agricultural goods, also relied heavily on the productivity of Aztec agriculture. This system not only reinforced the power dynamics within the empire but also ensured a steady flow of resources to support the ruling class and military endeavors. The tribute collected from agricultural production was used to fund large-scale projects, including the construction of temples and public works, further enhancing the empire's infrastructure.

Moreover, agriculture played a significant role in religious practices. The Aztecs held numerous agricultural festivals, celebrating the planting and harvesting seasons. These festivals were often marked by rituals that honored deities associated with fertility and agriculture, such as Tlaloc, the rain god, and Xilonen, the goddess of maize. The agricultural calendar dictated much of the Aztec way of life, influencing their social activities and cultural expressions.

The interdependence of agriculture, economy, and society in the Aztec civilization illustrates the importance of this sector in shaping their historical legacy. The agricultural innovations and practices developed by the Aztecs not only sustained their empire but also laid the groundwork for future agricultural systems in the region.

Agricultural Challenges and Adaptations

Despite its successes, Aztec agriculture faced numerous challenges. Environmental factors such as droughts, flooding, and soil degradation threatened agricultural productivity. The Aztecs had to adapt to these challenges through various means, including the construction of irrigation systems and the use of crop diversification to mitigate risks. They also developed a keen understanding of their environment, allowing them to implement practices that would enhance resilience against climatic fluctuations.

During periods of drought, the Aztecs relied on their knowledge of water management and irrigation techniques to sustain crops. They constructed canals and dikes to control water flow and maximize irrigation efficiency. Additionally, the use of chinampas allowed them to cultivate crops even during dry spells, ensuring a continuous food supply.

Soil degradation was another concern, particularly in areas where intensive farming occurred. The Aztecs addressed this issue by practicing crop rotation and intercropping, which helped maintain soil fertility. They understood the importance of nurturing the land to ensure long-term agricultural viability.

In conclusion, agriculture was a cornerstone of the Aztec civilization, shaping its economy, society, and culture. Through innovative techniques and a diverse range of crops, the Aztecs established a robust agricultural system that sustained their empire for centuries. Despite facing environmental challenges, their adaptability and resourcefulness allowed them to thrive in a complex and dynamic landscape.